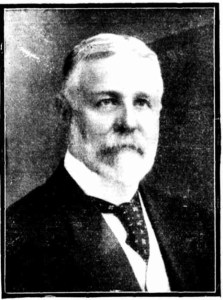

Upon the death of Wilfrid Law Docker (often misspelled as Wilfred) it was said that death had removed one of those men who are the salt of the community and furthermore that:

There are many whose loss would attract greater notice, but there are few who will be so long and so much missed in a number of public affairs touching the religious and philanthropic, and educational interests of this city.[1]

Who, then, was Wilfrid Law Docker? What had he done in his life to be accorded the designation of ‘salt of the community’? And why would he be ‘much missed in … the religious and philanthropic and educational interests’ of Sydney?

Docker was born on 2 May 1846 to English-born Joseph Docker (1802-1884) and Scottish-born Matilda Brougham, Joseph’s second wife. The birth took place at Scone, NSW, on the family property Thornthwaite, and he was given ‘Law’ for his second name, the family name of his great-grandmother, Agnes (1737-1819). Joseph was a surgeon who arrived in Sydney in 1834 and took up 10,000 acres which he named Thornthwaite after the area from which he came in England; he became a grazier and politician. On the death of his first wife Agnes nee Docker (?-1835), Joseph returned to Britain and in 1839 married Matilda Brougham, the daughter of Major James Brougham of the East India Company, and his wife Isabella nee Hay. The service was conducted by Rev John Sinclair one of the ministers of St Paul’s Episcopal Chapel, York Place, Edinburgh.[2]

Wilfrid, along with his brother Edward, received his schooling at the ‘Collegiate School’ at Cook’s River (CSCR), Sydney, which was run by the Rev William Henry Savigny, an Anglican, educated at the Bluecoat School, London, and was an Oxford graduate. Prior to coming to NSW in 1853, Savigny had taught at Bishop Corrie’s Grammar School at Madras and at the Sheffield Collegiate School.[3] He earned

… a reputation for severe discipline, even in those ‘hard’ days, and when administering corporal punishment to the batch of boys — a most unusual occurrence — it was his custom to punctuate his strokes with quotations from the classics in Latin.[4]

The school was not cheap at 60 guineas per annum, paid in advance, for each quarter year. The course of instruction embraced the ‘classics, mathematics, the French and German languages, ancient and modern history, geography, and elementary natural philosophy’.[5] It was also said of the school that ‘Banking establishments of the town, the offices of solicitors, and the counting houses of merchants will furthermore establish the truth that … [the] School has fulfilled its functions in giving to boys of the colony a sound, liberal, and commercial education’.[6]

As the CSCR was a boarding school that did not accept boys until they were 10 years old, Wilfrid would not have gone there until May 1856 at the earliest. It is probable that Wilfrid was taught by Savigny for the whole of his time at CSCR for Savigny remained at the school for six years until 1862 when he was appointed Warden of St Pauls.[7] Around this time, Wilfred would have left school to begin his commercial career.

Savigny was a keen promoter of cricket and matches were often played against other schools which may help explain why the Docker boys had, and retained for life, a great interest in cricket. Edward, his older brother by two years, also went to CSCR and played in the school team. He is mentioned in one of the few cricket scores published in the newspaper for a match in 1858 when, as a 14-year-old, he unfortunately got a duck in the first innings but improved to be 11 not out in the second innings. Mr Savigny’s school team, however, still lost.[8] Wilfrid would continue his love of cricket beyond school and played for the Sydney clubs ‘Toxeth’ in 1865 and ‘Warwick’ in the 2nds in 1866. He was awarded the club badge for the highest run average in the 2nd eleven – his average was 12 runs a game.[9]

In late 1866, Wilfrid joined the Albert Cricket Club as a player and by 1870 he was on the committee where he served until 1875 when he resigned to go overseas.[10] On his return from England in 1877, he re-joined the club and was also re-appointed to the Committee,[11] of which he became Secretary (1879-1882).[12] On his return to the club:

A letter was read from Mr W. L. Docker, who made the offer of a handsome and massive silver cup, which he had brought from England to be competed for during the ensuing two seasons and to be given to the player who during these seasons should obtain the highest aggregate number of runs. This valuable present, in the shape of a large goblet, formed of a mounted ostrich egg, supported by ostriches, was cordially acknowledged by a vote of thanks to the donor.[13]

As far as his cricket was concerned Docker could be a bit of a ‘batting bunny’ – lots of ducks recorded – but occasionally he did well once he put together a nice 30 consisting of 3 fours and the rest in singles.[14] He was more a bowler and it would appear quite a good one – in one match he took 6 for 32 and was always taking some wickets.[15] His last year of playing cricket was 1874 for a married man had more important things to do.

