Lady Lucy Forrest Darley nee Brown(e) (1839-1913)[1] was born in Melbourne, the sixth daughter of Sylvester John Brown(e) (1791-1864) and Eliza Angell Alexander (1803-1889). On 13 December 1860, she was married in London to Frederick Matthew Darley, the eldest son of Henry Darley of Wingfield, Wicklow, Ireland.[2]

On 18 January 1862, she and her husband and a servant left Plymouth on the Swiftsure and arrived in Hobson’s Bay (Melbourne) on 19 April 1862. Six weeks later, on 1 June 1862, Frederick was admitted to the New South Wales bar on the nomination of John Plunkett QC.[3]

Lucy was to have six daughters and two sons. Henry Sylvester (1864-1917), Olivia Lucy Annette (1865-1951), Corientia Louise Alice (1865-1951), Lillian Constance (1867-1889), unnamed female (1868-1868), Cecil Bertram (1871-1956), Lucy Katherine (1872-1930) and Frederica Sylvia Kilgour (1876-1958). She sadly experienced the loss of one daughter at birth in 1868 and another daughter, Lillian, died from typhoid in 1889 when she was 22 years old.[4]

Lady Darley was active in charitable and philanthropic work and was a founder of the Fresh Air League, and one of the first members and the first president of the District Nursing Association. She also helped to form the Ministering Children’s League in Sydney, was keenly interested in the School of Industry, the Mothers Union, the Queen’s Fund as well President of the Working and Factory Girls Club and of the ladies committee of the Boys Brigade.[5]

She had gone to live with her husband in London in 1909 and died there in 1913. Her obituary in the Sydney Morning Herald noted that, during the time Sir Frederick Darley was Lieutenant Governor of New South Wales (NSW), Lady Darley gave her hearty sympathy and support to many charitable and philanthropic objects.[6] One might gain the impression from this statement that her charitable and philanthropic efforts were coincident with her husband occupying the role of Lieutenant Governor of NSW. In other words, it could be suggested that her involvement and philanthropic interest arose largely from her social obligations as the wife of the Lieutenant Governor. Was this a fair summary of Lady Darley’s charitable efforts?

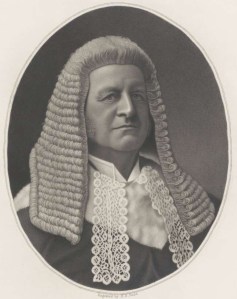

Lucy Darley’s last child was born in 1876 at which time her family consisted of children aged 12, 11 year old twins, 5, 4 and a newborn and though she would have had assistance, she would have been a very busy mother in the 1870s and well into the 1880s. So it is not surprising that the first mention of her in the social events recorded in the newspapers of the day was not until 1879 and it is not until the early to mid-1880s onwards, when her daughters were in their late teens, that she is mentioned with any regularity in the social pages of the newspaper.[7] From that time on, Lucy exercised publically the significant and prominent position in Sydney society that she held, a position that was largely due to her husband’s social status. At various times he was a prominent Barrister, Member of Parliament, Chief Justice and Lieutenant Governor. Frederick was made a Knight Commander of the Order of St Michael and St George in 1887 and a Knight Grand Cross of the same order on 6 May 1901. He was appointed Lieutenant Governor of NSW following Sir Alfred Stephen’s resignation on 27 April 1891. He acted as Governor on seven occasions: 2 March 1893 to 29 May 1893, 15 March 1895 to 21 November 1895, 22 November 1897 to 22 January 1898, 5 March 1899 to 18 May 1899, 24 January 1900 to 9 March 1900, 1 November 1900 to 27 May 1902, and 7 June 1905 to 29 December 1905. As Governor of NSW, he took a leading role in the Federation celebrations during 1900-01.[8]

It is certainly true that the vice-regal role of her husband carried with it certain social and societal obligations. Lady Darley’s life in the period 1891-1905 seems like an almost endless parade of garden parties, balls, dinners and the opening of fetes and exhibitions, not to mention her entertaining of important guests to the Colony at her home Quambi in Woollahra and Lillianfels in Katoomba. She was said to be ‘indefatigable in her official duty’,[9] and appeared to have filled the vice-regal consort role admirably by being a capable hostess and conversationalist. She was a popular society leader with an ‘exceptionally fine presence’,[10] and ‘charms of beauty and grace’ to which was added a ‘contralto voice of quality’.[11] With such social and societal expectations also came the community expectation of Lady Darley having a role in the female-dominated part of the charity and philanthropic sector.

