Thomas Rothwell and the Sydney General Poor Relief Fund

Thomas Rothwell and the Sydney General Poor Relief Fund

The Sydney General Poor Relief Fund (SGPRF) was so named to indicate its purpose. In the period just prior to World War I, it was promoted so that the poor of Sydney might enjoy the sympathy and some financial support of those who were better off. It was, however, a fake charity enriching and providing not for the poor but for an unscrupulous ‘con man’. Not all involved with charity were dishonest. Some who worked as fundraisers for the so-called charity were as duped as the general public.

The Fund was first mentioned in the Sydney Morning Herald 22 November 1909 when a notice, designed to tug on the heartstrings of the sympathetic, was published. It sought gifts and donations towards providing Christmas dinners to the poor and destitute:[1]

And this was followed with an after-Christmas thank-you note for the support the Fund had received, and it hinted about the support it had received for its more general relief program:[2]

Around this time, other concerts were organized by musicians who gave of their time and talents, and the money raised through ticket sales was given to the SGPRF. One such concert was held in the Balmain Town Hall in 1909 under the patronage of the Mayor and Mayoress of Balmain and was organized by Miss B Elvena Hurburgh, a piano teacher,[3] who went on to organize further fundraising concerts for the SGPRF. With increasing attendance, her concert was moved to the Sydney Town Hall with musicians giving of their services for the event. It was so well supported, by both musicians and the public, that it became an ‘annual’ event, providing further funds for the SGPRF up until 1914.[4] Other musicians organized their own concerts for the SGPRF like the piano concert given by Aaron Solomons, with assistance from other musicians, in the YMCA in 1909.[5] Another successful event was the harbour excursion and concert organized by Mrs Haffenden-Smith, assisted by her pupils, which was held aboard the Lady Northcote in 1910.[6]

(more…)Samuel Callaghan (1809-1884) shoes, temperance and benevolence

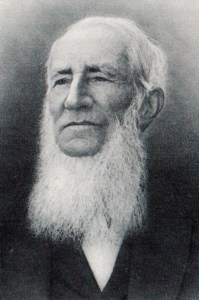

Samuel Callaghan was born in Londonderry, Ireland, on 23 February 1809, or possibly 8 March 1808, as credible sources differ. He was the son of James Callaghan, a shoemaker, and his wife Mary, nee Forsythe.[1] Samuel followed his father’s trade and became a shoemaker, and on 8 March 1829 at Drumachose, Londonderry, Ireland, he married Mary Ann nee May (1811-13 July 1894).[2] Nine years later, on 19 October 1838, Samuel and his wife, plus their four children James (1829-1910), Robert (1832-1874), Jane (1833-1920) and John (1837 -1915), embarked on the ‘Susan’ leaving Londonderry and arriving in the colony of NSW on 5 March 1839[3] as part of a shipload of 261 government sponsored emigrants.[4]

Church

About 1828 and when in Ireland, Callaghan had become a member of the Wesleyan Church, and upon arrival in New South Wales, he connected with the Wesleyan Church in Macquarie Street, Sydney, and later became a teacher in the Druitt Street Wesleyan Sunday School. After a few years, he moved to the Chippendale circuit and, with others, established a Sunday School there. Later, he connected with the York Street Church and subsequently with the Burke Street circuits. For about eight years, from around 1872, he was superintendent of the Hay Street Wesleyan Sunday School and retired from this work in about 1880 due to poor health.

The Sydney Wesleyan Sunday School Union, of which Samuel was a member from at least 1846, reported in that same year that their student numbers had increased by 311 to a total of 978, with an increase in teachers of 36; this brought the total number of teachers to 106.[5] Sunday School teaching, to which Callaghan devoted approximately 40 years of his life, would prove to be a significant source of growth for the Wesleyan Church. Around 1851, he became a committee member of the Wesleyan Mission Society NSW Auxiliary, an organization dedicated to supporting the outreach of the Wesleyan Church through Missions.[6]

At his death on 29 August 1884, Callaghan had been associated with various efforts of the Wesleyan Church in the colony of NSW for a period of 45 years, and for about 11 years in Ireland prior to coming to Australia.[7] His family maintained an active involvement in Wesleyan/Methodism well into the 20th Century, and one of his grandsons, Robert Samuel Callaghan, was hailed by The Methodist as ‘a prince and a great man’ of Australian Methodism.[8]

(more…)Walter Vincent: Funds, Fatigue and Fraud – an aspect of charity in nineteenth-century NSW

Walter Vincent alias Brown was a member of the opportunistic profession of the sweet-talking donation fraudster. He presented himself as a genuine collector of subscriptions for various charities, but he was not.

Obtaining funding for the work of the various nineteenth-century philanthropic organisations was always a challenge. There was little government financial assistance available, and the various charitable organisations were dependent upon the generosity of the public for financial support. To gain that support, the many charities that wished to collect money from the public engaged in a number of activities and strategies. Prominent among their activities was the public annual meeting, often chaired by a socially important person, where the activities of the organisation were reported and supportive resolutions passed. At the meeting, someone, usually the committee secretary, would read a report detailing what had been achieved in the past year, often giving encouraging examples of success and underlining the difficulty of the task which the charity had undertaken. Such reporting made the committee that ran the charity accountable to the public and to its subscribers. It also showed what had been achieved through public financial support, educated the community on the continuing need for the charity, and gave hope for success in the future, so that there might be continued interest and increased financial support given by individuals. These meetings were often widely reported in detail by the press, which devoted considerable space to them.

During the 1890s through to the first decade of the 1900s, the colonies of Australia experienced a severe economic depression. Businesses reported a slowness in trade, a drop in profits, the need to shed workers and in the case of many, through indebtedness and an inability to service loans, to declare bankruptcy. On the personal front, and as a result of reduced income, this meant less food on the table and less access to medical assistance if needed. There was an increase in unemployment as businesses, both large and small, sought to reduce expenditure in an attempt to survive the times.

(more…)William Henry Millwood Haselhurst (1842-1917) gold miner

William Henry Millwood Haselhurst (1842-1917) was the son of Samuel Haselhurst (1795-1858) a gold miner[1] and Elizabeth Ann nee Atkins, then later Hosken, (1810-1890).[2] He was born at Lane Cove River near Sydney in February 1842, and at three years of age he was taken by his parents to Adelaide and then to the Burra Burra Copper mines in South Australia.

In 1852, the family moved to Bendigo, Victoria, where Samuel was involved in gold mining. This experience introduced William to what was to be his main interest in life – gold. He told the following story about himself:

In 1853, I was a boy of eleven years of age, living at Mount Korong, near what is now known as Wedderburn. One morning I was washing dirt in a tub at an old mullock heap in the eternal quest for gold. I might mention that the tub was made of an old flour barrel, and that our flour was imported from Valparaiso. My young brother was working with me, and we were intently engaged in our work when a company of the licence-hunters came along. The official stood and looked at me, then the sergeant gave the order. “March him off.” So I was marched off to the camp and charged with not having a licence. They evidently thought me trustworthy, because they allowed me outside the tent. For my dinner they gave me dumpling and sugar. In the afternoon my father called to interview the commissioner, who concluded I was too young to be compelled to have a licence, I was let off. Young as I was then, I remember that I fossicked out of a drive at the bottom of an abandoned shaft a nugget that weighed 3 oz. So perhaps the sergeant was right in thinking I should have had a licence.[3]

(more…)George William Barker (1826-1897) Wesleyan, Baker and ‘no idler in his Lord’s vineyard’

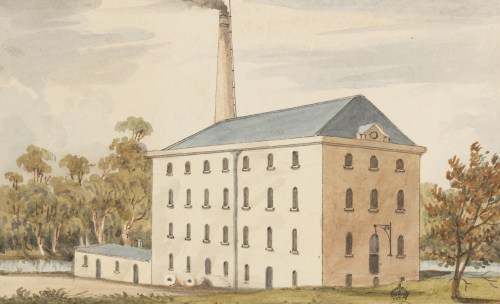

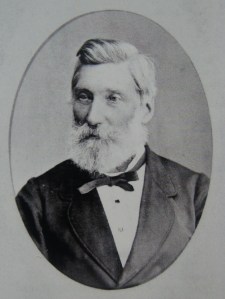

George William Barker was born in London on 5 July 1826, the son of George Barker (1803-1878) a musical instrument maker and Sarah Ann Craddock (1804-1887).[1] He came to Sydney on the Spartan with his parents, three sisters, Mary Ann, Sarah and Emma, and his younger brother, William. They arrived on 31 January 1838 after a voyage of some five months.[2] George’s uncles, Thomas (1799-1875) and James (1797–1861) Barker had arrived in the colony in 1822, some 15 years before, with Thomas[3] working as a clerk for John Dickson (1744-1843) a flour miller.[4] George was educated at Dr Fullerton’s School, Windsor, the King’s School, Parramatta, and the Grammar School Sydney.

Initial Business Involvement

After school and for some time, George partnered with his father as a grocer and corn dealer, in George Street Parramatta. In December 1847,[5] the public was advised that George was leaving the partnership.[6] So it was that in 1848, attracted by the business opportunities afforded by the development of Port Phillip and perhaps with a sense of adventure, he travelled overland with several friends for some 8 weeks to the Geelong area where he settled and ‘found a position in a store’.[7]

Family and Faith

It would appear that the move to the Geelong area was quickly crowned with success for George was soon able to marry. A friend recalled that “soon after a certain young lady went down to Melbourne from Parramatta, and Master George obtaining a week’s holiday started also for Melbourne, and at the end of the week returned with Mrs. Barker.”[8] In 1849 in Melbourne, George had married Eliza Hunt the daughter of Richard Hunt, a saddler and Lydia nee Barber.[9] Eliza was born in the Parramatta area and was known to George before travelling to Geelong.[10] They were to have six children: Sarah Elizabeth (1850-1851), Thomas Richard (1854-1860), Edwin George (1856-1918), Emily Eliza (1858-1931), Alice Maude (1863-1945) and Florence (1865-1867).