In February 1875, in a service at St Matthew’s, Botany, he married Ada Mary Lord (1851-1917) daughter of George W Lord (MLA) and granddaughter of the wealthy emancipated merchant Simeon Lord.[16] Wilfrid and Ada, soon after their wedding, left on the Nubia for their honeymoon, traveling to Venice and then to London.[17] They were to have no children.

Working Life

Upon leaving school, Wilfrid went to work for the Oriental Bank Corporation (OBC) in Sydney as a junior and made steady progress in his career with the bank.[18] OBC was an English bank that also operated in India, China, Singapore, Ceylon, Mauritius as well as Melbourne and Sydney.[19] In 1884, the OBC suspended payments due to significant financial losses.

For a length of time, it has been known that the bank has not been in a very flourishing condition. Heavy losses were encountered in connection with large sugar plantations held by the bank in Mauritius … and in other parts of the world. The business of the bank in the colonies has been of a satisfactory and remunerative character and the stoppage is in no way attributable to the Australian transactions.[20]

The Bank’s failure had little impact in the NSW Colony, but it was the bank used by the NSW Government and from this point on the Bank of NSW became the government’s favoured bank. In April 1882, before the Bank was suspended, the Dockers left Sydney and traveled to San Francisco on the ‘RMS Australia’ and then on to London, presumably by the transcontinental railway.[21] They arrived back in Sydney on the ‘RMS Rome’ arriving in April 1884, just as the news broke about the closure of the OBC.[22]

Wilfrid joined the reconstructed New Oriental Bank Corporation and in 1889 was its accountant, The following year he was the acting manager until he was appointed liquidator of the company’s assets when, in 1892, it finally went out of business.[23] In 1893, he started business as the firm of Wilfrid L Docker, public accountant, and auditor, later becoming Wilfrid L Docker and Docker, upon taking into partnership his nephew, Keith Docker.[24] He secured a large clientele and became an auditor for many of the large companies of Sydney, such as the Commercial Bank (1900-1918)[25] and the Australian Gaslight Company (1901-1913)[26] as well as for organizations such as St. John’s Ambulance.[27] He also did a large number of honorary auditing tasks for organizations such as the District Nurses Association (1905- 1918); the Girls’ Friendly Society; and the Civil Ambulance and Transport Corps of the St. John Ambulance Brigade.[28] Wilfrid was Chairman of the board of New Redhead Coal Mining Company from 1894 until his death in 1919. The company did not mine coal, but they received payments for the use of a railway in the Newcastle Coal field which had been purchased from the liquidators of the Redhead Coal Mining Company in 1894 of which Wilfrid had been one of the liquidators.[29]

He chaired the inaugural meeting of the Corporation of Accountants, held in April 1900 in Sydney, and in his opening address he indicated some of the principal objects for which the corporation had been formed, and which it hoped to accomplish. These were:

1. To provide a special organization for accountants and auditors, and to do all such things as from time to time may be necessary to elevate the status and advance the interests of the profession. 2. To provide for the better definition and protection of the profession through the supply of thoroughly educated professional men through a system of examinations and the issue of certificates and the conferring of titles and degrees of classification. 3. To promote and foster in commercial circles a higher sense of the importance of systematic and correct accounts and to encourage a greater degree of efficiency in those engaged in bookkeeping. 4. To provide opportunities for intercourse amongst the members and associates, and to give facilities for the reading of papers and the delivery of lectures and for the acquisition and dissemination by other means of useful information connected with the profession, and to encourage improved methods of bookkeeping.

And Wilfrid believed that

… one of the most fruitful causes of bankruptcy was the inefficient method of keeping books, or no books at all. If this fact could be impressed upon the business portion of the community and they were induced to insist upon a proper system of bookkeeping merchants and bankers would be the gainers to a very large extent, and the public would be better protected by a proper system of audit by skilled auditors.[30]

Initially, he was only a member of the committee of the Corporation of Accountants but was appointed President in 1901 and served as such until 1909.[31] Upon the formation of an Australia-wide accountant organization in 1908/9, he was appointed to the committee of the NSW register of the newly formed Australasian Corporation of Public Accountants and served from 1910 to 1912.[32]

Church Involvement

Docker was described as a ‘Thorough Anglican’,[33] an association that was begun when he was baptized at St Luke’s, Scone:

For many years Mr Docker did some Church work every day, and on most days it ran into hours. As churchwarden of St. John’s Church, in the Darlinghurst road, he attended personally to many local matters. In fact, as far back as Bishop Pain’s time, he was an almost daily visitor to the rectory. As hon. secretary for the old Church Society he also did daily work, spending a great many of his early morning hours attending to its financial matters.[34]

Docker was a Church Warden at St John’s Darlinghurst Road, Darlinghurst, for 30 years being first appointed in 1888.[35] This role was one of some importance and would have required a significant commitment of time and effort.

