Home » Posts tagged 'history'

Tag Archives: history

Thomas Rothwell and the Sydney General Poor Relief Fund

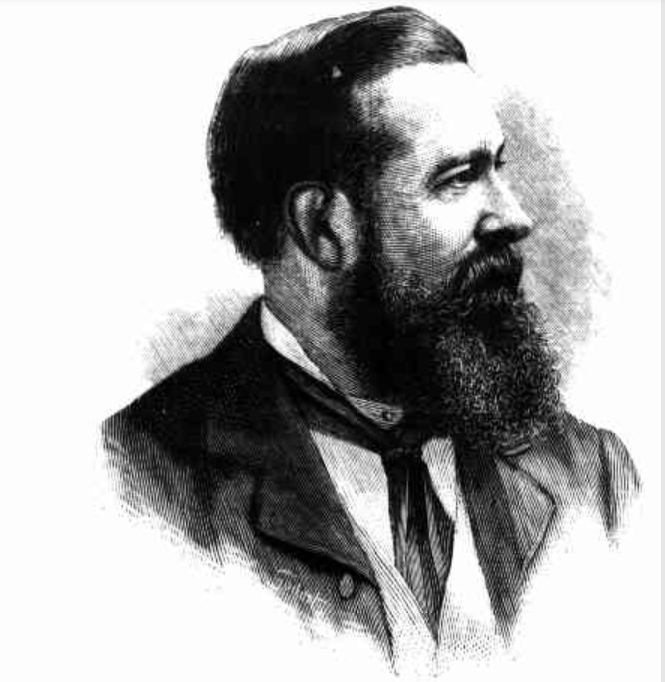

The Sydney General Poor Relief Fund (SGPRF) was so named to indicate its purpose. In the period just prior to World War I, it was promoted so that the poor of Sydney might enjoy the sympathy and some financial support of those who were better off. It was, however, a fake charity enriching and providing not for the poor but for an unscrupulous ‘con man’. Not all involved with charity were dishonest. Some who worked as fundraisers for the so-called charity were as duped as the general public.

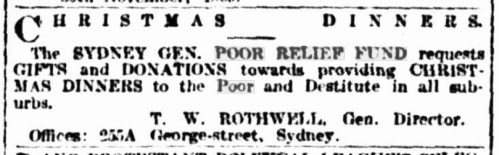

The Fund was first mentioned in the Sydney Morning Herald 22 November 1909 when a notice, designed to tug on the heartstrings of the sympathetic, was published. It sought gifts and donations towards providing Christmas dinners to the poor and destitute:[1]

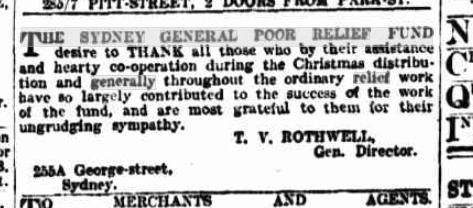

And this was followed with an after-Christmas thank-you note for the support the Fund had received, and it hinted about the support it had received for its more general relief program:[2]

Around this time, other concerts were organized by musicians who gave of their time and talents, and the money raised through ticket sales was given to the SGPRF. One such concert was held in the Balmain Town Hall in 1909 under the patronage of the Mayor and Mayoress of Balmain and was organized by Miss B Elvena Hurburgh, a piano teacher,[3] who went on to organize further fundraising concerts for the SGPRF. With increasing attendance, her concert was moved to the Sydney Town Hall with musicians giving of their services for the event. It was so well supported, by both musicians and the public, that it became an ‘annual’ event, providing further funds for the SGPRF up until 1914.[4] Other musicians organized their own concerts for the SGPRF like the piano concert given by Aaron Solomons, with assistance from other musicians, in the YMCA in 1909.[5] Another successful event was the harbour excursion and concert organized by Mrs Haffenden-Smith, assisted by her pupils, which was held aboard the Lady Northcote in 1910.[6]

(more…)Walter Vincent: Funds, Fatigue and Fraud – an aspect of charity in nineteenth-century NSW

Walter Vincent alias Brown was a member of the opportunistic profession of the sweet-talking donation fraudster. He presented himself as a genuine collector of subscriptions for various charities, but he was not.

Obtaining funding for the work of the various nineteenth-century philanthropic organisations was always a challenge. There was little government financial assistance available, and the various charitable organisations were dependent upon the generosity of the public for financial support. To gain that support, the many charities that wished to collect money from the public engaged in a number of activities and strategies. Prominent among their activities was the public annual meeting, often chaired by a socially important person, where the activities of the organisation were reported and supportive resolutions passed. At the meeting, someone, usually the committee secretary, would read a report detailing what had been achieved in the past year, often giving encouraging examples of success and underlining the difficulty of the task which the charity had undertaken. Such reporting made the committee that ran the charity accountable to the public and to its subscribers. It also showed what had been achieved through public financial support, educated the community on the continuing need for the charity, and gave hope for success in the future, so that there might be continued interest and increased financial support given by individuals. These meetings were often widely reported in detail by the press, which devoted considerable space to them.