It would have been possible to meet such obligations with minimal effort by becoming a patroness[12] or a titular president of various philanthropic causes and by attending their fund-raising activities, fetes and balls. To assume, as she did, such roles would have been sufficient for Lady Darley to have been thought to have fulfilled the social duty of a woman of her social stature.

Some charitable efforts by Lady Darley consisted of simply opening a bazaar and of saying the ‘right’ thing, commending the workers for their efforts as she did at a fete to raise funds for the Consumptive Home in 1905. On that occasion, she said:

It has given me very much pleasure to come here this afternoon to open this fete. There can be few charities in Sydney more worthy of support than that which does so much to resist the terrible disease of consumption. I am glad to see that of the 51 cases of disease received into the home last year no less than 30 were arrested, and only one case proved fatal. This grand result reflects much credit on those who so willingly give their services to this institution.[13]

Or, on another occasion at the YMCA building in Sydney, she opened a cake fair in aid of the Infants’ Home at Ashfield.[14] Travelling further afield, at Bulli she opened a cottage hospital and told the assembled crowd ‘that she felt confident that the institution would be a means of alleviating pain and helping many families out of trouble and sorrow.’ Then, in a skilful mix of appeal to local community pride, piety, and practicality, she said:

She had greatly enjoyed her trip down from Sydney, the scenery along the route being extremely beautiful. The hospital was in a lovely situation; its surroundings being delightful, and she hoped it would, with God’s blessing prove beneficial to all who might seek help in it …[15]

Her reputation as a gracious, encouraging and accomplished diplomatic public figure was well deserved and it is not hard to understand why she was popular.

Other of her charitable causes, however, required more of her time and effort than opening of fetes and hospitals. The Queens Jubilee Fund and the Women’s Industry Exhibition, the Ministering Children’s League[16] and Fresh Air League[17] were examples of where she was either an active member of the committee, Vice-president or President. In the case of the Fresh Air League, she used her social network and contacts to organise, with a committee of prominent ladies, a ball which was attended by the ‘Who’s who’ of Sydney and which, in difficult financial times, raised a considerable sum of money.

It would appear that the Sydney Medical Mission was also one such organisation where she went beyond a casual attendance at an event to a higher level of effort, commitment, and personal involvement. The Mission, established in 1900, sought to provide some medical care for those who could not access out-patient departments of hospitals and in its service covered Redfern, Alexandria, Camperdown, Erskineville, Paddington and Glebe. In May 1905, she presided over a meeting of the Mission at James Fairfax’s house and held a further meeting later in the year in her own home. [18] On that occasion she was said to ‘take a very lively interest in this good work’;[19] she presided over its annual meeting in 1907.[20]

More than supporting a charity though her attendance or presence on an organising committee, she was not averse to using her social contacts and position for more than encouraging society people to attend a ball. In 1880, she was part of a group to visit the Colonial Secretary on behalf of Ashfield Infant’s Home. The Sydney Punch reported it this way:

A deputation of ladies connected with the Infants Home, Ashfield, consisting of Mrs. Professor Smith, Mrs. Barrister Darley, Mrs. Upper House Docker, and Mrs. Legislative Council Moore, waited on the Colonial Secretary a few days ago to ask for a grant in aid of the institution they represented. Sir Henry was so overpowered by emotion at such a galaxy of beauty and intellect, that for some moments he was lost for words to express his feelings, at length he promised to take the matter into consideration.[21]

[Mr. Punch desires to give this deputation of ladies his warmest support, and trusts the venerable veteran, Sir Henry, will prove his gallantry by at once acceding to so thorough a request backed up by so fair a bevy of ladies. The cause is deserving of everyone’s assistance.][22]

With less humour, but more accuracy, the Sydney Mail reported:

A deputation of ladies connected with the Infants’ Home, Ashfield, consisting of Mrs Professor Smith, Mrs F M Darley, Mrs W Docker, and Mrs Henry Moore, waited on the Colonial Secretary on Thursday to ask for a grant in aid of the institution they represent. Sir Henry Parkes promised to take the matter into consideration.[23]