Docker was deeply involved in the financial affairs not just of his local church but also of the Diocese of Sydney. He became lay-secretary and treasurer of the Church Society (CS) in 1894 and continued in that role until 1918[36] (in 1911 it became known as the Home Mission Society),[37] and the Mission Zone Fund which commenced in 1904 under the CS and was for evangelizing those unreached by the church within the Diocese.[38] Thus, Docker became involved during a difficult financial period for the church as the 1890s depression was no doubt reducing the income the church received from its parishes and parish auxiliaries. According to Anderson, also added to this difficulty for the CS was the weak leadership of the evangelical Archbishop, Saumarez Smith, in the face of competing claims on the funds that were raised.[39] At some point, Docker became a Trustee of the Anglican Endowment Fund.[40]

While he also had an interest in temperance issues, it was not through the wider temperance non-denominational movement but through that involving the Church of England. He became a founding member of the Church of England Temperance Society (CETS), its treasurer, and also the treasurer of the Society’s Church Home. Opened in 1884, the Church Home was established in Forbes Street ‘for the reception of the fallen and intemperate, without any respect of creed.’[41] Wilfrid encouraged people to support the work ‘from a sense of duty as Christians, as members of the Church of England and for its own sake’.[42] The premises soon became too small and in 1886, through the exertions of Wilfrid, which cost him ‘much time and trouble’, larger premises were procured for the Church Home at the corner of Crown and Albion Streets.[43] When the lease on these premises was due to expire Docker then found another suitable property in Waverly that could be purchased for use as the Church Home.[44]

CETS seems to have had a preference for a total abstinence policy. When the committee had under consideration a proposal to hold a congress of the temperance bodies, in connection with the approaching celebration of the centenary of the colony, it was ‘agreed that all writers of papers and selected speakers upon subjects other than political should be total abstainers’.[45] It appears that Docker did not agree with this position for, at the same meeting when the above decision was made, he presented a paper on the recent formation and operation of the CETS in England. He stressed that

… the basis of the society was the union and co-operation on perfectly equal terms between those who use intoxicating beverages and those who abstain from their use, the one common object of the members being to cope with and subdue the evil of intemperance.[46]

He was still actively involved in 1907 as vice president of the Church Home and CETS, and as Chairman of the 1907 Annual Conference of CETS.[47]

For many years, Docker was a member of the Chapter of St Andrew’s Cathedral, a member of the standing committee of the Diocesan Synod, the Synod of the Province and the General Synod of Australia. He served as honourary treasurer of the Clergy Provident Fund, and it was due largely to his efforts that, by 1919, the fund was one of the strongest of its kind in the whole Anglican community.[48]

Wilfrid was a member of the council and honorary treasurer of the Church of England Grammar School for Girls (SCEGGS) from March 1897 until his death in 1919.[49] The school had opened in July 1895 in Victoria Street North with Miss Badham and two assistants and five pupils. An ordinance to regulate the school was passed by the Synod in October 1895.[50] The school soon moved to ‘Chatsworth’, Potts Point, and then, in 1900, moved to ‘Barham’ which was a two-acre site in Darlinghurst.[51] The finding, financing, and purchasing of this permanent home for the school was largely due to Wilfrid.[52] ‘As time progressed … Docker showed himself to be invaluable to the Council because of his financial acumen and sound, reliable advice’.[53]

Over the long period of his membership on the Council of SCEGGS, Wilfrid did not restrict his interest in the school to attendance at Council meetings and financial matters. Along with Mrs Docker, they often involved themselves in the life of the school: presenting prizes, attending dances and school concerts, plays, and fundraising or traveling to Bowral to ‘Woodbine’, an offshoot of the Sydney school, to represent the Council.[54]

While there was perhaps little public recognition during his lifetime of Wilfrid’s service to the school, at his funeral his value to the school, and the regard in which he was held, was seen by the presence of ‘a number of pupils from the Church of England Grammar School for Girls, Darlinghurst, under Miss Badham,’ in the congregation.’[55] Miss Badham clearly highly valued Wilfrid’s contribution and wished to acknowledge his work in a tangible way. In 1926, when the Archbishop of Sydney dedicated the chapel in the name of the late Miss Edith Badham, the first principal of the school, it was noted that:

It had been Miss Badham’s wish for many years that the old assembly hall should be converted Into a chapel and dedicated to the late Mr. Wilfred Docker, the first honorary treasurer of the school council, but when she died in 1920 the members of the Old Girls’ Union decided that it should be called after their late principal.[56]

In 1926, under the leadership of SCEGGS’ second headmistress, Miss Dorothy Wilkinson, the common practice by schools of naming houses (groups of students) after prominent people who have contributed significantly to a school was adopted at SCEGGS. One house was named ‘Docker’ which, it would appear, was an alternative act of recognition to the one envisaged by Miss Badham.

