On 25 September 1890,[1] in his parish of Bong Bong in the Southern Highlands of NSW, the Rev William Ansdell Leech, an Anglican clergyman, formed a Ministering Children’s League (MCL) group from which the NSW Fresh Air League (FAL) would arise. Initially, the activity that gave rise to the FAL was Leech’s particular way of fulfilling the ideals of the MCL. It soon became apparent that providing holiday accommodation for poor children and families in a healthy mountainous environment was a ministry deserving of its own name.

William Ansdell Leech (1842-1895) was the eldest son of Rev John Leech, MA, of Cloonconra County Mayo, Ireland, and Mary nee Darley, daughter of William Darley of St John’s County Dublin.[2] Leech matriculated to Cambridge University in Lent of 1865 and was a Scholar at the University from 1866. He was admitted to Lincoln’s Inn on 6 November 1866, gained a BA in 1868, and was called to the Bar on 10 June 1870 as a Barrister-at-Law. Leech went on to be ordained deacon by the Bishop of Wellington, New Zealand (and appointed a curate of Palmerston North) in 1883, before being priested by the Bishop of Bathurst in St Andrew’s Cathedral, Sydney, in December of that same year.[3]

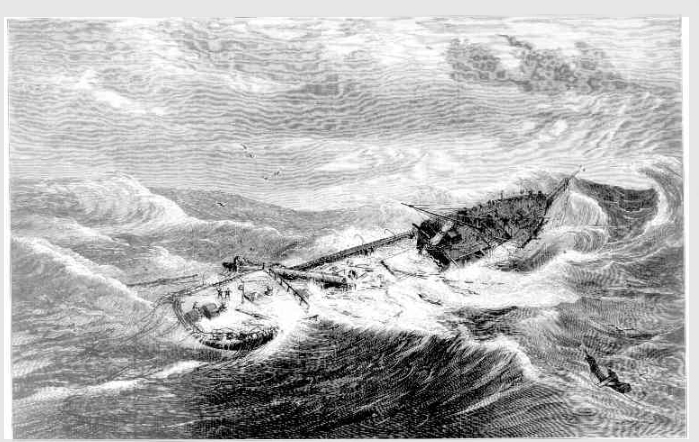

Travelling to New Zealand on the Dallam Tower

Leech’s first attempt to sail to New Zealand was not without incident for he travelled aboard the Dallam Tower which had left London on 11 May 1873, bound for Dunedin, New Zealand.[4] On 14 July, the ship met a ‘fearful hurricane’ and was dis-masted in latitude 46 degrees south and 70 degrees east. The vessel was at the mercy of the storm for some 14 hours after which the hurricane abated. Without a mast the ship was helpless, but after 11 days the Cape Clear, a cargo ship, came to their assistance and took off some of the Dallam Tower’s passengers who were in ‘a most forlorn and destitute condition. Their money, letters of credit and introduction, clothing and other necessaries gone.’[5] As one passenger remarked, they were fortunate not to have lost their lives:

But it was a mysterious Providence that sent the Cape Clear to our help. Had it not been for the distressing loss of two of their number we should never have seen her. One of the apprentices on the previous day had fallen from the rigging, and another in a noble but hopeless attempt to save him, went overboard after him. The ship delayed her course for several hours, while a boat was sent in a vain search for these poor fellows. Thus it was that she came up with us at the dawn of morning, otherwise they would have passed us in the night without seeing us.[6]

William also wrote an account that was as detailed as it was frightening, even though he was one of the small group that the Cape Clear was able to take on board.

Captain Landsborough readily took sixteen of us on board, all he could accommodate. Words can but poorly express the kindness and hospitality shown to us by the captain of the Cape Clear, and all under his authority and Mr Roydon Wilson, the sole passenger on board, who comforted us in our forlorn condition.[7]

He also appears to have organised a letter on behalf of some of the prominent passengers to the underwriters of the ship indicating their lives would have been lost were it not for various members of the crew who were specially named in their letter.[8]

Sydney, London and Return via New Zealand

The Cape Clear did not deposit the passengers it had taken off the Dallam Tower in New Zealand but in Sydney, arriving there on 21 August 1873. The remainder of the passengers who stayed on the Dallam Tower were disembarked on 20 August 1873 in Melbourne where the ship was to undergo repairs.[9] The intention of the shipping agent, Lorimore, Marwood and Rome, who were responsible for the Dallam Tower, was to accommodate the passengers in Melbourne and to organise their transport via the steamer Albion to their original destination of Dunedin.[10]