The Hunt family were involved with the Parramatta Wesleyan church and while the Barkers were involved with the Presbyterian Church in Parramatta,[11] George is only ever found associated with the Wesleyan Church. According to the Rev Joseph Oram, Barker became a member of the Wesleyan Church at Parramatta before he went to Geelong having been converted ‘during a religious festival when the Rev’s John Watsford and William Moore were brought to Christ’.[12] Watsford was converted at a prayer meeting run by Daniel Draper when he was 18 years old[13] so this would place Barker’s conversion in 1838 when he was around 12 years old.

(more…)Lady Lucy Forrest Darley (1839-1913), social position, charity and a glass of champagne

Lady Lucy Forrest Darley nee Brown(e) (1839-1913)[1] was born in Melbourne, the sixth daughter of Sylvester John Brown(e) (1791-1864) and Eliza Angell Alexander (1803-1889). On 13 December 1860, she was married in London to Frederick Matthew Darley, the eldest son of Henry Darley of Wingfield, Wicklow, Ireland.[2]

On 18 January 1862, she and her husband and a servant left Plymouth on the Swiftsure and arrived in Hobson’s Bay (Melbourne) on 19 April 1862. Six weeks later, on 1 June 1862, Frederick was admitted to the New South Wales bar on the nomination of John Plunkett QC.[3]

Lucy was to have six daughters and two sons. Henry Sylvester (1864-1917), Olivia Lucy Annette (1865-1951), Corientia Louise Alice (1865-1951), Lillian Constance (1867-1889), unnamed female (1868-1868), Cecil Bertram (1871-1956), Lucy Katherine (1872-1930) and Frederica Sylvia Kilgour (1876-1958). She sadly experienced the loss of one daughter at birth in 1868 and another daughter, Lillian, died from typhoid in 1889 when she was 22 years old.[4]

Lady Darley was active in charitable and philanthropic work and was a founder of the Fresh Air League, and one of the first members and the first president of the District Nursing Association. She also helped to form the Ministering Children’s League in Sydney, was keenly interested in the School of Industry, the Mothers Union, the Queen’s Fund as well President of the Working and Factory Girls Club and of the ladies committee of the Boys Brigade.[5]

She had gone to live with her husband in London in 1909 and died there in 1913. Her obituary in the Sydney Morning Herald noted that, during the time Sir Frederick Darley was Lieutenant Governor of New South Wales (NSW), Lady Darley gave her hearty sympathy and support to many charitable and philanthropic objects.[6] One might gain the impression from this statement that her charitable and philanthropic efforts were coincident with her husband occupying the role of Lieutenant Governor of NSW. In other words, it could be suggested that her involvement and philanthropic interest arose largely from her social obligations as the wife of the Lieutenant Governor. Was this a fair summary of Lady Darley’s charitable efforts?

(more…)William Ansdell Leech (1842-1895) and the Fresh Air League

On 25 September 1890,[1] in his parish of Bong Bong in the Southern Highlands of NSW, the Rev William Ansdell Leech, an Anglican clergyman, formed a Ministering Children’s League (MCL) group from which the NSW Fresh Air League (FAL) would arise. Initially, the activity that gave rise to the FAL was Leech’s particular way of fulfilling the ideals of the MCL. It soon became apparent that providing holiday accommodation for poor children and families in a healthy mountainous environment was a ministry deserving of its own name.

William Ansdell Leech (1842-1895) was the eldest son of Rev John Leech, MA, of Cloonconra County Mayo, Ireland, and Mary nee Darley, daughter of William Darley of St John’s County Dublin.[2] Leech matriculated to Cambridge University in Lent of 1865 and was a Scholar at the University from 1866. He was admitted to Lincoln’s Inn on 6 November 1866, gained a BA in 1868, and was called to the Bar on 10 June 1870 as a Barrister-at-Law. Leech went on to be ordained deacon by the Bishop of Wellington, New Zealand (and appointed a curate of Palmerston North) in 1883, before being priested by the Bishop of Bathurst in St Andrew’s Cathedral, Sydney, in December of that same year.[3]

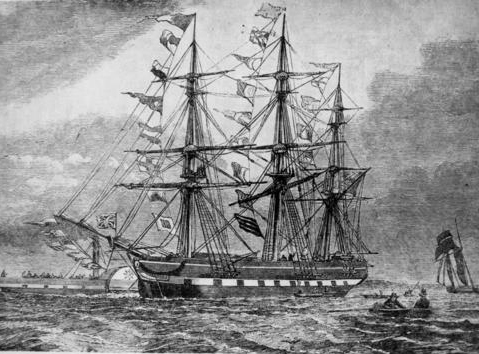

Travelling to New Zealand on the Dallam Tower

Leech’s first attempt to sail to New Zealand was not without incident for he travelled aboard the Dallam Tower which had left London on 11 May 1873, bound for Dunedin, New Zealand.[4] On 14 July, the ship met a ‘fearful hurricane’ and was dis-masted in latitude 46 degrees south and 70 degrees east. The vessel was at the mercy of the storm for some 14 hours after which the hurricane abated. Without a mast the ship was helpless, but after 11 days the Cape Clear, a cargo ship, came to their assistance and took off some of the Dallam Tower’s passengers who were in ‘a most forlorn and destitute condition. Their money, letters of credit and introduction, clothing and other necessaries gone.’[5] As one passenger remarked, they were fortunate not to have lost their lives:

But it was a mysterious Providence that sent the Cape Clear to our help. Had it not been for the distressing loss of two of their number we should never have seen her. One of the apprentices on the previous day had fallen from the rigging, and another in a noble but hopeless attempt to save him, went overboard after him. The ship delayed her course for several hours, while a boat was sent in a vain search for these poor fellows. Thus it was that she came up with us at the dawn of morning, otherwise they would have passed us in the night without seeing us.[6]

(more…)The Ministering Children’s League

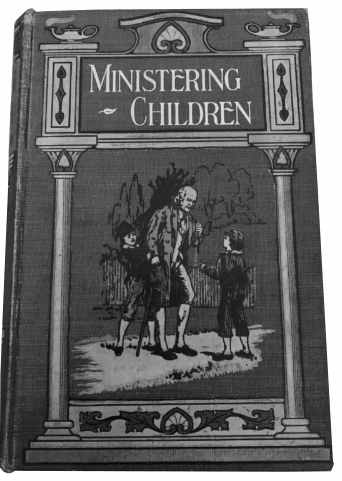

The Ministering Children’s League (MCL) was a British organisation founded in February 1885 by the Countess of Meath in her house at 83 Lancaster Gate, London.[1] In developing the MCL she was assisted by the Rev C J Ridgeway in whose parish of Christ Church Lancaster Gate the first group began.[2] The Countess was Mary Jane Brabazon (née Maitland) (1847-1918) and in January 1868 she married Reginald Brabazon who became the 12th Earl of Meath in May 1887.[3] Her inspiration in founding the MCL came from a book she had read as a child. Written by Maria Louise Charlesworth, it was titled Ministering Children and encouraged children to a lifetime of service to others.[4]

Maria Louisa Charlesworth (1819-1880) was the daughter of Elizabeth Charlesworth (née Beddome) (1783-1869) and the Reverend John Charlesworth (1782-1864), an evangelical clergyman who was Rector of Flowton, Suffolk, when Maria was born. He later became Rector of St Mildred’s, Bread Street, a London parish where Maria lived with him in the Rectory at St Nicholas Olave. A visitor to the poor in her father’s parishes from a young age, Maria drew on these experiences for her most popular book, the fictionalised Ministering Children (1854). Ministering Children sold over 300,000 copies during her lifetime and was designed to teach children, by example, to be kind to the poor. It was especially popular as a ‘Reward Book’ for Sunday School prizes.[5]

Charlesworth wrote in the book’s preface:

… it is necessary that the talent of money be not suffered to assume any undue supremacy in the service of benevolence. Let children be trained, and taught, and led aright, and they will not be slow to learn that they possess a personal influence everywhere; that the first principles of Divine Truth acquired by them, are a means of communicating to others present comfort and eternal happiness; and that the heart of Love is the only spring that can effectually govern and direct the hand of Charity.[6]

The MCL was not the only philanthropic activity of the Countess for she was a significant philanthropist. The Countess was responsible for the formation of the Brabazon Employment Society, established to provide occupation for those in Workhouse or Infirmary wards; the Meath Home of Comfort for Epileptic Women; Brabazon Home of Comfort for members of the Girl’s Friendly Society; the Brabazon House for Aged Ladies (Dublin); Brabazon and Hopkinson House which provided cheap accommodation for women in London; the Workhouse Attendants Society and the Workhouse and Hospitals Concert Society.[7] She also took an active role in the formation of the Girl’s Friendly Society (GFS) in England and Scotland.

(more…)Wilfrid Law Docker (1846-1919) Accountant and a thorough Anglican

Upon the death of Wilfrid Law Docker (often misspelled as Wilfred) it was said that death had removed one of those men who are the salt of the community and furthermore that:

There are many whose loss would attract greater notice, but there are few who will be so long and so much missed in a number of public affairs touching the religious and philanthropic, and educational interests of this city.[1]

Who, then, was Wilfrid Law Docker? What had he done in his life to be accorded the designation of ‘salt of the community’? And why would he be ‘much missed in … the religious and philanthropic and educational interests’ of Sydney?