In 1888, she was again using her influence to move the Colonial Secretary, Sir Henry Parkes, to provide a solution to the plight of a woman and her daughter who had come from China to join her husband. They were seeking passage from Sydney to Hobart but were under threat of being forcibly returned to China. It was a time of agitation about Chinese immigration and there were strict laws which bound shipping companies with restrictions on the number of Chinese they could land at any given port in Australia. Lady Darley, in the company of Mrs M H Stephen, went to see Parkes to urge him to let Mrs Ah Moy and her daughter land in Sydney so they could transit to Tasmania.[24] Fortunately for Mrs Ah Moy it appears that Lady Darley and Mrs Stephen were very persuasive and later Mr Ah Moy expressed, through a telegram to Quong Tart, his sincere thanks to them for speaking on his wife’s behalf.[25]

Given Lady Darley’s intervention it is not surprising that in 1893 she was requested to lay the foundation stone of a new Chinese Church in conjunction with the mission of the Presbyterian Church. The building was in Foster Street off Campbell Street near Belmore Park. To mark the occasion, Missionary John Young Wai presented a New Testament in Chinese to Lady Darley as well as a knitted screen made by the Chinese women. While Lady Darley may have been asked simply because she was the Lieutenant Governor’s wife, the cordiality of the accounts of the event may also be due to the fact that Lady Darley’s intervention on behalf of Mrs Ah Moy had not been forgotten within the Chinese community.[26] Indeed, two years later she was again invited to assist the Chinese Church by opening a Missions Exhibition whose proceeds were to help pay off the debt on the Church.[27] She accepted the invitation and while opening the exhibition stated that:

She remembered with great pleasure the fact that she had laid the foundation stone of the Chinese Presbyterian Church … and her pleasure was heightened that day when she heard of the result of the work, and the interest being taken in the Presbyterian Chinese Mission. [28]

These were perhaps just the expected words for such an occasion, but on the other hand there is a note of sympathy in Lady Darley’s words and presence.

As was appropriate for a vice regal person, Lady Darley also bridged the Protestant/ Catholic divide where, with the notable exception of the Benevolent Society, most of the philanthropic/ charitable efforts were largely supported and organised by members of their respective faith group. Lady Darley, even before her husband assumed vice regal duties, attended and helped organise both and this was greatly appreciated by the Catholics, especially her involvement in the Magdalene House at Tempe.[29] She was dubbed by the Freeman’s Journal ‘the friend of the Good Samaritan nuns’[30] and on one visit to Tempe she said,

Everyone, she was sure, was struck’ as she was by the tenderness and affection of the Sisters for those who had come under their care. It was a wonderful work in which the Sisters were engaged. It was one of the most admirable works that could possibly be undertaken, and to succeed as they had done and were doing, the Sisters must have a singular blessing from God. (Applause.) Her own share in this work was so very small that she felt overwhelmed by a sense of unworthiness when she heard herself praised just now. It was in her power to do but little, but she hoped God would enable her to do something more in the future than she had been able to do in the past. (Applause.) It was quite true that she took the deepest interest in works of charity, especially those numerous works connected with the Catholic Church, and of which she had seen so much during the past few years. (Applause.) She had now great pleasure in asking the Rev. Mother to accept the handsome cheque handed in by the ball committee.[31]

In all of her personal charitable and philanthropic activity, with her ‘unfailing sympathy with charitable movements’,[32] perhaps her best contribution was in the leadership she gave in harnessing the charitable instincts of others in the causes she promoted.

In the words of the journalist, Mary Salmon:

The late Lady Darley was the most loved committee woman that Sydney has ever known. Her presence was like a glass of champagne at a dinner party. It put spirit and enthusiasm into even a dull cause. She was a born leader, and yet there was nothing harsh and dictatorial about her leadership. It was rather that of a vigorous comrade, who set the pace and marched shoulder to shoulder with others, even the weakest making an effort to keep up. There was no “Impossible” in Lady Darley’s mind when movements for others good were suggested. She picked up and made the very best of other ideas, as well as ventilating her own.[33]

Lady Lucy Darley, was a lady of unfailing sympathy for charitable movements which was evident before her husband became Lieutenant Governor of NSW in 1891, but undoubtedly that appointment enhanced her opportunities to exercise charitable work. Her sympathy was shown by her use of her considerable social standing to gain the support of others for her charitable interests; by her involvement and intervention, and her willingness to initiate and serve in governance roles within various philanthropic works, and perhaps best of all was her leadership. She was a born leader, and was ‘like a glass of champagne at a dinner party’, for her irrepressible presence enthused others in their charitable endeavours.