William, however, did not journey to Melbourne and then to New Zealand as the other passengers were to do. He had it in mind to return to England directly from Sydney and this plan would allow him a month to see Sydney and become familiar with it, and perhaps to become known to people there. In his account of being taken off the damaged ship and afforded accommodation on the Cape Clear, he praised the kindness of the captain, John Landsborough, and that of the Cape Clear’s one other passenger whom he mentions by name, Roydon Wilson.[11] As the Cape Clear was due to sail from Sydney to San Francisco with its load of 970 tons of coal, both Wilson and Leech decided to travel with it as the only two passengers. It left Sydney on 20 September 1873 and arrived in San Francisco on 21 November 1873.[12] From San Francisco, Leech had the choice of going by rail to New York, and then by ship to Liverpool, or to stay with the Cape Clear which was also Liverpool bound. If he took the rail option he could have been back in London before Christmas, but if he remained on board the Cape Clear he would not leave San Francisco until early January 1874, arriving in London around mid-May 1874.[13]

On his return to England, Leech worked as a barrister in London from 1874 until 1882.[14] He continued to work from his chambers at 3 Old Square which he had rented since 1872 but, in 1881, he moved to 25 Old Square.[15] Leaving London in 1882,[16] he returned to his earlier intention of travelling to New Zealand and this time he went via New York and then travelled across America by rail, arriving in Wellington in November 1882.[17] In February 1883, notice was given in St Paul’s Wellington that ‘Mr W Leech, formerly of London, and a barrister by profession, is a candidate for admission to Holy Orders at the next ordination to be held by the Bishop of the diocese.’[18] He had come to New Zealand with a ‘testimonial’ from the Church of Ireland Bishop of Kilmore, Elphin, and Ardagh, the very elderly John Richard Darley, to whom William was related.[19] He was ordained, ‘admitted to deacon’s orders’ on 18 February 1883[20] by the ‘Lord Bishop of Wellington’ the Right Rev O Hadfield[21] and, for the time being, became curate at Palmerston North.[22] His stay was short-lived as he left in August 1883 to go to Sydney.

Marriage

Mary Walker nee Alger (1837-1914) was the daughter of Richard Alger, a farmer, and his wife Sarah.[23] In about 1862, Mary married John Walker, a solicitor’s clerk,[24] and they had seven children (Alice Mary, Tom, one female and four male siblings).[25] Sometime in 1877 or earlier, Leech and Mary began a relationship cohabiting at 9 Royal Ave Chelsea, and on 10 February 1878, Mary gave birth to Laura with William Ansdell Leech designated as the father on both her birth certificate and baptism record.[26] On 3 October 1881, at the Register Office for the district of Chelsea, and not in a church, Mary Walker married William Ansdell Leech.[27] Presumably the timing of the marriage, well after Laura’s birth, was determined by John Walker’s death.[28] Sometime in late 1882, William left Mary and Laura in England and travelled alone to New Zealand, and some two and a half years passed before Mary and Laura joined William. In January 1885, Mary Leech arrived in Sydney with their seven-year-old daughter Laura (1878-1960) aboard the SS Liguria.[29] Some of the other of Mary’s English-born children, from her first marriage to John Walker, came independently to Australia, Alice Mary in 1886 and Thomas in 1884 or 1885.[30]

Why did Leech come to the colony of New Zealand and then New South Wales?

People came to the colonies for various reasons. Among those reasons were the opportunity for advancement, for a perceived health benefit, or to evade the consequences of ones actions at ‘home’. Leech may well have had only one of these reasons in mind as he boarded the Dallam Tower in 1873 bound for Dunedin, but perhaps he had all three in mind in 1882 as he headed back to New Zealand and then to Sydney.

Why would a newly qualified Barrister-in-law having taken chambers in 1872, a short time later in May 1873 decide to take a sea voyage to New Zealand? The most likely reason, given the subsequent concentration on his health, was that he had taken a sea voyage on medical advice to restore his health. It may be that he had in mind either the option of returning to England refreshed with improved health or of remaining in New Zealand and building a life there. His brush with death on the Dallam Tower, together with the loss of his ‘money, letters of credit and introduction, clothing and other necessaries’,[31] perhaps ensured he chose the option of returning to England irrespective of any improvement in health.