Docker was born on 2 May 1846 to English-born Joseph Docker (1802-1884) and Scottish-born Matilda Brougham, Joseph’s second wife. The birth took place at Scone, NSW, on the family property Thornthwaite, and he was given ‘Law’ for his second name, the family name of his great-grandmother, Agnes (1737-1819). Joseph was a surgeon who arrived in Sydney in 1834 and took up 10,000 acres which he named Thornthwaite after the area from which he came in England; he became a grazier and politician. On the death of his first wife Agnes nee Docker (?-1835), Joseph returned to Britain and in 1839 married Matilda Brougham, the daughter of Major James Brougham of the East India Company, and his wife Isabella nee Hay. The service was conducted by Rev John Sinclair one of the ministers of St Paul’s Episcopal Chapel, York Place, Edinburgh.[2]

Wilfrid, along with his brother Edward, received his schooling at the ‘Collegiate School’ at Cook’s River (CSCR), Sydney, which was run by the Rev William Henry Savigny, an Anglican, educated at the Bluecoat School, London, and was an Oxford graduate. Prior to coming to NSW in 1853, Savigny had taught at Bishop Corrie’s Grammar School at Madras and at the Sheffield Collegiate School.[3] He earned

… a reputation for severe discipline, even in those ‘hard’ days, and when administering corporal punishment to the batch of boys — a most unusual occurrence — it was his custom to punctuate his strokes with quotations from the classics in Latin.[4]

The school was not cheap at 60 guineas per annum, paid in advance, for each quarter year. The course of instruction embraced the ‘classics, mathematics, the French and German languages, ancient and modern history, geography, and elementary natural philosophy’.[5] It was also said of the school that ‘Banking establishments of the town, the offices of solicitors, and the counting houses of merchants will furthermore establish the truth that … [the] School has fulfilled its functions in giving to boys of the colony a sound, liberal, and commercial education’.[6]

As the CSCR was a boarding school that did not accept boys until they were 10 years old, Wilfrid would not have gone there until May 1856 at the earliest. It is probable that Wilfrid was taught by Savigny for the whole of his time at CSCR for Savigny remained at the school for six years until 1862 when he was appointed Warden of St Pauls.[7] Around this time, Wilfred would have left school to begin his commercial career.

(more…)William Townley Pinhey (1820-1895) and the Benevolent Society of the Blues

In 1796, William Townley Pinhey (1781-1856) was apprenticed for seven years for the sum of £8 to his uncle and London grocer John Wilkes Hill.[1] Pinhey was the son of William Pinhey (1745-1789) a linen draper and his wife Mary Townley (1758-1838). That the apprenticeship fee was paid for by the treasurer of Christ’s Hospital, London, meant that William Townley had been educated at Christ’s Hospital which, despite the name, was actually a school and not a medical facility. At the time of its foundation the term ‘hospital’ meant ‘a place of refuge’. By the allocation of bursaries, Christ’s Hospital enabled boys from poor families to receive an education that would equip them for commercial or Naval service; girls also attended.

On 1 October 1805, after completion of his apprenticeship, Pinhey enlisted in the Royal Marines as a Second Lieutenant in the Woolwich Division. He joined H.M.S. Lion (64-guns) on 8 January 1806 and served his entire active service career aboard this ship. He was promoted to Lieutenant on 25 September 1809 and was First Lieutenant of Marines aboard the Lion at the capture of Java on 25 August 1811.[2] Pinhey was placed on half pay on 1 April 1817[3] and remained so at least until 1840.[4] He was awarded the Naval general service medal with Java clasp.[5]

On 20 May 1819, he married Ann Hobbs (1787-1821), and on 27 March 1820 at Shoreham, Sussex, Ann gave birth to a son who was named ‘William Townley Pinhey’ after his father (hereafter called Willliam and his father called William Snr).[6] Ann died one year later and William Snr married Mary Ann Kenny; between 1823 and 1829 she gave birth to four children. After his discharge from the Navy William Snr practiced as a surgeon so it appears that this was his role in the Navy.[7]

William Townley Pinhey

Just as William Snr attended Christ’s Hospital, so did William and he did so until he was fourteen.[8] It was intended that he, like his father, should join the Navy and in order to decide if this was the best career choice, William took a sea voyage upon the “Henry Porcher”, a convict transport bound for Sydney.[9] The captain, John Hart, was a relation of the Pinhey family. William disliked the sea voyage so much that he refused to return to England and elected to stay in the colony of New South Wales.[10]

William and Employment

Arriving in Sydney in January 1835 and having a good educational background, William was able to secure employment. He vacillated between the trade of a druggist (pharmacist)/grocer[11] and that of a lawyer. This duality of interest would later equip him for a significant medical/legal role that he played in the colony of New South Wales. Initially, he was employed by Ambrose Foss who had established himself as a druggist and grocer. In the nineteenth century, the grocery trade and the apothecary’s provision of medicine were closely linked. Fifteen months later, he was employed by George Allen, a solicitor. Shortly after this, Pinhey returned to pharmacy duties until 1841 when he once more worked for Allen and remained in his employment for four more years.[12]

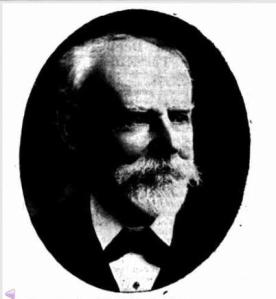

(more…)Archibald Gilchrist (1843-1896), servant of Christ

Archibald Gilchrist was born at Rutherglen, Scotland, on 22 March 1843[1] to Alexander Gilchrist (1813-1891) a cotton spinner,[2] and Catherine nee Henderson (1816-1881). Archibald was the fourth child of seven children, five of whom survived to adulthood: Alexander (1837-1916); Agnes (1847-1923); Ann (1849-1936); and Catherine (1853-1877).[3] Along with his siblings, Archibald came to the colony of NSW at the age of 10, arriving on the Empire in July 1853 with his parents.[4] He was thus ‘a Scotsman and not a whit behind the most enthusiastic in his attachment to “Caledonia stern and wild” but he came to regard Sydney’[5] and Australia as his home.

Gilchrist’s primary school education began in Glasgow, was recommenced in Sydney, but was interrupted for a few years as he took employment and was apprenticed to a trade. In what was to become a reoccurring pattern, his health broke down and he relinquished the position and went and spent some time with his brother Alexander and family on the goldfields near Braidwood.[6] On his return to Sydney, unemployed and again unwell, Gilchrist used his time in private study of English, Greek and Latin.[7] His father was encouraged[8] to send him to the Sydney Grammar School, which he entered when he was 17 years old. After 15 months at the school,[9] he took up private teaching and set up a school in his father’s parlour at 276 Crown Street.[10]

The Rev Dr Robert Steel, his minister, first suggested to Gilchrist the possibility of a teaching appointment at St Mary’s School. He also suggested that should Gilchrist secure such a position, he might also assist the Presbyterians on the Sabbath through preaching.[11] In the end, he did not undertake an appointment to the school but, in February 1863[12] and with the active encouragement of his minister and that of the Rev James Cameron, Gilchrist was appointed a catechist home missionary at Penrith, South Creek and St Mary’s in connection with the Synod of Eastern Australia.[13] He began his remarkable career as a preacher with his first sermon at St Marys on 22 February 1863 at 19 years of age.[14] His position at St Marys was an experiment in the use of lay preachers. It was noted that

in sending Mr. Gilchrist to Penrith, the Presbytery had tried an experiment as to the value of lay agency in the outlying districts, and much anxiety had been manifested in various quarters as to the probable result of such a trial.[15]

Both Robert Steel and James Cameron who had been instrumental in this matter believed that, due to the response of the people to the ministry of Gilchrist, the experiment was a success. It also affirmed Cameron’s view that ‘a man with a love for souls may be a very good preacher without much learning.’[16]

Gilchrist himself said about the appointment, giving an indication of the eloquent zeal that was to characterise his life, that his position had been

(more…)Andrew Torning (1814-1900) a not very useful addition?

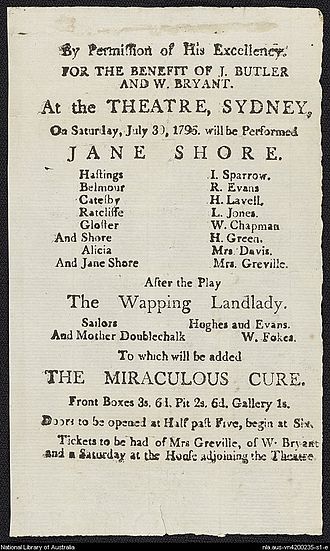

‘He is not calculated to be very useful here’ was a theatre critic’s verdict on Andrew Torning one month after Torning’s arrival in Sydney. Nearly 60 years later, a review of his life would recall him as a more than useful addition, and this usefulness extended to numerous areas in the development and growth of the colony of New South Wales. Andrew Torning was born in London, England, 26 September 1814, the son of Andrew Torning (1784-1815), Master Mariner, and Ann Dayton. It has been suggested that Andrew’s father was Danish, as the name ‘Torning’ is present in Scandinavia, however, there is no evidence to support this suggestion.[1] His father was the Master of the vessel Hamilton and he drowned on 9 September 1815 when his ship was lost in a gale while sailing between Jamaica and London.[2]

Andrew, who was a painter of both houses and theatrical backdrops, married Eliza Crew at St. Leonard’s church, Shoreditch, England, on 9 July 1832. They had two children, Thomas Andrew (1834-1868) and Eliza (1836-1862), and by 1841 were living in Provost Street, Hoxton, New Town.