Wilfrid’s memory was also celebrated when a bronze tablet was erected by the churchmen of the Diocese in the chapter house in honour of him. It was unveiled by Archibishop Wright as a tribute to a man who was, in the Archbishop’s words, ‘an eminent churchman’.[57] A memorial was also erected at St John’s Darlinghurst in his memory.[58]

Other Organisations

Wilfrid first became involved with coursing (greyhound racing) in February 1881 when he was elected a member of the NSW Coursing Club and by October 1881, he had joined the governing committee though his stay was short. He resigned in May 1882, but served again as a committee member in 1886.[59] In this interest, he was particularly associated with his brother-in-law, H E Lord, and with his mother-in-law’s family, the Lees, who were important figures in the Sydney coursing community. Lord had his own stud kennels at Botany and gave Wilfrid charge of his coursing interests when he departed, in October 1884, for an eighteen-month visit to ‘the old country’. By June 1885, however, he had given Wilfrid instructions to arrange for the sale of the kennels and his prized racing dogs.[60] Beyond 1886, it would appear that Wilfrid was no longer actively involved in the sport.

From 1888 to at least 1903, Wilfrid was a member of the Home Visiting and Relief Society and, during the economic downturn of the 1890s, he took a leading role in chairing its meetings.[61] The Home Visiting Relief Society was an organization that gave financial assistance to the ‘educated classes’ who were generally reticent to ask for assistance.[62]

Wilfrid joined the Committee of the St. John’s Ambulance Association in 1892, became its auditor in 1895, and, though not the usual practice of an auditor, continued to also attend meetings of the committee until 1902.[63] In 1904, the committee was pleased to announce the amalgamation of the Civil Ambulance and Transport Brigade with the St John Ambulance Association. From this time onwards, Wilfrid no longer attended meetings of the committee, but he continued as the auditor at least until 1916.[64]

With the coming of Word War 1, Wilfrid and Ada took up duties and causes that related to the war effort. Wilfrid was President of the Australian League of Girl Aids whose objects were: to train girls in first aid, flag signaling, camp cooking with improvised equipment, land drill in connection with life-saving in the water, and also to be of service to their county should their services be needed at any time.[65]

In 1914 until 1918, Wilfrid was the Red Cross Honorary Treasurer and he was praised by the Government Auditor for his work as Treasurer.[66] He was interviewed in his capacity as Treasurer during WWI and was asked the question, how might those who could not, or who were not fit enough to enlist, serve their country? His answer was practical:

You know we have a book depot in Pitt-street, near Moore-street, which receives and distributes large quantities of books for the use of the hospitals and hospital ships at home and abroad. These books and periodicals have all got to be sorted, packed, and nailed up in cases, and we should be very glad of assistance in this work.[67]

Wilfrid took up golf and became a member of the Australian Golf Club. In 1901, he won a B Grade competition at the Australian Golf Club playing off a handicap of 28 and scoring 118 with a net score of 90; by 1909, he was playing off 12.[68] In 1903, he presented the Docker Trophy to the club as a prize to be awarded in an annual golf competition[69] and in 1906, he became Treasurer serving until 1914[70] after which, in 1915, he became a vice president of the club.[71]

Mrs W L Docker

Mrs W L Docker, or more fully Ada Mary Docker nee Lord, was the great-granddaughter of the wealthy emancipated merchant Simeon Lord (1771–1840).[72] The life she lived was determined by her circumstances: she and Wilfrid were childless; they were socially well connected and well off; and they lived in Darlinghurst among those of a similar social status. Her name appeared very frequently in the social pages of the newspaper, so much so that she and her friends were dubbed by one writer as ‘Mrs Wilfred Docker, and many other fashionables’.[73] On such social occasions, and having no daughter, she was often accompanied by her niece, Miss Madeline Docker.

The Dockers mixed with the Governor, the titled, the wealthy, the high-ranking clergy – in short, the social elite of Sydney society. Visiting Bishops and Archbishops would stay at their house and she attended a constant stream of social events: ‘at homes’; occasions at the Governors; at Balls; and various other social events, sometimes with Wilfrid. Her dress was frequently reported upon, presumably for the benefit of lady readers, such that she must have had an extensive wardrobe.

She was frequently involved in organising social events for the benefit of various charities and causes, mixing with similarly socially positioned women who gave of their time for these causes. Her most notable efforts were connected with World War I.