As to his reasons for his second trip to New Zealand and then to Sydney, it would appear that he had several. It seems that on this trip he intended to leave England permanently or at least for a considerable period of time. Leech, prior to his second trip to New Zealand in 1882, and unlike before his first ill-fated voyage, discontinued maintaining his barristers’ chambers in the Old Square in London. This action, together with his leaving his wife and daughter in England, is suggestive of the possibility that, depending on how things turned out in the colonies, he might not return to England.

The primary reason for William for coming to New Zealand and then to Sydney was probably still his health. It was publically said to be the reason for his leaving New Zealand so soon after his arrival. The position in Sydney had been offered to him in June, but he had refused the offer.[32] The later reconsideration of such a move was, he said, related to his health as a disappointed Palmerston North public was informed that ‘His health is not robust; and he hopes that by trying a change of air and scene it may improve’.[33] It was certainly, according to the medical wisdom of the day, a good reason to leave England and seek a better climate. William did have health issues that seem to have been a factor in his premature death. Given that Palmerston North had a temperate climate,[34] however, it does not appear to be a good reason to so quickly be, firstly, in discussions about leaving New Zealand a mere four months[35] after his ordination and then, secondly, at six months, to actually leave New Zealand for Sydney. The move to Sydney after such a short time in New Zealand would seem to indicate the possible existence of additional reasons to that of his poor health.

One such additional reason might have been that if he had wished to become a clergyman in England then Leech’s relationship with Mary and his fathering a child out of wedlock, if publically known, may have been an impediment to gaining ordination. Perhaps this is why he travelled to New Zealand where he thought his past would be unknown and where he could be ordained as a deacon. With his educational qualifications, family connections and a testimonial from the Bishop of Kilmore, Elphin, and Ardagh, Leech would appear as a gift to the New Zealand church. The New Zealand bishop who ordained him would have been keen to recruit men into the ministry for service in his diocese, and especially one who had the educational strengths and background that William possessed as a barrister-at-law and the son of a clergyman.

The move to Sydney may have been prompted by William’s discovery that even New Zealand was not remote enough to obscure his past. While his distant relative, the bishop of Kilmore, was probably unaware of William’s marital circumstances when he gave his testimonial, William’s cousin who was also called William Ansdell Leech, may have been more up to date with family news. This William, together with his wife and daughter, had arrived in New Zealand in 1879 settling at Tauranga which, like Palmerston North, is on the North Island of New Zealand.[36] Perhaps in light of this, William considered it a good idea to move to the colony of New South Wales where the origins of his marital situation would be less likely to be known and therefore not be an impediment to his advancement in the church and society.

There is, however, a further reason and perhaps it is the most significant one for his early departure from New Zealand and it relates to the issue of financial security. Blain refers to correspondence between two members of the Wellington diocese and it would appear that Leech was not being paid an adequate amount. Leech raised the matter with the bishop and ‘he received a reprimand as he had not experienced since he left school’. It was after this that he accepted an offer from Sydney that he had initially refused.[37] The Sydney parish was a more desirable location in terms of ministry and conditions if he intended to have his wife and daughter join him in Australia.

Sydney and the Blue Mountains

In August 1883, William moved to Sydney to become curate at Petersham/Marrickville, under the Rev Charles Baber. It was commented that though his stay in Palmerston North had been short it was sufficiently long to demonstrate his ‘devotion to his sacred calling and his genuine Christianity.’[38] With such an endorsement of his ministry it is unsurprising that on 28 December 1883, he was priested in St Andrews Cathedral, Sydney,[39] and then served as curate of Petersham (in charge of Marrickville) from 1883 until 1885, then he went to the Blue Mountains to St Aidan’s, Blackheath, where he served as ‘locum-tenens’ from 1885 to 1887. The Blackheath parish, at that time, included the churches at Katoomba and Mount Victoria.[40]