Paul F Cooper

Research Fellow

Christ College, Sydney

The appropriate way to cite this article is as follows:

Paul F Cooper Lady Lucy Forrest Darley (1839-1913), social position, charity and a glass of champagne, Philanthropy and Philanthropists in Australian Colonial History,15/4/2024 available at Colonialgivers.com/2024/4/15 lady-lucy-forrest-darley-1839-1913-social-position-charity-and-a-glass-of-champagne

[1] Sydney Morning Herald (SMH), 9 April 1913, 16.

[2] Argus 18 February 1861, 4.

[3] SMH, 3 Jun 1862, 5.

[4] SMH, 22 Apr 1889, 1;The Australian Star (Sydney, NSW), 22 Apr 1889, 6. Some of the Easter military exercises, were suspended in recognition that Miss Darley lay very ill in the Darley residence which was not far from the site of the exercises.

[5] The Sydney Mail and New South Wales Advertiser (NSW), 30 Mar 1895, 643.

[6] SMH, 9 April 1913, 16.

[7] SMH, 16 Oct 1879, 6; 14 Jan 1880,2; Sydney Mail and New South Wales Advertiser, 28 Feb 1885, 458; Daily Telegraph, 27 April 1876, 5.

[8] Frederick Matthew Darley, NSW State Archives Collection https://researchdata.edu.au/frederick-matthew-darley/145486 [accessed 1/10/2023; https://www.parliament.nsw.gov.au/members/Pages/member-details.aspx?pk=627 [accessed 7/10/2023] Photo http://nla.gov.au/nla.obj-136059271

[9] The Daily Telegraph (Sydney, NSW), 3 Aug 1895, 10.

[10] Sydney Mail and New South Wales Advertiser (NSW), 30 March 1895, 643.

[11] The Daily Telegraph (Sydney, NSW), 9 Apr 1913, 10.

[12] As she was of the Ladies Swimming Club. The Australian Star (Sydney, NSW), 1 Dec 1905, 2.

[13] SMH, 16 Dec 1905, 14.

[14] Evening News (Sydney, NSW), 5 May 1893, 6.

[15] Illawarra Mercury (Wollongong, NSW), 23 May 1893, 2.

[16] SMH, 4 Dec 1889, 7; Paul F Cooper. The Ministering Children’s League Philanthropy and Philanthropists in Australian Colonial History, 24 August 2023, available at colonialgivers.com/2023/08/24/the-ministering-children’s-league

[17] Paul F Cooper. William Ansdell Leech (1842-1895) and the Fresh Air League Philanthropy and Philanthropists in Australian Colonial History, 13/01/2024, available at colonialgivers.com/2024/01/13/ William-Ansdell-Leech-1842-1895-and-the-Fresh-Air-League

[18] Australian Town and Country Journal (Sydney, NSW), 24 May 1905, 43; 15 Nov 1905, 43.

[19] Punch (Melbourne, Vic.), 16 Nov 1905, 30.

[20] SMH, 5 Dec 1907, 4.

[21] Sydney Punch (NSW), 26 Jun 1880, 7.

[22] Sydney Punch (NSW), 26 Jun 1880, 7.

[23] Mrs Upper House Docker would have referred to Mrs Joseph Docker but it appears that it was Mrs Wilfred Docker who was actually part of the delegation. The Sydney Mail and New South Wales Advertiser (NSW), 1 May 1880, 843.

[24] SMH, 12 Jun 1888, 8.

[25] Evening News (Sydney, NSW), 3 Jul 1888, 5.

[26] SMH, Wed 15 Mar 1893, 4.

[27] Evening News (Sydney, NSW), 12 September 1895, 3.

[28] The Daily Telegraph (Sydney, NSW), 12 Sep 1895, 3.

[29] Freeman’s Journal (Sydney, NSW), 15 Oct 1887, 15; 17 Jun 1893, 18; 30 Jun 1894, 15; 15 Jun 1895, 9.

[30] Freeman’s Journal (Sydney, NSW), 23 Nov 1895, 15.

[31] Freeman’s Journal (Sydney, NSW), 23 Nov 1895, 15.

[32] Sydney Mail (NSW), 16 Apr 1913, 20.

[33] SMH, 30 Apr 1913, 7.