Mrs Wilfred Docker, a daughter of the old-time family the Lords and wife of a prominent war-worker from the very beginning. There are names which one instinctively associates with Sydney women’s war efforts; such as Langer- Owen, both mother and daughter, Kettlewell, Corbett, Greatorex, their names crop up day after day, the herculean stayers no matter what there is to be done, and Mrs. Wilfred Docker was just one of these, indefatigable, retiring and untiring, and the Red Crossites have lost a devoted friend and an earnest worker.[74]

Ada did not just concern herself with the returned wounded soldiers through the Red Cross but, when asked as a leader in women’s society, she spoke forthrightly about the need for mothers to encourage their sons to volunteer. While not doubting her sincerity, the fact that she had no children and was advocating sacrifices that she did not have to make, it seemed not to occur to Ada that this was a view better left for others to express. She had said:

‘Duty’ should be the watchword of Australia to-day. Long have we worshipped at the shrine of pleasure. Now we are called upon to enter deeply into the serious side of life, and we must not be content with half-way measures. The salvation of our country, freedom, and every principle we hold dear, now depends upon our young men. It is their duty and privilege to come forward and support the men who have already shouldered the burden, and are now doing battle for them or preparing to do their part. Mothers should help their boys in this matter. It may be difficult, but better far to help them in their desire to go than have them reproach us afterwards, or awaken the feelings of responsibility and duty, rather than have the powers-that-be force them into doing their duty. I feel strongly that a large meeting of the young men between the ages of twenty and twenty-five should be called and addressed by our prominent speakers, who would put the position so forcibly before them that their conscience would be so awakened that no power on earth could prevent them offering to do their part.[75]

She was Treasurer of the Ashfield Infants Home (1880-1893);[76] on the Ladies Committee of Women’s College (1890-1);[77] a member of the Ladies Committee Sydney City Mission (1893-1896);[78] President of Girl’s Friendly Society (1895);[79] Vice President of St John’s Darlinghurst branch of the Ministering Children’s League (1899)[80] and in that capacity she explained that:

The idea of the League was to spread the knowledge, particularly among young people, of the value of doing something always for somebody else. Much indeed could be done by children, by each becoming a ‘sunbeam’ – bring sweetness and unselfishness into the home. Let each one remember the valuable motto of the Society – ‘No day without a deed to crown it.’[81]

From 1905 until 1907, Mrs Docker was a vice president of the women’s committee for the British Empire League along with Lady Barton and Lady Harris.[82] The British Empire League had as its aim the maintenance of links with the ‘old country’ and Mrs Docker was keen to do this; she was a pioneer of the women’s branch in Sydney.[83] At a farewell to her on the occasion of one of her trips to England, it was recorded that:

The vice-president of the women’s branch of the British Empire League (Mrs Wilfred Docker) left for England last Saturday by the R.M.S. Britannia. A number of the league members went on board to say ‘au revoir’ to Mrs Docker, and to wish her a pleasant journey and a safe return. Mrs Docker has always done much for the league, and some of her papers which she read during the various meetings were most interesting— more especially those dealing with life in India.[84]

What is not mentioned in this account is that, as a farewell gift, the women gave Mrs Docker a bunch of roses and a ‘Union Jack’ silk cushion.

Travel

Mr and Mrs Docker, and Mrs Docker in particular, made numerous sea voyages which meant that, in Mrs Docker’s case, she was away from Sydney for many months at a time. Those trips were 1875-1877, a honeymoon to Venice then to London (24 months); 1882-1884, to London (24 months); 1892, to Hong Kong (3 months); 1895, to London (9 months); 1902, to India (6 months); 1907, to London, Scotland and Germany (14 months); 1912, to London (9 months); and in 1915, to Hobart (1 month).[85] The frequency of the travel and its duration could only have been sustained by having significant financial resources which the Dockers clearly possessed.

On her death in 1917, His Grace the Archbishop of Sydney said that her ‘life had ever been a pattern of noble womanhood’ and the Sunday Times newspaper commented that by her death ‘the Church of England loses a zealous worker, who will be greatly missed.’[86]

Two years later, when the influenza epidemic arrived in Sydney in 1919, Wilfrid became ill and died shortly afterward.[87] An obituary in the Melbourne Argus succinctly summarised his life in this way:

The death of Mr. Wilfred Docker removes one of those men who are the salt of the community. Never conspicuous, never in public life, he gave abundantly of his services, his time, and his means in all movements for the public good. He was a religious man, and while closely identified all his life with the efforts of the Anglican Church, he refused to nobody of earnest men and women whatever help and counsel he could give in promoting public objects. There are many whose loss would attract greater notice, but there are few who will be so long and so much missed in a number of public affairs touching the religious and philanthropic and educational interests of this city.[88]

There is little doubt that in Wilfrid’s life of service the appellation ‘salt of the earth’ was not an exaggeration and that upon his death his willing and voluntary service was indeed missed in philanthropic and educational circles. Fortunately for such circles, however, Wilfrid was just one of the many philanthropically minded men and women who, both before and after him, willingly and voluntarily gave of their service to the benefit of colonial and post-colonial NSW.