The Southern Highlands of New South Wales and the Fresh Air League

In 1888, Leech moved to the Southern Highlands of NSW and became the Vicar of Christ Church, Bong Bong, with Mount Ashley and Yarranga, from 1888 until 1895.[41] Under Leech’s leadership and from its first meeting in 1890, the Bong Bong MCL decided to take advantage of the local healthy climate by making its own contribution to the work of the MCL. This was done by providing ‘the sick and tired respectable poor of the metropolis, especially the women and children with a four weeks’ summer holiday.’[42] Leech enlisted the assistance of some Sydney ladies, principally Lady Darley[43] who was honorary secretary of the MCL, who collected sufficient funds to defray the railway charges, and the Bong Bong group took care of the costs of board and lodging. In 1891, at the end of its first year of operation, the work was deemed a success but Leech regretted that more sick children had not been able to be brought to enjoy a holiday. The chief difficulty had been the inability of this rural-based ministry to select suitable city residents who would benefit from the ‘fresh air’ of the Southern Highlands. This problem was solved with the appointment of a Sydney Committee of Ladies headed by Lady Darley which would select suitable applicants.[44]

Under the auspices of the MCL, Mr F Becke, an inmate of the old men’s asylum at Parramatta, stayed for six weeks at Mrs F Cunningham’s house near Fitzroy Falls. He wrote the following:

Yarrunga, 11th January, 1892.

Rev and Dear Sir,—

It was, I assure you, a great pleasure to me to meet at Mrs. F. Cunningham’s, Yarrunga, on the 6th instant, some of the children of the Ministering Children’s League, three of whom were under the charge of Mr. and Mrs. F. Cunningham, and four under that of Mrs. P. Harris, respectively both of Yarrunga. I further assure you that it was most gratifying to witness the happy, healthy condition of the children above named, and the manner in which they enjoyed themselves, I was twice in their company, and wished that I had been here on their arrival so that I could have been with them oftener. I understand that they left Yarrunga on Saturday last, 9th inst., on their return to Sydney after their enjoyable visit to the delightful and most healthful locality, which I have found so beneficial to my health, which was in a most precarious state when I arrived here to recoup it, under your most kind auspices on the 19th ultimo, and I can confidently assert that I have proved it to be the most invigorating, health restoring, climate and delightful resort for an invalid that I have ever visited, and I trust it may be my good fortune to again meet with the same happy children of the Ministering Children’s Society on some future festive season, should my life be spared.

Believe me, dear sir,

Yours truly and obliged P. BECKE (late Civil Service)

The Rev. W. A. Leech, M.A., Moss Vale.

In March 1892, Mary R Kendall, a member of the FAL ladies committee, took the opportunity of commenting on a recent publication by Dr Philip Muskett (1857-1909) who was a well-known and widely read publisher of books on health, particularly for children. She pointed out that what was advocated by Dr Muskett was already in operation in the Moss Vale area. Dr Muskett had written of the alarming rate of infant death where out of every three deaths occurring in Sydney, one was of an infant less than 12 months old. His remedy was the ‘formation of a mountain sanatorium to counteract the effects of the hot weather, usually so dangerous to infants.’[45] In that year, the FAL had already provided a respite holiday for over 60 people. They had, however, run out of funds and so had suspended their activity pending money being raised to develop a fund to support the work of the FAL.[46]

This fund raising was to take the form of a ball with his Excellency the Governor and Lady Jersey, as well as his Excellency Rear Admiral Lord and Lady Charles Scott, as patrons and involving the ‘social elite’ of Sydney. Lady Darley chaired the committee and she and her committee no doubt utilized their considerable social networks involving the wealthy, influential and the ‘who’s who’ and the ‘highest ranks of society’[47] in Sydney. The result was that the ball, despite the difficult financial times, was a great financial success. As the FAL was able to place people in respite at a cost of £2. 10s each in 1892, the £490 raised by the Ball meant that there was a now a fund that would enable the work of the FAL to continue even in the difficult financial circumstances of the 1890s.[48]

Sometimes the members of the Sydney ladies committee of the FAL would organize for children in whom they had a special interest to be sent to Bong Bong. At a monthly meeting of the Bong Bong FAL, Mr Leech reported that

Mrs. John See, had just recently sent up Barbara and Lilly Challenar, who were very delicate indeed and suffering from a heart complaint. They were staying at Mrs. Baxter’s farm at Wild’s Meadow, and when he visited them they said they had already felt much better by the change. Mrs. See had asked him to give a little personal supervision to the Misses Challenar, and without wishing to escape his share of visiting, he should feel glad if some of the associates would go and see them which, would probably have the effect of cheering them.[49]

By January 1893 in the Moss Vale area, the FAL had seven farm houses under the Rev W A Leech’s superintendence, whom it was said ‘had worked unsparingly for the success of the league since its formation’ and at Bowral, Glenbrook, and North Springwood there were comfortable cottage homes open for the reception of those sent under the scheme.[50]