On 18 May 1842, Andrew and Eliza were onboard the barque Trial as it left Plymouth bound for Sydney via Rio de Janeiro and they arrived in Sydney on 21 October 1842. This concluded a long and slow journey in which the trip to Rio de Janeiro had taken 15 or so weeks when it normally took seven.[3] What was the inducement for Andrew and Eliza, with their two young children then aged eight and six, to leave England and come to Australia? The answer is ‘the theatre’.

Colonial Theatrics

Joseph Wyatt was the owner of the Royal Victoria Theatre in Sydney and he had decided he needed some fresh performers for his theatre. In order to obtain them, he boarded the Royal George and left Sydney on 21 March 1841 bound for London.[4]The Sydney public was informed that

Mr Wyatt, is about proceeding to England, where that gentleman proposes to engage an efficient number for all the several branches of the department. For the professional part of Mr Wyatt’s embassy, we confidently rely on his judgment and liberality; and in his private relations …[5]

During 1841 and 1842, Andrew and Eliza were both performers at the Royal Albert Saloon, Shepherdess Walk, City-road, London. This was a minor theatre and was part of Henry Bradley’s Royal Standard Tavern and Pleasure Gardens. It featured concerts, vaudevilles, melodramas, animal acts, fireworks, ballooning, and weekly dances, and the price of admission was usually not more than sixpence.[6]

The couple had adopted the ‘stage name’ of Mr and Mrs Andrews, she as a dancer[7] and he, in the company of others, doing ‘Herculean Feats’.[8] Learning that they were leaving for Sydney, the Royal Albert Saloon Company gave a benefit in their honour.[9] The Company’s Saloon was a conveniently situated venue for the couple as they lived in Provost Street which was a short walk from the theatre. Andrew was a painter by profession and, as he later showed significant skill in painting theatre backdrops (or act drops),[10] this probably was his main source of income and it is doubtful that their theatrical efforts gave them much financial security. The opportunity to come to Sydney meant an increase in income as the average stipend for those who performed at the Albert Saloon was between 15 and 25 shillings whereas in Sydney they would earn from four to six pounds.[11] Sydney was also possibly an enhanced opportunity to be more engaged in the theatre.

(more…)The Consumptive Home

In the colony of NSW during the late 1870s, tuberculosis was a considerable health problem and was perhaps the single greatest cause of death in that period.[1] In September 1877, the Sydney timber merchant and philanthropist John and his wife Ann Goodlet[2] together began their work of caring for consumptives. They leased a property in Picton which was called ‘Florence Villa’,[3] and in September 1886 expanded the charity with a new purpose-built facility in Thirlmere. These facilities were not hospitals but, as their name implied, a home to which sufferers could go for care and shelter. They were more sanitaria than hospital except that, unlike their overseas equivalent, they were not for the wealthy who could pay often considerable sums, but for the poor who could not afford such amenities.[4] This institution was the only one in the colony of NSW dedicated to those who suffered from this disease until St Joseph’s hospital was opened in July 1886 in Parramatta.[5] These institutions remained the only ones dedicated to the care of consumptives until April 1897 when Lady Hampden decided, as a way to mark Queen Victoria’s Jubilee, to raise funds in order to build a Queen Victoria Home for Consumptives.[6]

John Mills (1829-1880) wholesale grocer and governance philanthropist

John Mills was born in 1829 in Tidworth, Wiltshire, to James Mills, a farmer and his wife Charlotte nee Mackrell.[1] John was a cigar manufacturer[2] but was listed as a clerk when he came to the colony of Victoria. He arrived on the Nepaul at Port Philip Bay on 20 October 1852, while on 24 November 1852, Emily Stidolph (20 June 1826-27 June 1887) arrived on the Chalmers. John and Emily were married on 14 January 1853 at the Lonsdale Street Congregational Church[3] and were to have eight children: William Mackrell (1854-1931), Caroline Eliza (1856-1914), Stephen (1857-1948),[4] Emily (1862-1940),[5] Lucie Ellen (1863-1948),[6] Arthur John (1865-1916),[7] Evelyn Clara (1867-1954)[8] and Sylvia Hannah (1869-1927).[9]The Mills soon moved to Sydney and lived firstly at 11 Botany Street and then at 78 Albion Street, Surry Hills, from at least 1862 until 1872 when they moved out of the city to the semi-rural setting of ‘Elston Villa’, Alt Street, Ashfield.[10] In 1879, the impressive ‘Casiphia’ was constructed in Julia Street, Ashfield, and was occupied by the family.[11]

John Mills died in 1880 at the age of 51,[12] leaving Emily with eight sons and daughters aged between 11 and 26 years. He was buried in the cemetery adjacent to the Dobroyde Presbyterian Church.[13] Emily moved from their home ‘Casiphia’[14] in Ashfield to ‘Aurelia’ in Liverpool Road, Croydon, where she died in 1887 aged 61.[15]

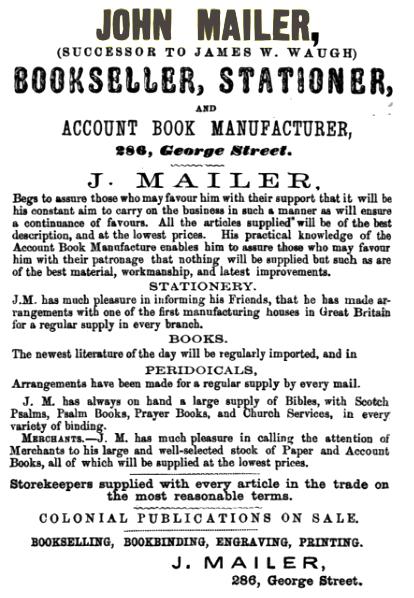

The Wholesale Grocer

When and how John came to be employed in Sydney is unknown. He may have placed an advertisement like the one below for it fits him well; he was at that time 24 years old, married, and he did end up working in the grocery business.[16] It is known that he was in Sydney by June 1853[17] but not if he was employed in the grocery trade by that time.

The first ‘grocery’ reference to John Mills is in December 1854 in Sydney where he was, as a grocer’s assistant, in the employ of William Terry, Wholesale Grocer. John, along with 34 other grocer’s assistants, had petitioned their employers to rationalize the business hours that they were expected to keep.

Their argument was that

… we need not enumerate the many advantages that would be derived by us, in allowing more time for moral improvement and healthful recreation, and after carefully studying our employers,[sic] interest and making that our great desideratum, we must respectfully submit for their approval the following proposal: …

Their proposal was to restrict business hours so ‘That business be closed every night at seven o’clock, except Saturday, on which night close at ten o’clock. To commence January 1st, 1855’.[18]

John worked for William Terrey as his shop man and he was conscientious. One incident in his life as a shopkeeper made the newspaper in 1855. On entering the shop, Mills had noticed a boy leaning over the counter with his hand in the till. As soon as he saw Mills he took off as did his companion cockatoo who was meant to give a warning. Mills gave chase and finally caught them both. The young thief admitted to taking 10 shillings and offered to return it on condition he be let go. This was not agreed to but the 10 shillings was handed over anyway and off to the Police he was taken. On searching him, a florin from the shop was found. As there was not enough evidence to convict the cockatoo he was sent home. The young thief, however, since it was his fifth offence in less than a year, was given three months jail; he was ten years old.[19]

(more…)George Collison Tuting (1814-1892)

an aspiring but ordinary nineteenth-century colonist

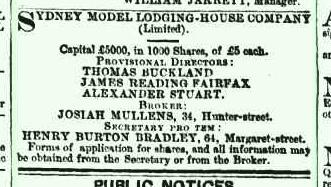

George Collison Tuting was not an outstanding figure in nineteenth-century NSW. Coming to the colony he hoped to better himself and his family in the drapery business which was a trade he knew well. On arrival he was socially well connected through marriage to the Farmer family (Farmers & Co). He was welcomed into the Pitt Street Congregational Church’s merchant circle (including G A Lloyd, Alfred Fairfax, David Jones) and while he had great aspirations he failed to convert them into business success. His early philanthropic endeavours were quickly extinguished by his failure in business; bankruptcy does not enhance one’s ability to be philanthropic. In the latter phase of his life, having obtained a certain level of financial stability, he gave of his time to help organize various philanthropic activities mostly promoting spiritual engagement.

Tuting was born in Beverley, Yorkshire, England, in January 1814 and was the son of Jeremiah Tuting, variously a cordwainer (shoemaker) and sexton of St Marys’ Church, Beverley, and Sarah Collison.[1] In 1841, George married Eliza Bolton (1817-1847) and they had 5 children: William Collison (1841-1918), George Bolton (1843-1843), Eliza Bolton Kent (1844-1883), Emily Sarah Parsons (1846-1924) and Henry Gutteridge (1847-1847). Eliza died in March 1847[2] and on 9 February 1848, George married Mary Petford nee Farmer (1804-1868), the widow of Jason Petford, a draper in Brierley Hill. Mary and Jason, had married in 1827[3] and had two daughters: Mary (1834-1858) and Amelia (1843–1928).