During the 1890s through to the first decade of the 1900s, the colonies of Australia experienced a severe economic depression. Businesses reported a slowness in trade, a drop in profits, the need to shed workers and in the case of many, through indebtedness and an inability to service loans, to declare bankruptcy. On the personal front, and as a result of reduced income, this meant less food on the table and less access to medical assistance if needed. There was an increase in unemployment as businesses, both large and small, sought to reduce expenditure in an attempt to survive the times.

(more…)William Henry Millwood Haselhurst (1842-1917) gold miner

William Henry Millwood Haselhurst (1842-1917) was the son of Samuel Haselhurst (1795-1858) a gold miner[1] and Elizabeth Ann nee Atkins, then later Hosken, (1810-1890).[2] He was born at Lane Cove River near Sydney in February 1842, and at three years of age he was taken by his parents to Adelaide and then to the Burra Burra Copper mines in South Australia.

In 1852, the family moved to Bendigo, Victoria, where Samuel was involved in gold mining. This experience introduced William to what was to be his main interest in life – gold. He told the following story about himself:

In 1853, I was a boy of eleven years of age, living at Mount Korong, near what is now known as Wedderburn. One morning I was washing dirt in a tub at an old mullock heap in the eternal quest for gold. I might mention that the tub was made of an old flour barrel, and that our flour was imported from Valparaiso. My young brother was working with me, and we were intently engaged in our work when a company of the licence-hunters came along. The official stood and looked at me, then the sergeant gave the order. “March him off.” So I was marched off to the camp and charged with not having a licence. They evidently thought me trustworthy, because they allowed me outside the tent. For my dinner they gave me dumpling and sugar. In the afternoon my father called to interview the commissioner, who concluded I was too young to be compelled to have a licence, I was let off. Young as I was then, I remember that I fossicked out of a drive at the bottom of an abandoned shaft a nugget that weighed 3 oz. So perhaps the sergeant was right in thinking I should have had a licence.[3]

(more…)George William Barker (1826-1897) Wesleyan, Baker and ‘no idler in his Lord’s vineyard’

George William Barker was born in London on 5 July 1826, the son of George Barker (1803-1878) a musical instrument maker and Sarah Ann Craddock (1804-1887).[1] He came to Sydney on the Spartan with his parents, three sisters, Mary Ann, Sarah and Emma, and his younger brother, William. They arrived on 31 January 1838 after a voyage of some five months.[2] George’s uncles, Thomas (1799-1875) and James (1797–1861) Barker had arrived in the colony in 1822, some 15 years before, with Thomas[3] working as a clerk for John Dickson (1744-1843) a flour miller.[4] George was educated at Dr Fullerton’s School, Windsor, the King’s School, Parramatta, and the Grammar School Sydney.

Initial Business Involvement

After school and for some time, George partnered with his father as a grocer and corn dealer, in George Street Parramatta. In December 1847,[5] the public was advised that George was leaving the partnership.[6] So it was that in 1848, attracted by the business opportunities afforded by the development of Port Phillip and perhaps with a sense of adventure, he travelled overland with several friends for some 8 weeks to the Geelong area where he settled and ‘found a position in a store’.[7]

Family and Faith

It would appear that the move to the Geelong area was quickly crowned with success for George was soon able to marry. A friend recalled that “soon after a certain young lady went down to Melbourne from Parramatta, and Master George obtaining a week’s holiday started also for Melbourne, and at the end of the week returned with Mrs. Barker.”[8] In 1849 in Melbourne, George had married Eliza Hunt the daughter of Richard Hunt, a saddler and Lydia nee Barber.[9] Eliza was born in the Parramatta area and was known to George before travelling to Geelong.[10] They were to have six children: Sarah Elizabeth (1850-1851), Thomas Richard (1854-1860), Edwin George (1856-1918), Emily Eliza (1858-1931), Alice Maude (1863-1945) and Florence (1865-1867).

The Hunt family were involved with the Parramatta Wesleyan church and while the Barkers were involved with the Presbyterian Church in Parramatta,[11] George is only ever found associated with the Wesleyan Church. According to the Rev Joseph Oram, Barker became a member of the Wesleyan Church at Parramatta before he went to Geelong having been converted ‘during a religious festival when the Rev’s John Watsford and William Moore were brought to Christ’.[12] Watsford was converted at a prayer meeting run by Daniel Draper when he was 18 years old[13] so this would place Barker’s conversion in 1838 when he was around 12 years old.