William Ansdell Leech’s death

In November 1895, the Rev W A Leech, the founder of the FAL and a keen supporter of its expansion, died; he was only 53 years old.[51] Leech had been suffering from the ‘lung complaint’ of consumption from which he had been imperiling his health for ‘many years’,[52] and which may account for his deciding to accept a church position in a parish that enjoyed the ‘healthy air’ of the Southern Highlands of NSW. His leadership in the formation of the FAL and his dedication to the advancement of its cause could well have arisen from the belief, as was common in the nineteenth-century, that fresh air had a restorative effect on those suffering from consumption and that foul air was a source of consumption.[53] His death was a significant threat, indeed ‘very near its death blow’, to the continuance of the FAL as he had effectively been its treasurer, secretary, and committee.[54] The local MCL, encouraged strongly by Lady Darley, was keen that the FAL should be the success that ‘Mr Leech’s dying wish’ hoped it would be.[55] The Rev R S Willis, vice president of the BDMCL (Berrima District Ministering Children’s League) also encouraged its continuance and said that it would continue:

So long as we do not try to carry it on in too ambitious a scale, so long as we remember that it is a society belonging to children and not grown-up people, to be supported mainly by subscriptions and the work of the children themselves rather than by the subscriptions and the work of their parents …[56]

The challenge was met and people volunteered to fill the various roles and took local ownership of the FAL which was one of the reasons why the MCL and the FAL in the Southern Highlands commanded the support and lasted as long as it did.[57] The post-Leech plan, which proved so successful, was that their monthly meetings would be in the ‘form of work meetings, each lady undertaking to teach four children some useful work’ and a carpenter was also engaged to give lessons to the boys in carpentry.[58] The housing of poor families from the city for a ‘fresh air vacation’ also continued and a number of vigorous MCL groups were formed in the Southern Highlands; these groups were clearly the most active within the MCL FAL ministry. In the 1899 season, some 127 children, 115 women, and 11 men were sent to farm houses at Rooty Hill, Blackheath, Liverpool, Thirlmere, Mittagong, Bowral, Moss Vale, and Berrima’. Of these, some 28 people were funded and housed by the Berrima district group.[59]

Leech’s Unpaid Stipend

On the death of Leech, a significant amount of unpaid stipend was owed to him by his parish. At a community fete in 1896, there was a special stall with its proceeds dedicated to paying the arrears of the stipend to Mrs Leech. Remarkably, Sir Frederick Matthew Darley gave a cheque to the stall organizer for 10 guineas, approximately $2,000 the present day, which was a significant amount of money. Why was it that Sir Frederick gave the donation rather than Lady Darley who was the one involved with the FAL? And why was it so large a donation? It may simply be that Sir Frederick gave it on behalf of Lady Darley in appreciation for the dedicated service that the Rev W A Leech had given to the cause of the FAL. However, Leech and Sir Frederick were distantly related for Leech’s father was the Rev John Leech and he had married Mary Farren Darley whose father was a brother of Sir Frederick’s grandfather. This meant that William and Frederick were second cousins. This family connection could also explain why Lady Darley gave her strong support of the MCL’s Bong Bong branch and how it was that Leech easily enlisted the support of Lady Darley for the FAL at Bong Bong.

‘Beloved by all who knew him. His last words “God is good”’ were inscribed on his impressive grave of Italian marble whose construction had been organized by his wife at a cost of some £40.[60] Given his relatively short life of 53 years, with much of it marked by poor health, his last words were the confession of a man with a positive outlook on life. Leech’s motto from his family crest was ‘Virtute et valore’ – ‘The courage to do the right’. In his short life, he certainly showed courage and dedication through his innovative FAL. If setting it up was not really an example of doing the ‘right thing’ it certainly was doing a ‘good thing’, a reflection perhaps of his understanding of the character of God, and from which many poor families were to benefit.

Paul F Cooper

Research Fellow

Christ College, Sydney

The appropriate way to cite this article is as follows:

Paul F Cooper. William Ansdell Leech (1842-1895) and the Fresh Air League Philanthropy and Philanthropists in Australian Colonial History, 13/01/2024, available at colonialgivers.com/2024/01/13/ William-Ansdell-Leech-1842-1895-and-the-Fresh-Air-League

[1] Australian Town and Country Journal (Sydney, NSW), 4 Oct 1890, 16.