Paul F Cooper

Research Fellow

Christ College, Sydney

The appropriate way to cite this article is as follows:

Paul F Cooper. Wilfrid Law Docker (1846-1919) Accountant and a thorough Anglican Philanthropy and Philanthropists in Australian Colonial History, 10 August 2023, available at colonialgivers.com/2023/08/10/wilfrid-law-docker-1846-1919-accountant-and-a-thorough-anglican/

[1] The Argus (Melbourne, Vic), 15 July 1919, 4.

[2] Wedding of Joseph Docker and Matilda Brougham, 22 April 1839, Scotland’s People.

[3] Launceston Examiner (Tas), 6 Aug 1889, 2; SMH, 18 Nov 1861, 1; 27 Oct 1853, 5; Empire (Sydney, NSW), 26 Oct 1853, 2 ;https://monumentaustralia.org.au/themes/people/education/display/109396-william-savigny [accessed 10/8/2023}.

[4] National Advocate (Bathurst, NSW), 26 Jun 1948, 3.

[5] SMH, 18 Jun 1855, 1.

[6] Launceston Examiner (Tas), 20 Aug 1885, 3.

[7] Launceston Examiner (Tas), 20 Aug 1885, 3; SMH, Fri 7 Mar 1862, 5.

[8] Empire (Sydney, NSW), 18 Mar 1858, 4.

[9] SMH, 6 Mar 1865, 5; 20 Sep 1866, 5; Sydney Mail, 9 Feb 1867, 2.

[10] Sydney Mail 10 Nov 1866, 7; 23 Feb 1867, 3; Australian Town and Country Journal (Sydney, NSW), 28 Aug 1875, 30; Bell’s Life in Sydney and Sporting Chronicle, 30 Apr 1870, 4.

[11] The Sydney Mail and New South Wales Advertiser, 22 Sep 1877, 374; 28 Sep 1878, 500.

[12] The Sydney Mail and New South Wales Advertiser, 27 Sep 1879, 506; The Sydney Daily Telegraph, 16 Sep 1880, 4; 17 Sep 1881, 6; SMH, 11 Sep 1882, 8.

[13]The Sydney Mail and New South Wales Advertiser, 22 Sep 1877, 374.

[14] The Sydney Mail and New South Wales Advertiser, 28 Mar 1874, 406.

[15] SMH, 26 Oct 1869, 3.

[16] SMH, 4 Feb 1875, 1; they left Sydney on 20/2/1875. SMH, 22 Feb. 1875, 37.

[17] They boarded the Ellora for Melbourne and there the Nubia for Venice. The Maitland Mercury and Hunter River General Advertiser, 23 Feb 1875, 4; SMH, 2 2 Feb 1875, 4.

[18] Evening News (Sydney, NSW), 5 Mar 1873, 3. He eventually became a teller.

[19] SMH, 9 May 1884, 6.

[20] The Herald (Melbourne, Vic), 3 May 1884, 3.

[21] The Sydney Mail and New South Wales Advertiser, 22 Apr 1882, 637.

[22] SMH, 25 Apr 1884, 6.

[23] New South Wales Government Gazette (Sydney, NSW), 9 Jul 1889 [Issue No.353], 4712; 17 Oct 1890 [Issue No.593] 8045; SMH, 24 Sep 1892, 3; as liquidator the task was completed by him in 1897; SMH, 16 Jun 1897, 4.

[24] SMH, 14 July 1919, 9.

[25] The Daily Telegraph (Sydney, NSW), 21 Jul 1900, 13; The Sun (Sydney, NSW), 26 Jul 1918, 6.

[26] The Daily Telegraph (Sydney, NSW), 29 Jul 1902, 3; The Sun (Sydney, NSW), 28 July 1913, 7.

[27] The Daily Telegraph (Sydney, NSW), 19 Oct 1905, 3; SMH, 22 Oct 1918, 8; Evening News (Sydney, NSW), 7 Sep 1895, 4.

[28] SMH, 24 Dec 1895, 3; 29 Nov 1907, 5; Punch (Melbourne, Vic.), 29 Oct 1914, 34.

