The Sydney General Poor Relief Fund (SGPRF) was so named to indicate its purpose. In the period just prior to World War I, it was promoted so that the poor of Sydney might enjoy the sympathy and some financial support of those who were better off. It was, however, a fake charity enriching and providing not for the poor but for an unscrupulous ‘con man’. Not all involved with charity were dishonest. Some who worked as fundraisers for the so-called charity were as duped as the general public.

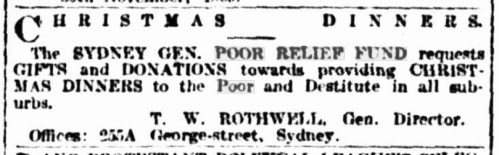

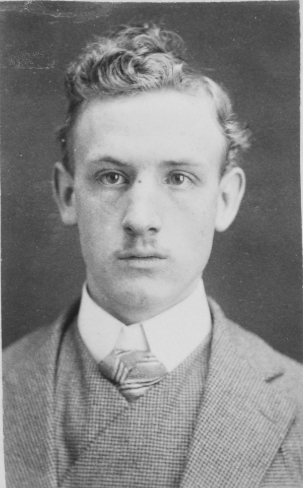

The Fund was first mentioned in the Sydney Morning Herald 22 November 1909 when a notice, designed to tug on the heartstrings of the sympathetic, was published. It sought gifts and donations towards providing Christmas dinners to the poor and destitute:[1]

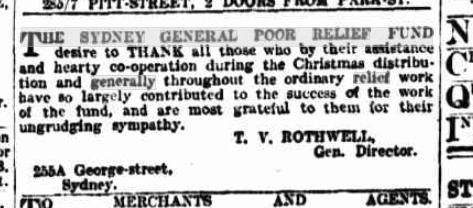

And this was followed with an after-Christmas thank-you note for the support the Fund had received, and it hinted about the support it had received for its more general relief program:[2]

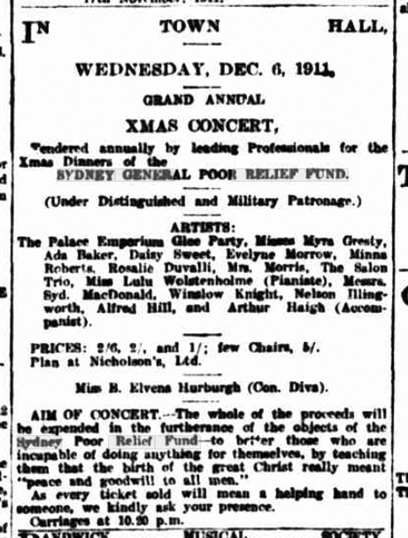

Around this time, other concerts were organized by musicians who gave of their time and talents, and the money raised through ticket sales was given to the SGPRF. One such concert was held in the Balmain Town Hall in 1909 under the patronage of the Mayor and Mayoress of Balmain and was organized by Miss B Elvena Hurburgh, a piano teacher,[3] who went on to organize further fundraising concerts for the SGPRF. With increasing attendance, her concert was moved to the Sydney Town Hall with musicians giving of their services for the event. It was so well supported, by both musicians and the public, that it became an ‘annual’ event, providing further funds for the SGPRF up until 1914.[4] Other musicians organized their own concerts for the SGPRF like the piano concert given by Aaron Solomons, with assistance from other musicians, in the YMCA in 1909.[5] Another successful event was the harbour excursion and concert organized by Mrs Haffenden-Smith, assisted by her pupils, which was held aboard the Lady Northcote in 1910.[6]

Elvena Hurburgh, in aid of the SGPRF, joined a touring company which gave performances in January 1912 on the South Coast[7] and, shortly after her marriage to the honorary director of the SGPRF, she even participated in a musical performance in Berrigan.[8] There was clearly strong support for the SGPRF within the Sydney music community. It was no doubt seen by such as a good opportunity to preform before an audience and a good time to include their students so that they might gain valuable stage time experience.