[2] William was born on 30 September 1842.

[3] Cable Anglican Database entry for W A Leech. The Daily Telegraph (Sydney, NSW), 31 Dec 1883, 1.

[4] Evening Star, Issue 3240, 9 July 1873, 2.

[5] Evening News (Sydney, NSW), 22 Aug 1873, 2.

[6] Evening News (Sydney, NSW), 22 Aug 1873, 3.

[7] SMH, 22 Aug 1873, 5.

[8] Empire (Sydney, NSW), 27 Aug 1873, 2. He designated himself as the first signatory ‘William Ansdell Leech, of 3, Old Square, Lincoln’s Inn, Barrister at Law.

[9] Leader (Melbourne, Vic), 23 Aug 1873, 15.

[10] The Age (Melbourne, Vic), 30 Aug 1873, 1.

[11] The mention of the passenger by name is a little unusual. As they continued on together at least to San Francisco they had perhaps developed a friendship.

[12] Daily Alta California vol 25, 8638, 22 Nov 1873; SMH, 22 Sept, 1873, 4; 25 Sept 1873, 4. He is Mr Leash on the passenger’s list

[13] Daily Alta California, Volume 26, Number 8681, 6 Jan 1874; Glasgow Herald May 19, 1874, 10730, 6.

[14] William’s date of return is unknown.

[15] Boyles Court Guides (1872-1882); to be found in the Bodleian Library, Oxford.

[16] Probably late September or early October 1882.

[17] He left Omaha by rail on 17th October 1882 and arrived in San Francisco on 21st October leaving San Francisco on the steamer City of New York arriving at Auckland on 13 Nov 1882.; Sacramento Daily Union, Volume 16, Number 50, 18 October 1882; Thames Star, Volume Xiii, Issue 4327, 13 Nov 1882, 2; Daily Telegraph (NZ), Issue 3540, 13 Nov 1882, 3.

[18] Manawatu Times, Volume VIII, Issue 187, 15 Feb 1883, 2. He arrived in New Zealand in November 1882 on the SS City of New York. Ashburton Guardian IV, 791, 13 Nov 1882, 2.

[19] Darley died in January 1884 aged 85; Stephen, Sir Leslie, ed. Dictionary of National Biography, 1921–1922. Volumes 1–22. London, England: Oxford University Press, 1921–1922, see article Darley, John Richard vol 5, 506; Leech, William Ansdell; Cable Anglican Database (Online) accessed 26/11/2023; Blain Biographical Directory of Anglican clergy in the South Pacific ordained before 1951. Edited by Michael Winston Blain and Robert Arthur Bruère, 2024.

[20] New Zealand Mail, Issue 577, 24 Feb 1883, 5.

[21] The Australian handbook (incorporating New Zealand, Fiji, and New Guinea) and shippers’ and importers’ directory. (1883), 564; June Starke. ‘Hadfield, Octavius’, Dictionary of New Zealand Biography, first published in 1990. Te Ara – the Encyclopedia of New Zealand, https://teara.govt.nz/en/biographies/1h2/hadfield-octavius (accessed 31 October 2023). Hadfield had suffered from chronic illness throughout his life which significantly impacted his ministry. This may have influenced his decision to ordain him deacon after such a short time. Ansdell also had impressive qualifications while the bishop had not been able to be ordained in England for a lack of a university degree.

[22] The New Zealand Gazette, 1883, 22 Feb 1883, 286.

[23] The date of birth is the best estimate given conflicting evidence.

[24] Thomas Walker’s birth certificate lists the father as John William Walker ‘Managing Clerk to a Solicitor’ 10 May 1867; his baptismal entry gives John’s profession as ‘office clerk’.

[25] Mary Leech Death Certificate NSW BDM 2313/1914

[26] Laura was baptised on 31 May 1878, with William Ansdell Leach (sic) as the father and Mary the mother. Baptismal Register of St Peter’s Regent Square. Their address was given as 36 Regent Square.

[27] William Ansdell Leech and Mary Walker, Marriage Registration 3 October 1881 Chelsea, Middlesex.

[28] No trace of John Walker has been able to be found despite extensive attempts to do so.

[29] Left England 11 December 1884. SMH, 28 Jan 1885, 8.