[29] ‘The New Redhead Coal Company’s railway. The lines owned by this company branch from the Northern line of the Government railways, and run from Adamstown to Burwood Extended Colliery, and from Adamstown to Dudley Colliery, a total distance of 8 miles. The lines are worked by the Railway Department, coal waggons being supplied in part by the coal companies using the line. The colliery companies using the line pay a way-leave for right to run their coal over the line and the Railway Commissioners allow the New Redhead Company a proportion of the revenue from the passenger and goods traffic.’ Australian Town and Country Journal (Sydney, NSW), 14 Apr 1915, 42.

[30] SMH, 26 Apr 1900, 4.

[31]SMH, 30 Mar 1901, 7; 16 May 1906, 8; The Daily Telegraph (Sydney, NSW), 31 Jan 1908, 11; Evening News (Sydney, NSW), 23 March 1909, 7.

[32] SMH, 20 Aug 1910, 6; The Richmond River Express and Casino Kyogle Advertiser (NSW), 3 Mar 1911, 2; SMH, 2 Feb 1912, 8.

[33] Evening News (Sydney, NSW), 14 July 1919, 4.

[34] Evening News (Sydney, NSW), 14 July 1919, 4.

[35] SMH, 16 Feb 1889, 3; 25 Apr 1889 9; 10 Apr 1890 4; 16 Apr 1892, 11; 1 Apr 1893, 14; 7 October 1893, 5; The Australian Star (Sydney, NSW),14 April 1896, 3; The Daily Telegraph (Sydney, NSW), 20 Apr 1898, 10; Evening News (Sydney, NSW), 20 May 1902, 8; The Australian Star (Sydney, NSW), 30 Apr 1904, 5; SMH, 21 Jul 1919, 12.

[36] The Australian Star (Sydney, NSW), 6 Apr 1894, 2; The Daily Telegraph (Sydney, NSW), 7 Dec 1900, 1; South Coast Times and Wollongong Argus (NSW), 13 Aug 1904, 11; The Daily Telegraph (Sydney, NSW), 12 Jun 1909, 6; SMH, 13 Sep 1910, 9.

[37] SMH, 29 Sep 1911, 5.

[38] SMH, 7 Oct 1904, 6; Sunday Times (Sydney, NSW), 2 Jun 1918, 11;

[39] Anderson, Donald George, The bishop’s society, 1856 to 1958: a history of the Sydney Anglican Home Mission Society, Doctor of Philosophy thesis, Department of History and Politics, University of Wollongong, 1990. http://ro.uow.edu.au/theses/1440

[40] The Daily Telegraph (Sydney, NSW), 25 May 1912, 10.

[41] SMH, 13 Sep 1884, 11; The Daily Telegraph (Sydney, NSW), Jul 1885, 6; 23 Jan 1886 5; SMH, 1 May 1886, 3.

[42] Daily Telegraph (Sydney, NSW), 20 June 1888, 6.

[43] The Daily Telegraph (Sydney, NSW), 23 Jan 1886, 5.

[44] SMH, 17 Jan 1890, 3.

[45] SMH, 15 Jun 1887, 7.

[46] SMH, 15 Jun 1887, 7.

[47] Evening News (Sydney, NSW), 30 May 1894, 3; SMH, 15 May 1907, 10.

[48] Evening News (Sydney, NSW), 14 July 1919, 4.

[49] See Marcia Cameron, SCEGGS A Centenary History of the Church of England Girls’ Grammar School (St Leonards, NSW: Allen & Unwin, 1994), for a history of the school.

[50] Australian Town and Country Journal (Sydney, NSW), 12 Oct 1895, 8; SMH, 22 Sep 1899, 8; Sydney Mail, 30 Jul 1919, 25.

[51] SMH, 23 Jun 1900, 7.

[52] SMH, 23 Jun 1900, 7; 5 Oct 1900, 8. Cameron, SCEGGS, 34.

[53] Cameron, SCEGGS, 31.

[54] Lux: magazine of the Sydney Church of England Girls’ Grammar School, Darlinghurst, June 1904, 12; Jan 1914, 8, Sept 1906,1; The Daily Telegraph (Sydney, NSW),11 Dec 1908, 4; The Wollondilly Press (NSW) 30 Jan 1907, 2.

[55] SMH, 15 Jul 1919, 9.

[56] SMH, 18 Dec 1919, 9; The Daily Telegraph (Sydney, NSW), 10 Apr 1926, 2.

[57] SMH, 24 Nov 1921, 6.

[58] Sunday Times (Sydney, NSW), 11 Apr 1920, 5.

[59] Australian Town and Country Journal (Sydney, NSW), 20 May 1882, 34.

[60] The Sydney Mail and New South Wales Advertiser, 4 Oct 1884, 691.