The Tuting family left England 8 November 1849, on the Prince of Wales and arrived in Sydney on 21 February 1850. The family group consisted of George and his wife Mary and George’s son William, his daughters Eliza and Emily, his nephew Thomas Shires Tuting together with Mary’s two daughters, Mary and Amelia.[4]

In England

George was a draper and his first shop was in the Market Place, Beverley, and while it is unknown when he began business, the first evidence of its existing is from 10 April 1840 when he sought to commend his goods to the public through the distribution of printed hand bills.[5] He was a religious man who, when advertising for staff, made a point of indicating that ‘a man of piety will be preferred’[6] and when seeking an apprentice gave the assurance that his ‘Moral and Religious training will be strictly attended to, as well as receiving a thorough knowledge of the Business.’[7] He was, as a churchman, a Congregationalist attending the Independent Chapel, Beverley, and later at Brierley Hill.[8]

It would appear that George was interested in missions, financially supporting a young Indian man from 1846-1849 so that he could undergo training for ministry at Bangalore, India.[9] He also gave money to a Medical Institution[10] and towards the building of a Mission College in Hong Kong.[11] The Missionary Magazine and Chronicle, a publication mostly concentrating on the work of the London Missionary Society, was itself largely supported by Independent Churches. That his financial support of missions was recorded in this publication is consistent with his churchmanship being congregational.

(more…)Bush Missionary Society – the early years up to World War 1

In 1861, the Queanbeyan-based newspaper ‘The Golden Age’ reported a case which it regarded as one of ‘rank heathenism’ and ‘an instance of the most lamentable ignorance it is possible to conceive of, as existing in a professedly Christian country’.[1] The ‘rank heathenism’ and ‘lamentable ignorance’ concerned a 12-year-old boy named Hobson and his lack of even a basic civilising experience of school and church or an understanding of the Christian faith. He was to testify in the Small Debts Court, but before he was sworn in to give evidence the Police Magistrate asked him a few questions:

PM How old are you?

Boy Don’t know.

PM Have you been to school?

Boy No.

PM Ever been to church?

Boy No.

PM Do you say any prayers?

Boy No.

PM Ever heard of God?

Boy No.

PM Ever heard of heaven or hell?

Boy No. [and after some hesitation] Yes, I think I have.

PM What people go to heaven when they die?

Boy Bad people.

The newspaper then commented on the situation and suggested a remedy:

Who the parents of the boy are, we know not; but such a specimen of rank heathenism we never heard of in a so-called Christian country. We draw the attention of the committee of the Bush Missionary Society to this case.[2]

The isolation of the ‘bush’ in colonial Australia meant that there were many, like young Hobson, who were never exposed to the Christian message, worship and prayer and were thereby ignorant of its precepts; the problem was recognised, but it was difficult to address. An attempt, however, was being made to address this lack of Christian ministry through the distribution of bibles and religious literature by colporteurs, and it was to this ministry of the Bush Missionary Society (BMS) that the Queanbeyan newspaper ‘The Golden Age’ looked in order to address the problem.

The BMS was, however, not the first in the colony of NSW to seek to deal with the issue of the spiritual neglect of the bush through the use of colporteurs. This honour belongs to James Robinson, colporteur with the Bible Society, who was the first to provide a ministry of bible distribution to the sparsely populated rural districts. In 1852, Robinson began his work in ‘the bush’ and in his helpful article Gladwin says that:

Robinson’s journeys were the first of many undertaken by dozens of colporteurs—across the Australian continent—on behalf of Australian Bible Society agencies during the second half of the nineteenth century. They provided important pastoral and evangelistic ministry to sparsely populated rural districts in the decades before the creation of dedicated ministries such as the Anglican Bush Brotherhoods (1897–1920) and the evangelical Anglican Bush Church Aid Society (BCA, founded 1919).[3]

Well before the commencement of the Anglican bush ministries that Gladwin mentions, and only a few years after the commencement of the work of the Bible Society, the ministry of the non-denominational Juvenile Missionary Society (JMS), later known as the New South Wales Bush Missionary Society (BMS), was inaugurated.[4]

(more…)More light on the founders of The House of the Good Shepherd

‘… by a few zealous ladies’

The precise origin of ‘The House of the Good Shepherd’ [HGS] in Sydney as a Catholic refuge for women and who was involved in its commencement, is a little uncertain. The various accounts that are given in an attempt to recall its commencement agree in the main but differ in the detail. New information, however, has come to light which would suggest, as this paper will argue, that some adjustment to the accepted narrative of events and persons involved needs to take place.

Simply put, the Catholic tradition[1] on the origin of HGS that has come down to us is that:

On a Sydney street in 1848, Father Farrelly of St Benedict’s Mission met a woman who was tired of life as a prostitute and begged him to find her a place where she could rest and rescue her soul. Farrelly placed her in the care of Mrs Blake, a Catholic laywoman, and when six more women asked for assistance, Polding instructed Farrelly to rent a house in Campbell Street. Mrs Blake looked after these women in the rented house[2] and, while the establishment was under her control, the Sisters of Charity visited to instruct the residents in the elementary tenets of their religion.[3] Archbishop Polding was anxious to make some permanent arrangement for the increasing numbers who were seeking shelter so he together with the Sisters of Charity established the Magdalen House in 1848,[4] which was soon after renamed ‘The House of the Good Shepherd’.[5]

(more…)Thomas Bately Rolin (1827-1899) Governance Philanthropist

Thomas Bately Rolin was born in King’s Lynn, Norfolk, England, on 4 September 1827 to Daniel Rolin (a shoemaker) and Ann Bately.[1] He was the youngest son of a family of at least six children. Leaving England in January 1854, he arrived in Melbourne on board the Croesus on 9 April 1854.[2] He remained in Victoria for eight months and then, in December 1854, he came to Sydney aboard the Governor General.[3]

In Sydney in May 1857, he married Louisa Jones (1835-1872)[4] the London-born third daughter of Thomas Jones (1796-1879)[5] and Elizabeth nee Smith (1798-1861).[6] Thomas, who was the brother of David Jones of David Jones & Co,[7] was a ‘broker’ or ‘commission agent’ and appears to have arrived in the colony of NSW in 1836.[8] Very little is known about Louisa’s parents or herself except that she had six children with Thomas Rolin: Minnie (1858-1899),[9] Tom (1863-1927),[10] Mildred (1865-1888),[11] unnamed male child (1867),[12] Gertrude (1868-1918)[13] and Frederick Lynne (1870-1950).[14] Thomas and Louisa settled in “Forest Lodge” on the corner of Pitt and Redfern Streets, Redfern, living there at least until 1871[15] when they moved to Burwood. It was here that Louisa died[16] in 1872 leaving Thomas, who never remarried, with children aged 14, 9, 7, 4, and 2. In 1880, Thomas took up residence in Redmyre Road, Strathfield, where he remained until his death on 26 June 1899.[17]

Thomas came to Australia in because of a business partnership he had with his older brother William Salmon Rolin (b 1821). William was a joiner by trade but had an entrepreneurial flair and became a property developer. As such, in 1848 he employed some 35 men on his building of houses and in renovating the Framingham Almshouses.[18] It would appear that he and Thomas formed a partnership as ‘Ship Builders and Shipwrights’ in King’s Lynn.[19] By October 1854, however, the partnership was bankrupt with debts said to be in excess of £20,000 ($1.6 M) with no assets available to offset this sum. William absconded to the United States of America where he took out citizenship,[20] whereas of Thomas, it was said:

About nine months since Mr. T. B. Rolin left England for the purpose of looking after the affairs of the partnership. It was no doubt necessary for him to do so, as the bankrupts were owners of vessels several of which were at Australia … Now the probability was, that Mr. T. B. Rolin knew nothing of the bankruptcy … it was probable that he did not know the firm was insolvent at the time he left England.[21]

In view of this, William Rolin was declared outlawed, but T B Rolin had his examination adjourned ‘sine die’ to allow him the opportunity to communicate with his assignees.[22] T B Rolin, however, never returned to England and the matter was never resumed. Whether Thomas’ absence in the colony was fortuitous or by design is unknown. That it was fortuitous is supported by it being publically stated that Thomas had not planned to remain in the colony of NSW being ‘temporarily in the colony’.[23] Probably, when he learned of the bankruptcy of Rolin and Rolin shipbuilders, it was a prudent if not an altogether ethical course of action. No doubt he said nothing, for someone who was a known bankrupt and in debt to creditors for such a large sum would find it difficult to build a future. This situation also explains why, later in life, when successful and prosperous, he did not return to England for a visit as so many other colonists had done. Whereas England now offered Thomas only difficulties, Australia was to prove to be an opportunity for advancement and for a second chance to build a successful, respectable and prosperous life. Given that his chosen profession of advancement was the law, being a bankrupt would not be an asset in assisting him to become a qualified solicitor.