[30] The Blue Mountain Echo (NSW), 6 Feb 1914, 5; SMH, 7 Nov 1885, 3; Harland Of London, R. H. Bidwell, Master, Burthen 1695 Tons From the Port Of London To Sydney, New South Wales, 12 November 1886. https://marinersandships.com.au/; Southern Cross (Adelaide, SA), Fri 5 Sep 1919, 9; Daily Herald (Adelaide, SA),9 May 1917, 4.

[31] Evening News (Sydney, NSW), 22 Aug 1873, 2.

[32] Manawatu Times, Volume VIII, Issue 342, 21 Aug 1883, 2.

[33] Manawatu Standard, Volume 4, Issue 213, 13 Aug 1883, 2. Leech, William Ansdell Cable Anglican Database would suggest that financial troubles in the NZ church were also a factor.

[34] Palmerston North’s climate is temperate, with warm summer afternoon temperatures of 20 – 22 °C (72 °F) in summer and 12 °C (54 °F) in winter. On average temperatures rise above 25 °C (77 °F) on 20 days of the year. Annual rainfall is approximately 960 mm (37.8 in) with rain occurring approximately 5% of the time. There are on average 200 rain-free days each year.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Palmerston_North# [accessed 14/11/2023]

[35] Manawatu Times, Volume VIII, Issue 342, 21 Aug 1883, 2.

[36] On board the Waikato leaving England on July 30, 1879; Auckland Star, Volume X, Issue 2957, 24 Sep 1879, 2; Bay Of Plenty Times, Volume XLVIII, Issue 7416, 27 May 1920, 2.

[37] Blain Biographical Directory of Anglican clergy in the South Pacific ordained before 1951, (Ed Michael Winston Blaine and Peter Arthur Brepe (2024) [accessed 26/11/2023].

[38] Manawatu Standard, Volume 4, Issue 213, 13 August 1883, 2.

[39] The Daily Telegraph (Sydney, NSW), 31 Dec 1883, 1.

[40] SMH, 5 Jan 1887, 3; The Daily Telegraph (Sydney, NSW), 22 Dec 1887, 5; The Blue Mountain Echo (NSW), 6 Feb 1914, 5.

[41] 6 Jan 1888. SMH, 7 Jan 1888, 12.

[42] SMH, 27 Feb 1893, 4.

[43] Leech and Lady Darley were acquainted as Leech had been ministering at Katoomba he would have met her at his church services when she vacationed at Katoomba December 1887-March 1888 and later again in 1889 at the Katoomba Anglican Church Fete which Lady Darley opened.; The Australasian (Melbourne, Vic), 10 Mar 1888, 10; SMH, 15 Nov 1887, 7.

[44] The Sydney Mail and New South Wales Advertiser (NSW), 10 Oct 1891, 832.

[45] SMH, 21 Mar 1892, 5.

[46] Australian Star (Sydney, NSW), 22 Mar 1892, 3.

[47] Albury Banner and Wodonga Express (NSW), 13 May 1892, 15.

[48] SMH, 27 Feb 1893, 4; 2 July 1892, 9.

[49] Bowral Free Press and Berrima District Intelligencer (NSW), 2 Jul 1892, 2. John See was, at this time, Colonial Treasurer in the third Dibbs ministry.

[50] SMH, 16 Jan 1893, 7.

[51] 21 November 1895. Bowral Free Press and Berrima District Intelligencer (NSW), 27 Nov 1895, 4.

[52] William Ansdell Leech, Death Certificate, NSW BDM 21 November 1895. That his death was actually due to Consumption was stated in one obituary. The Scrutineer and Berrima District Press (NSW), 23 Nov 1895, 4.

[53] Thomas Dormandy, White Death – A history of Tuberculosis, (New York; New York University Press, 2000), 43-44.

[54] Scrutineer and Berrima District Press (NSW), 7 Oct 1896, 2.

[55] Scrutineer and Berrima District Press (NSW), 7 Mar 1896, 2.

[56] Scrutineer and Berrima District Press (NSW), 7 Mar 1896, 2.

[57] Scrutineer and Berrima District Press (NSW), 7 Oct 1896, 2.

[58] Scrutineer and Berrima District Press (NSW), 7 Mar 1896, 2.

[59] SMH, 6 Oct 1899, 3.

[60] The Scrutineer and Berrima District Press (NSW), 3 Oct 1896, 2.