[61] SMH, 13 Aug 1894, 1; 10 Mar 1897, 8: 12 Feb 1903, 6.

[62] Paul F Cooper. Home Visiting and Relief Society, Philanthropy and Philanthropists in Australian Colonial History, December 19, 2017. Available at https://phinaucohi.wordpress.com/2017/12/19/home-visiting-and-relief-society

[63] The Australian Star (Sydney, NSW), 8 Feb 1892, 3; Evening News (Sydney, NSW), 7 Sep 1895, 4; Evening News (Sydney, NSW), 8 Feb 1896, 5; SMH, 10 May 1897, 3; 29 Sep 1899, 6; 2 Mar 1900, 8; 14 Jan 1901, 9; 13 Jan 1902, 10;

[64] SMH, 23 Sep 1904, 6; 1 Oct 1909, 3; 30 Nov 1916, 8

[65] The Sun (Sydney, NSW), 10 May 1914, 19.

[66] SMH, 10 Sep 1914, 6; The Daily Telegraph (Sydney, NSW), 22 Jan 1915, 3; SMH, 29 Aug 1918, 7.

[67] Sunday Times (Sydney, NSW), 17 Oct 1915, 8.

[68] The Daily Telegraph (Sydney, NSW), 26 Aug 1901, 8; 2 Jun 1909, 10.

[69] SMH, 22 Jun 1903, 4.

[70] Australian Town and Country Journal (Sydney, NSW), 4 April 1906, 52; Evening News (Sydney, NSW), 26 Mar 1907, 2; The Sydney Mail and New South Wales Advertiser, 25 March 1908, 826; 3 May 1911, 55; SMH, 29 April 1914, 8.

[71] Referee (Sydney, NSW), 5 May 1915, 7; SMH, 17 Apr 1919, 9.

[72] D. R. Hainsworth, ‘Lord, Simeon (1771–1840)’, Australian Dictionary of Biography, National Centre of Biography, Australian National University, https://adb.anu.edu.au/biography/lord-simeon-2371/text3115, published first in hardcopy 1967, accessed online 27 March 2023.

[73] National Advocate (Bathurst, NSW), 26 Dec 1893, 1.

[74] The Maitland Daily Mercury (NSW), 7 Apr 1917, 9.

[75] Sunday Times (Sydney, NSW), 6 Jun 1915, 8.

[76] SMH, 29 May 1880, 15; Illustrated Sydney News (NSW), 22 Apr 1893, 7. Probably not continuous service due to overseas travel.

[77] SMH, 9 Sept 1890, 6; 6 Apr 1891, 9.

[78] Daily Telegraph (Sydney, NSW), 6 Jun 1893, 3; Evening News (Sydney, NSW), 22 May 1896, 6.

[79] SMH, 24 Dec 1895, 3.

[80] SMH, 27 Nov 1899, 3.

[81] Cumberland Argus and Fruitgrowers Advocate (Parramatta, NSW), 28 November, 1900,1..

[82] Evening News (Sydney, NSW), 26 May 1906, 4; The Daily Telegraph (Sydney, NSW), 1 July 1907, 5.

[83] The Sydney Mail and New South Wales Advertiser, 16 Aug 1905, 441.

[84] The Sydney Mail and New South Wales Advertiser, 20 Feb 1907, 491.

[85] SMH, 22 Feb 1875, 4; The Sydney Mail and New South Wales Advertiser, 30 Nov 1878, 862; 22 Apr 1882, 637; Sydney Daily Telegraph, 20 Apr 1882 2; SMH, 25 Apr 1888,9; The Sydney Mail and New South Wales Advertiser, 26 Apr 1884, 805; SMH, 15 Ap 1892, 5; The Australian Star (Sydney, NSW),16 Apr 1892 4; 26 Jul 1892 , 4; Sydney Daily Telegraph, 22 Mar 1895, 7; 21 Dec 1895, 13; Australian Star, 3 Oct, 1902, 3; Sydney Daily Telegraph, 4 Apr 1903, 4; 3 Apr 1903, 7;15 Feb, 1907, 4; SMH, 4 December 1907,5; 14 Feb 1912, 20; Evening News, 15 November 1912; Sydney Daily Telegraph, 12 May 1915,6.

[86] Sunday Times (Sydney, NSW), 1 Apr 1917, 11.

[87] Northern Star (Lismore, NSW), 14 Jul 1919, 4.

[88] The Argus (Melbourne, Vic), 15 July 1919, 4.

[…] including leading NSW female philanthropists such as Lady Darley, Mrs Wilhelmina Stanger-Leaves, Mrs Ada Docker and Mrs Ann Goodlet. Its success, however, was due to the efforts of the many parents, particularly […]

LikeLike