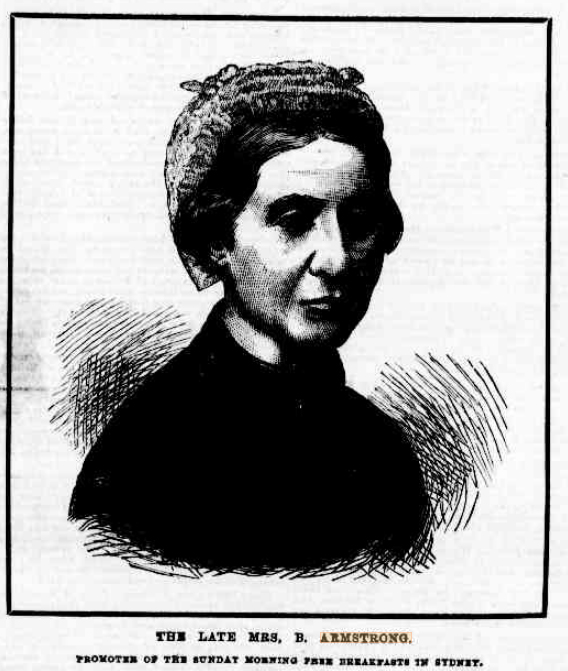

(more…)Andrew Bell Armstrong (1811-1872)

Founder of the Sunday Morning Breakfast for the Poor

Andrew Bell Armstrong was born in Ireland around 1811 and died in Sydney on 17 June 1872, at 61 years of age.[1] Andrew married Barbara Iredale on 20 July 1844 in Sydney[2] and they were to have three children: Mary (b 1846), Thomas (b 1849) and John (b 1851). Barbara was to prove to be a willing partner in Andrew’s philanthropic efforts. Barbara Iredale was 28 years old on her arrival in the colony in 1842. She came with her mother and father, and she had with her a daughter, Sarah, from a previous relationship who was born in 1841. Sarah would later marry WS Buzacott who would be Andrew’s business partner.

Military Background

Andrew came from a family with a military tradition, and he said he descended from ‘a long line of British soldiers’. All his uncles were in the army and his father was a volunteer[3] and so he uncritically followed the family tradition when he joined His Majesty’s (HM) 80th Regiment of Foot (also known as the Staffordshire Volunteers). Later in life he was to rethink his attitude to soldiering. HM 80th Regiment of Foot had a proud history with extensive overseas engagements but, prior to Armstrong joining the Regiment, it had been stationed from 1831 in various parts of England and Ireland. This is most likely when Andrew, being Irish, joined the Regiment.[4] A detachment of the Regiment sailed from England on 23 May 1836 for Sydney with the task of accompanying a group of convicts. The remainder of the Regiment with its colours, and presumably Armstrong who was a ‘colour serjeant’, did not leave until 6 March 1837 and arrived in Sydney on 11 July of that year. The Regiment’s duties meant that,

During the stay of the 80th in New South Wales, it has been divided into a great number of very small detachments, distributed over nearly the whole colony, chiefly guards over prisoners at stockades – a duty harassing to the soldier and prejudicial to discipline.[5]

The almost unknown founders of the Sydney Magdalen Asylums

In the second half of the nineteenth century, Sydney had two Magdalen Asylums to provide prostitutes with shelter and a chance for them to redirect their lives. Both were formed in 1848, and both were housed in Pitt Street, Sydney, next door to one another in the former Carters’ Barracks. One was the Catholic ‘House of the Good Shepherd’ (HGS) and the other, the effectively Protestant ‘Sydney Female Refuge’ (SFR).

In the formation of each of these Asylums were figures, a woman in the case of the HGS and a man in the case of the SFR, who were critically important but who received little recognition and whose identity is uncertain. This paper is an attempt to redress this obscurity and to suggest the identity of these important but neglected figures of the Sydney Magdalen Asylum history.

Mary Blake and the House of the Good Shepherd

Catholic tradition has it that

… on a Sydney street in 1848 Father Farrelly of St Benedict’s Mission, met a woman who was tired of a life as a prostitute and begged him to find her a place where she could rest and rescue  her soul. Farrelly placed her in the care of Mrs Blake, a Catholic laywoman, and, when six more women asked for assistance, Polding instructed him to rent a house in Campbell Street.[1]

her soul. Farrelly placed her in the care of Mrs Blake, a Catholic laywoman, and, when six more women asked for assistance, Polding instructed him to rent a house in Campbell Street.[1]

The precise identity of Mrs Blake is never revealed except to say that she was a Catholic and that she cared for the women in premises in Campbell Street which either she or Farrelly rented. Mrs Blake was probably Mary Blake (1802-1857), born in the City of Dublin and arriving in NSW sometime before 1837 or perhaps as early as 1835.[2] After the founding of the HGS, she became a collector for it from its first year of operation in 1848 to at least 1853.[3] When Mary died in 1857, her funeral procession moved ‘from her late residence, at the house of the Good Shepherd, Pitt-street.’[4]

Mary was said to be the wife of John Christopher Blake, also known as Christopher Blake (1796-1844), the publican of the Shamrock Inn in Campbell Street. John Blake, the name by which he was most commonly known, had previously been a constable and poundkeeper at Stonequarry (Picton),[5] but in 1840 he was appointed to the Water Police in Sydney.[6] In 1841, he resigned and in July became the Publican of the Shamrock Inn at the corner of Campbell and George Streets, Sydney.[7] Blake had arrived in NSW in 1818 as a convict transported in the Guilford (3), and in 1826 he married Jane Sterne;[8] they had one son Christopher John Blake (1828-1856), but Jane died in 1831. In 1833, Blake made an application with Mary McAnally/McNally, transported on the Forth 2, to marry and permission was given, but it appears the wedding never took place as it seems McAnally/McNally was already married.[9] Who, then, was Mary Blake if not Mary McAnally/McNally? There is no record of John Blake’s marriage to anyone else and so it would appear that his wife, Mary Blake, may have been a common-law wife and her maiden name or name on arrival in the colony is unknown.[10]

William Henry Simpson (1834-1922), Saddler, Mason, Local Government – a governance philanthropist

On the death of William Henry Simpson in 1922 it was said that ‘Sydney has lost a good, useful citizen’.[1] Who was this good citizen and how had he been useful? Of his wife Ann, it was said that she ‘was well known in charitable and church work in Waverley, and was highly esteemed by all who knew her’[2]. In what way had these good citizens contributed to the nation of which they were a part?

Background and Business Life

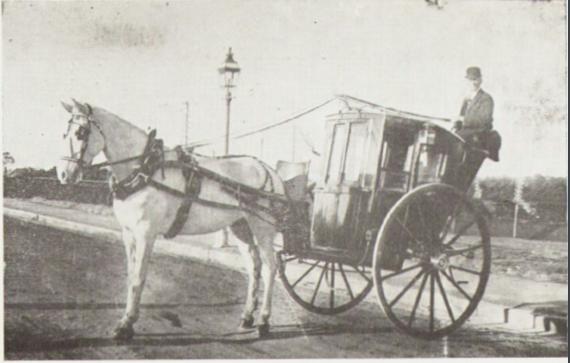

William Henry Simpson was born at Warrenpoint, County Down, Northern Ireland in 1834 to Ebenezer (1795-1855) and Sarah Simpson (1796-1878)[3] and arrived with his parents in Australia in 1838 aboard the ship Parland.[4] At Newry in Ireland, Ebenezer had been a master tanner and so when he arrived in Australia with his family, settling first at Windsor then at Richmond, he worked for Wright’s tannery in Parramatta.[5] In 1843, he commenced a tannery business at Camden, NSW.[6] While William’s brothers, Ebenezer (Jnr) and Alexander, were to become tanners and join the family business,[7] William was apprenticed as a saddle and harness maker to William S Mitchell of Camden[8] for the period from around 1848 until 1855.[9] Emerging from his indentures in 1855, it is said that William entered into a partnership in a saddle making business with Thomas Davis. Davis died in July 1855[10] and the partnership in the name of Simpson and Davis first saw the light in June 1856.[11]

It appears that William initially worked with Davis but on his death, which took place soon after William joined the saddlery, he entered a business partnership with Thomas’ widow. The saddlery was situated in various Pitt Street North addresses, but from January 1859[12] William had no partner. In 1861, he entered a partnership with James David Jones at 325 George Street[13] with the business name of Jones and Simpson. This partnership continued until 1863[14] when Simpson assumed sole ownership of the business which became W H Simpson, Saddler.[15] In 1887, his son William Walker Simpson joined him as a partner and the business was designated, W H Simpson and Son.[16] Simpson carried on in business until 1910 when he retired and the business was sold.[17] He had conducted a successful and prosperous business as he sold a commodity, equipment for horses which was central to personal and commercial transport, and which was in demand. At his retirement in 1910, however, he remarked:

Yes, I suppose the saddlery business generally it has made great strides, but in some respects it has fallen off. The coming of the motor car has, for instance, meant the making – taking into account the increase of population – of far fewer sets of carriage harness. Where nowadays you see a long row of motor cars lined up opposite the big shops in Pitt street, you used to see as many carriages. Everyone who was at all well off used to have his carriage and pair, and very smart most of them were. On the other hand the growth of the farming industry has made, a wonderful difference in the amount of harness made for farm-work. In fact, it is almost impossible to keep pace with the orders that come in.[18] (more…)

Public opinion and the provision of a Magdalen Asylum in Sydney

At a meeting of the St Patrick’s Society in Sydney in 1841, the Rev Joseph Platt, a Roman Catholic priest, proposed the formation of

a society among Catholic ladies for the establishment of a Magdalen asylum, or an institution which would afford a refuge to such unfortunate females as are in some measure driven to destruction by circumstances, and to those who, having erred, would gladly forsake their evil courses had they a home and a friend to whom they could fly for protection.[1]

Platt clearly thought of his proposed Magdalen Asylum as a Catholic concern.

At a public meeting in April 1842, the Hobart Magdalen Society was formed by the local community for the purpose of developing an Asylum. In July 1843, it reported some encouraging results, but it had not managed to obtain a property to open as an Asylum.[2] In the following month, a Catholic Magdalen Asylum in Hobart was contemplated by the Rev John Joseph Therry. He confidently publicised his expectation, possibly not to be outdone by the already existing Hobart Magdalen Society, that the Sisters of Mercy would soon arrive and a Catholic Magdalen Asylum for the reception of Female Penitents would be opened and placed under their direction.[3] The Sisters did not arrive, however, and the Asylum of which Therry spoke did not eventuate.