(more…)Lady Lucy Forrest Darley (1839-1913), social position, charity and a glass of champagne

Lady Lucy Forrest Darley nee Brown(e) (1839-1913)[1] was born in Melbourne, the sixth daughter of Sylvester John Brown(e) (1791-1864) and Eliza Angell Alexander (1803-1889). On 13 December 1860, she was married in London to Frederick Matthew Darley, the eldest son of Henry Darley of Wingfield, Wicklow, Ireland.[2]

On 18 January 1862, she and her husband and a servant left Plymouth on the Swiftsure and arrived in Hobson’s Bay (Melbourne) on 19 April 1862. Six weeks later, on 1 June 1862, Frederick was admitted to the New South Wales bar on the nomination of John Plunkett QC.[3]

Lucy was to have six daughters and two sons. Henry Sylvester (1864-1917), Olivia Lucy Annette (1865-1951), Corientia Louise Alice (1865-1951), Lillian Constance (1867-1889), unnamed female (1868-1868), Cecil Bertram (1871-1956), Lucy Katherine (1872-1930) and Frederica Sylvia Kilgour (1876-1958). She sadly experienced the loss of one daughter at birth in 1868 and another daughter, Lillian, died from typhoid in 1889 when she was 22 years old.[4]

Lady Darley was active in charitable and philanthropic work and was a founder of the Fresh Air League, and one of the first members and the first president of the District Nursing Association. She also helped to form the Ministering Children’s League in Sydney, was keenly interested in the School of Industry, the Mothers Union, the Queen’s Fund as well President of the Working and Factory Girls Club and of the ladies committee of the Boys Brigade.[5]

She had gone to live with her husband in London in 1909 and died there in 1913. Her obituary in the Sydney Morning Herald noted that, during the time Sir Frederick Darley was Lieutenant Governor of New South Wales (NSW), Lady Darley gave her hearty sympathy and support to many charitable and philanthropic objects.[6] One might gain the impression from this statement that her charitable and philanthropic efforts were coincident with her husband occupying the role of Lieutenant Governor of NSW. In other words, it could be suggested that her involvement and philanthropic interest arose largely from her social obligations as the wife of the Lieutenant Governor. Was this a fair summary of Lady Darley’s charitable efforts?

(more…)William Ansdell Leech (1842-1895) and the Fresh Air League

On 25 September 1890,[1] in his parish of Bong Bong in the Southern Highlands of NSW, the Rev William Ansdell Leech, an Anglican clergyman, formed a Ministering Children’s League (MCL) group from which the NSW Fresh Air League (FAL) would arise. Initially, the activity that gave rise to the FAL was Leech’s particular way of fulfilling the ideals of the MCL. It soon became apparent that providing holiday accommodation for poor children and families in a healthy mountainous environment was a ministry deserving of its own name.

William Ansdell Leech (1842-1895) was the eldest son of Rev John Leech, MA, of Cloonconra County Mayo, Ireland, and Mary nee Darley, daughter of William Darley of St John’s County Dublin.[2] Leech matriculated to Cambridge University in Lent of 1865 and was a Scholar at the University from 1866. He was admitted to Lincoln’s Inn on 6 November 1866, gained a BA in 1868, and was called to the Bar on 10 June 1870 as a Barrister-at-Law. Leech went on to be ordained deacon by the Bishop of Wellington, New Zealand (and appointed a curate of Palmerston North) in 1883, before being priested by the Bishop of Bathurst in St Andrew’s Cathedral, Sydney, in December of that same year.[3]

Travelling to New Zealand on the Dallam Tower

Leech’s first attempt to sail to New Zealand was not without incident for he travelled aboard the Dallam Tower which had left London on 11 May 1873, bound for Dunedin, New Zealand.[4] On 14 July, the ship met a ‘fearful hurricane’ and was dis-masted in latitude 46 degrees south and 70 degrees east. The vessel was at the mercy of the storm for some 14 hours after which the hurricane abated. Without a mast the ship was helpless, but after 11 days the Cape Clear, a cargo ship, came to their assistance and took off some of the Dallam Tower’s passengers who were in ‘a most forlorn and destitute condition. Their money, letters of credit and introduction, clothing and other necessaries gone.’[5] As one passenger remarked, they were fortunate not to have lost their lives:

But it was a mysterious Providence that sent the Cape Clear to our help. Had it not been for the distressing loss of two of their number we should never have seen her. One of the apprentices on the previous day had fallen from the rigging, and another in a noble but hopeless attempt to save him, went overboard after him. The ship delayed her course for several hours, while a boat was sent in a vain search for these poor fellows. Thus it was that she came up with us at the dawn of morning, otherwise they would have passed us in the night without seeing us.[6]

(more…)