In Sydney in January 1843, the Sydney Catholic Australasian Chronicle reported that a ‘proposition is on foot for the establishment of a Magdalene asylum’,[4] and in March a letter appeared in the SMH pointing out the need for an asylum for prostitutes and asking the Mayor to initiate such an institution.[5] Nothing eventuated, but the matter of a Sydney Magdalen Asylum was again raised in a letter to the SMH in January 1846 and, in the following month, in the Catholic Morning Chronicle. These letters discussed the problem of prostitution and made a suggestion of publicly naming and shaming those landlords who allowed their properties to be used as brothels. They also called for the ‘philanthropic and humane’ to assist in the provision of a Magdalen institution.[6] The consciousness of the need, and perhaps a desire to set up a Magdalen Asylum, seems to have been impressed on some in the Catholic community for at his death in January 1846, George Segerson, a Catholic publican, left a legacy of £50 towards the ‘establishing of a Magdalene Asylum in the City of Sydney’.[7] Later, in April 1846, the Sentinel was direct when it said:

… we exhort and implore the virtuous and happy of the female sex, to look with a more favourable eye on the distresses of these unfortunate creatures who are now pining in degradation and misery; and to unite their influence, which is supreme, over their aristocratic lords, for the benevolent purpose of establishing an Asylum for such as choose to abandon the error of their ways, and to embrace a more reputable line of life. Let a committee of ladies, headed by Lady Gipps, Lady O’Connell, Lady Mitchell, Mrs Thompson, Mrs Riddell, Mrs Plunkett, Mrs Therry, Mrs Stephen, and as many more as they choose to select, be formed for the purpose of carrying out this desirable object – and a Magdalene Asylum for the reformation, protection, and salvation of hundreds of unhappy females raise its head, conspicuously in the City of Sydney …[8]

Alan Carroll (1827-1911), Doctor, Scientist, Philanthropist, Fabricator and Liar

The death of Dr Alan Carroll in 1911 was announced to the public in Sydney and beyond with the headline “A Great Man Gone, Doctor, Scientist, and Philanthropist”. Was he really any of these things? Under the headline he was described as ‘not only a wise physician but a philanthropist, who lived for the good that he could do’.[1] Regional papers said that he was a ‘great and good man, who had no thought for himself, but spent all for those who needed his help and advice’.[2] His ardent supporters considered him ‘the greatest and noblest man in Australia’ and ‘one of the greatest minds of the day’.[3] For his medical work he was spoken of in messianic terms as he made ‘the deaf to hear, the blind to see, the lame to walk, and the crooked straight’. [4] His life was indeed extraordinary, remarkable, colourful and varied as the headline announced, but his history is somewhat less great and his accomplishments less certain than the above would suggest. This article seeks to examine Alan Carroll’s life and some of the claims made by and about him concerning his qualifications, expertise and experience. It will become apparent that, whatever else he may have been, Carroll was an outright liar and a fabricator of his qualifications and experience.

Dr Samuel Matthias Curl alias Alan Carroll

Dr Samuel Matthias Curl alias Alan CarrollPersonal Details

A chronology of his early life, and some recounting of aspects of his background, is required to test the veracity of the various claims made in connection with that life. Critical to this assessment is to know when Alan Carroll was born. He was baptised with the name of Samuel Matthias Curl and he is commonly said to have been born in c1823.[5] Curl was actually born on December 31, 1827, and he was baptised on February 24, 1828.[6] He died in Sydney on April 17, 1911, aged 83 and 4 months.[7] He was the son of Matthias Curl, a wheelwright, and his wife Maria Howlett. Samuel grew up in London in a house in Regent Street[8] having one brother, William Matthias, who followed in his father’s trade.[9] In March 1851, Samuel married Mary White Pryce (December 3, 1820 – May 31, 1905).[10] In June 1851, he joined the Freemasons, St Johns Lodge, Hampstead (United Grand Lodge of England).[11] He maintained his membership until May 13, 1854, when Samuel and Maria embarked for New Zealand (NZ) aboard the Cordelia arriving in the colony at Wellington on September 29, 1854.[12] In 1855, Samuel’s uncle, a brother to his father, died and left him £100 sterling and his farm in Greater Walsingham, England, the income from which meant Samuel was financially secure and perhaps independent of the need to earn a living.[13]

In 1855 in NZ, Curl bought a property and took up farming and combined it with a medical practice and his literary work[14] firstly at Tawa, and then from 1862 at (more…)

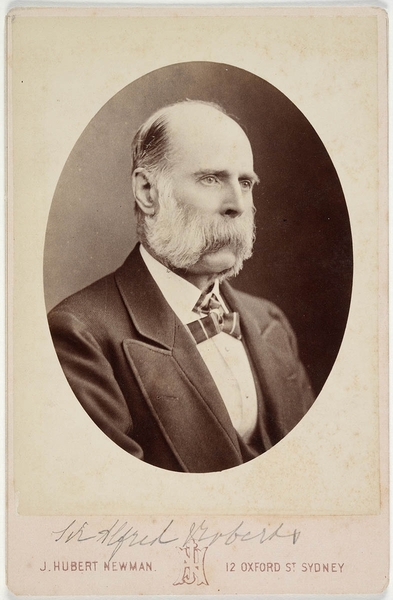

Wilhelmina Logan Stanger-Leathes (1826-1919); philanthropist in Bowral and beyond

Wilhelmina Logan Stanger-Leathes was the daughter of Thomas and Jane Ranken and was born in Ayr, Scotland, in 1826 and died in Sydney in 1919.[1] She was married in Scotland in 1850[2] to George Graham Stewart of Bombay,[3] but it seems that her husband died not long after their marriage. By 1859 she, known in the family as Willie, was living with her mother Mrs Thomas Ranken at Kyle, near Marulan, NSW, on the property of her uncle Arthur Ranken.[4] In 1868, she married Alfred Stanger-Leathes (1822-1895)[5] a company manager, and it was also his second marriage. His first wife Maria died in 1865 having borne Arthur seven children who were aged 17, 16, 14, 11, 9, 7 and 6 when he married Wilhelmina and she immediately became ‘mother’. The ceremony for Alfred and Wilhelmina was conducted by the Presbyterian Rev William Ross at Marulan, NSW, on Wilhelmina’s uncle’s property Lockyersleigh. Wilhelmina had no children from either of her marriages.[6]

Alfred had arrived in NSW in 1842 and was involved in various ways in the mining industry, principally in a copper mining and smelting operating on the Island of Kawan,[7] New Zealand, around 1846 until 1851.[8] The ore was mined and smelted on the island and shipped to London via Sydney, and he also exported a minor amount of gold to England.[9] He and his first wife Maria and child returned to England in 1852, returning to Sydney in 1854.[10]

On the amalgamation of the Australasian, Colonial and General Fire and Life Insurance and Annuity Company with the Liverpool, London and Global Insurance Company in August 1854, and the resignation of the resident secretary Robert Styles, Alfred was appointed its secretary. He held this position until 1880[11] when he resigned and was appointed to the board of directors in which position he continued until his death in 1895.[12] At one time, he was also a director of the Colonial Sugar-refining Company (1870-1880, 1882-1883).[13] In 1892, Alfred built The Rift at Bowral on a property of 20 acres which was described as having been erected by Alfred ‘regardless of cost, and with mature judgement and excellent taste”.[14] Alfred had become a wealthy man and on his death in 1895 his estate was valued at £52,000 ($7.88M current value) with shares in excess of £23,000 ($3.50M current value).[15]

Wilhelmina’s marriage to Alfred granted her a social standing that she would use to good effect in promoting her philanthropic interests. She appears to have had the contacts and social standing required to persuade the wife of various Governors to be present or to chair meetings or open a garden party for causes in which she was involved. The name ‘Stanger-Leathes’ sounded somewhat pretentious and perhaps went down well in ‘fashionable’ circles. It was derived from Alfred’s family background for when his ancestor Thomas Leathes died in England in 1806 his estate, consisting mainly in Lake Thirlmere in Cumberland, was entailed away to his cousin Thomas Stanger who changed his name to include that of his beneficiary and so the family became known as Stanger Leathes. It would appear, however, from two anecdotes in the Bulletin, that Alfred, at least, much preferred to simply use Leathes. Firstly, according to the Bulletin:

The late Edward Deas-Thomson, before his knighthood, was a director at Sydney of the Liverpool and London and Global Insurance Co., [sic] at which Alfred Stanger-Leathes was secretary. At a board meeting one day, Mr Thomson said “Mr Leathes ___ “ “I beg your pardon. Mr Thomson, my name is Stanger-Leathes” “And mine,” quoth the ex-Imperialist, “is Deas-Thomson.’[16]

Henry Phillips (1829-1884) and Margaret Thomson (neé Stobo) (1852-1892) and the Deaf, Dumb and Blind Institution

Henry Phillips[1] was the son of William Phillips and Sophia (nee Yates) who were both transported to Australia for fourteen years for “Having & Forged Banknotes.”[2] Both arrived in the colony of NSW in 1820, but William came on the Coromandel whereas Sophia came on the Janus with their seven children aged between 2 and 16 years (including some from William’s previous marriage). Sophia was then assigned to William as a convict, and they recommenced family life in the colony. He was granted a ticket of leave in 1821 and a conditional pardon in 1827 on the recommendation of Chief Justice Forbes, his wife Mrs Forbes, and Judge Stephen.[3] That William received such support from these prominent and respected citizens, especially from Mrs Forbes, is remarkable. Somehow, he must have come into sufficient contact with them that they could form the view that he was worthy of a pardon. A further nine children were born to Sophia and William with Henry being born on 17 July 1829 and dying on 13 March 1884 during a severe outbreak of typhoid fever in Sydney.[4]

Margaret Thomson Stobo[5] (known as ‘Maggie’) was aged 19 when she married Henry, aged 42, on 7 June 1871[6] at St James, King Street, Sydney. Maggie was born in Greenock, Scotland, in 1852 and was part of a large family; she died in 1892. [7] She came to NSW in 1854[8] with her mother Mary in order to join her father, Captain Robert Stobo.[9] Stobo was the Captain of an Illawarra Steam Navigation company (ISN) steamer William IV and he later became the ISN agent and harbour master at Kiama, NSW.[10] Together Maggie and Henry had six children: Halcyon Mary Spears (1872-1873),[11] Henry Stobo (1873-1897), Beatrice Sophia Yates (1876-1933), Robert Stobo (1878-1890), Irene Victoria (1880-1972)[12] and Frederick Stobo (1884-1916), born shortly before his father’s death.

Church Involvement

The Phillips family had a long association with St James King Street, maintaining a family pew there from 1833 until at least 1861 which, considering William only received a conditional pardon in 1827, is remarkable.[13] William’s funeral in 1860 was organised by Charles Beaver ‘undertaker, St James’ Church’ and in 1871, Henry was married there by Canon Allwood.[14] Henry did more than occupy pew No 86 at St James, however, for around 1846 and aged 17, he began to teach Sunday School, eventually becoming the Sunday School Superintendent. He took an active interest in Sunday Schools through his active participation in the Church of England Sunday School Institute.[15] At one Institute meeting, he advised his fellow teachers that ‘he found it a good plan of keeping up attention was to have the children ranged around him, and set them to find passages of Scripture’.[16] He also pointed out the ‘several advantages that arose from the teacher visiting at the residences of the children’ who were attending the Sunday School’. In addition, he suggested that ‘every member of the church might be serviceable in the cause of the Sunday-schools even though they were not mentally capacitated for being teachers.’[17] They might, he said, ‘inform the people in their neighbourhoods that a Sunday-school existed in the parish and urge the people to send their children there.’[18]

Professor John Smith (1821-1885): Theosophical Dabbler or Devotee?

John Smith (1821-1885), foundation professor of chemistry and experimental physics at the University of Sydney, was born on 12 December, 1821, at Peterculter, Aberdeenshire, Scotland, the son of Roderick Smith, blacksmith, and his wife Margaret, née Shier. From 1839 he studied at the Marischal College, Aberdeen (M.A., 1843; M.D., 1844). Smith arrived in Sydney on 8 September, 1852, on the Australian.[1]

There is a good deal of information available on Smith, but little work has been done on his philanthropic and religious views. An article from Sydney University, which understandably concentrates on his scientific work, briefly mentions his philanthropic interests but omits to make any mention at all of his religious commitments which were also an important feature of his life.[2]

The Australian Dictionary of Biography says of his religious views that ‘In the 1860s Smith served on the committees of several religious organizations’, by which is meant Christian organisations, and that

In January 1882 he had called at Bombay and joined the Indian section of the Theosophical Society, having been influenced by his wife’s spiritualism and the lectures of the theosophist Emma Hardinge Britten in Australia in 1878-79. In Europe in 1882-83 he experimented with the occult.[3]

This article’s religious emphasis falls on the last five years of Smith’s 63-year life and has little to say about his religious commitments during the previous 58 years. This is reflective of Jill Roe’s work which is mainly concerned with Smith’s interest in Theosophy[4] and, while not said overtly, she seems to want to paint Smith as a theological progressive moving from the strictures of a doctrinal Presbyterianism to Theosophy. For Roe, Smith’s encounter with Theosophy was about ‘religious progress’ and the ‘maintenance of true religion’.

The usual paradigm for recruits to spiritualism was one of a theological ‘progress’ which moved from a nineteenth-century disillusionment with the revelation-based approach of Christianity to the intuitive approach to religious knowledge of theosophy. The disillusionment with revelation was rooted in an uncertainty about the Bible, fed by the rise of biblical criticism, the theory of evolution and an increased moral sensitivity repulsed by various biblical events. The problem with this hinted assessment of Smith is that while there is clear evidence of his interest in theosophy there is no evidence to support a disillusionment in his Christian thought, a point which Roe concedes.[5] Roe equates Smith’s interest in theosophy with a desire for ‘religious progress’, but it could equally be a case of intellectual curiosity. For a Professor of Physics, the role and reputed powers of the masters in theosophy would raise serious questions about the nature of matter and spirit. Perhaps it is from a desire for ‘scientific progress’ rather than ‘religious progress’ that Smith’s chief motivation to understand spiritualism arose. That is not to say that Smith had no interest in what Theosophy might have to say about spiritual matters. Rather, it might be better to see Smith as, to use Malcolm Prentis’ expression, a ‘dabbler’[6] in Theosophy rather than a devotee. This article seeks to examine such a possibility. (more…)

William Briggs (1828 – 1910) and Charlotte Sarah neé Nicholson (1820-1879) Maitland Benevolent Society

William Briggs was born in 1828[1] in London, England, the third and youngest son of Thomas Briggs, a highly successful dressing case maker and general fine goods retailer of 27 Piccadilly, London,[2] and Elizabeth Nicholson. It appears that the success of Thomas in business permitted his son to be apprenticed as an attorney. William would have served at least five years as an articled clerk in a law office, possibly Seymour Chambers, Duke Street, Adelphi (St James’).[3] In 1853, he married his cousin Charlotte Sarah d’Argeavel neé Nicholson (1820-1879),[4] the daughter of Robert Dring Nicholson, a soldier, and Anne Elizabeth Perry. Charlotte was purported to be the widow of Vicomte Alexandre Eugene Gabriel d’Argeavel. When six months pregnant, Charlotte married the Vicomte in Boulogne, France, in October 1839 and she bore him three children: Alice (1840-1876), Eugenie (1842-1913) and Robert (1844-1913). In 1845, the viscountess separated from her husband and she and her children went to live with her parents in Jersey.

In 1852, Charlotte said she ‘observed in the papers an announcement of the death of her husband (who did not in fact die until 1877)’ and on July 4, 1853, she went through a marriage ceremony with William.[5] What is omitted from this account is that prior to this bigamous marriage a daughter Amy (1852-1919) was born to William and Charlotte in April of 1852. On July 28, 1853, two weeks after their ‘marriage’, William and Charlotte, with their children and Charlotte’s mother Anne Nicholson,[6] boarded the Windsor and sailed to the colony of NSW arriving in Sydney on November 2, 1853.[7] Why they decided to come to NSW is unknown, but perhaps they considered it prudent to remove themselves to a sphere where their past history was not known.

William applied for admission as a solicitor and proctor of the Supreme Court of NSW[8] and was admitted on December 31, 1853,[9] and commenced work as a solicitor in West Maitland in February of 1854.[10] In 1855, he was appointed clerk of petty sessions for the police district of Maitland.[11] During their time in Maitland, Charlotte gave birth to four sons: William (1854-1910), Hugh (1856-1929), Neville (1859-1859) and Alfred (1861-1933). Charlotte died in the February of 1879[12] and later that year, in November, William married Elizabeth Rourke (1837-1918),[13] a family friend and co-worker with Charlotte in charitable work.[14]

Maitland Benevolent Society

In 1885, some five years after Charlotte’s death and William’s marriage to Elizabeth, the Briggs left West Maitland and moved to Sydney. Upon the Briggs’ departure, the Committee of the Maitland Benevolent Society (MBS) expressed their

regret to record the loss (by removal to Sydney) of the valuable services of their late respected and energetic secretary Mr William Briggs, whose deep interest in the affairs of the Society, together with those of his estimable wife, from its very formation, contributed in a very great degree to raise it to its present important position.[15] (more…)

John Thomas Neale (1823-1897) and Hannah Maria Bull (1825-1911) Financial Philanthropists

John Thomas Neale died in Sydney in 1897 leaving an estate valued for probate at £804,945 ($12.2m current value)[1] and in his will he made significant bequests to his wife Hannah as well as to family members and others. He also left some £18,500 ($2.8m current value) to various charitable organisations. As significant as these charitable bequests were, they were far exceeded by those made by his wife. Some 14 years after John’s death, Hannah died with an estate valued for probate at £758,997 ($13.9m current value) and she left some £47,500 ($5.7m current value) to various charities and the remainder of her estate to family and friends.

Who were John and Hannah Neale?

John Thomas Neal was born at Denham Court, Campbelltown, NSW, in 1823 to John Neale (1897-1875) an overseer and later a carcass butcher, and his wife Sarah Lee (1799-1855). John Thomas was one of 14 children; 12 lived to adulthood and in 1843, at the time of the birth of his youngest sibling, 10 still lived in the family home. John Thomas, the second son, married Hannah Maria Bull (1825-1911) the daughter of John and Elizabeth Mary Bull of Bull’s Hill, Liverpool, in August 1843; she was 18 and John 20 and they were never able to have children. John died at his Potts Point home, Lugarno, in September 1897, aged 74[2] and Hannah died at Lugarno in March 1911, aged 86.[3]

Business Interests

John commenced building his fortune in the livestock trade following in his already wealthy father’s footsteps. Commencing initially in the Monaro district working on his father’s leased pastoral run Middlebank, he soon returned to Sydney to become a carcass butcher in his father’s business in Sussex Street.[4]