In November and December 1909, the first advertisements for SGPRF appeared under Rothwell’s name:

THE SYDNEY GENERAL POOR RELIEF FUND desire to THANK all those who by their assistance and hearty co-operation during the Christmas distribution and generally throughout the ordinary relief work, have so largely contributed to the success of the work of the fund, and are most grateful to them for their ungrudging sympathy. L. V. ROTHWELL, Gen. Director. 255A George-street, Sydney[9]

In about February 1909, Rothwell also sought to expand the reach of the fund and increase its income and Mr ET Perry was employed as the official collector for the Fund. Initially, for his first ten months, Perry canvased the Sydney area for donations, but this appears to have proved to be stony ground and the work was ‘thankless, discouraging and monotonous’. He turned his attention to the country areas where the results were much better and his visits were ‘always … encouraging and successful’.[10]

At the end of his time as a collector in 1914, Perry, in an unusual step for a collector, wrote an account of his time canvassing for the SGPRF. He wrote of the areas he visited and gave his observations of the response of the people to charity collectors:[11]

I must say that a very good percentage of the country people in all the country districts I have visited, especially those of the working class and of the poor, are the most sympathetic. A good percentage of the middle class are also sympathetic, though some are very good at making excuses and crying “the poor mouth,” and it is not an uncommon occurrence for me to discover afterwards that they are well off. As far as my personal experience goes, I have found the wealthy the worst to deal with, particularly in Sydney, though I would not make the sweeping assertion I have often heard that the rich never give or will not give at all; but, I’ll be bold enough to say that as far as I can see, and as far as I know from experience, at least 80 per cent. of the wealthy do not give according to their means (whereas the working class, and the poor often do) to help their unfortunate brethren, I have met with some who have made me think that I could talk for an hour, and nothing would induce them to give, though they are very few in number. Most people are sympathetic with the work, even if they cannot proffer a donation. It frequently happens that people have “not got any change in the house,” but when I can see that they mean what they say when they remark that they would give “if they had it” I usually bid them adieu with the remark, “Alright, I’ll take the will for the deed, that’s as good as a donation!“[12]

Perry who seems to have been a well-educated and diligent man, and who claimed some Scottish heritage, seems to have been genuine in his efforts on behalf of Sydney’s poor. He wrote:

… my experiences have been chiefly pleasant and varied, but it would take too long to relate them all in detail. The work requires persistency and determination, and as I claim to have some Scotch in me, it is just as well. But in addition to the arduous work of collecting, I have advertised the Sydney Poor Relief Fund considerably and tried to procure men work in the country. During the three years of the work, I calculate that I have visited about 60,000 homes in Sydney, included some scattered in the country, and 80 different country towns and townships and walked (apart from cycling) about 6,000 miles. I trust the readers of this short account of philanthropic work will not consider me an egotist, for I am fully aware of the veracity of the maxim, ”Self-praise is no recommendation”. However, I feel fully justified in concluding by saying that I have done my share for the relief of the poor, and likewise endeavoured to bring about the amelioration of the conditions of suffering humanity and of the deserving poor. The worker for the poor should go forth in an optimistic spirit and “with a heart for any fate,”[13] and his motto should be, “Nil Desperandum”.[14]

He did not, in his account, indicate how much money had been collected for the charity by his efforts. Later, however, it was revealed that during his 3 years of visiting, he had collected some £600, with the collector retaining £400 for salary and expenses, and the remaining £200 was passed on to Rothwell for the use of the charity.[15] Little was known about the internal organization of this charity, apart from its appeals for support and its notices of fundraising concerts. Nevertheless, the involvement of prominent community figures lent a note of authenticity to the activities of the SGPRF. It did not hold widely advertised public meetings, nor were the financial figures of its balance sheet widely circulated. It seems that in a spirit of goodwill towards the ‘deserving poor’, it was assumed by the public and community figures that the Fund was what it purported to be – a Fund to help the poor.

In 1909, however, a balance sheet was issued for the last quarter of 1908, October 1 to December 31, detailing income and expenses; it also contained the names of committee members. An analysis of the information provided was done by a local Wagga Wagga newspaper (The Worker) and it came to the conclusion, that

… a fund which professes to be collected ‘for God and man’— that is, for charitable purposes — and that, with the exception of an insignificant fraction, is diverted to quite extraneous uses, seems nothing short of a sham and a humbug. Its promoters’ use of the name of the Deity seems, on their own figures, a piece of bold blasphemy. In any case, the destitute of Sydney would apparently never miss the Sydney General Poor Relief Fund if it wound up its operations forthwith.[16]

While The Worker disagreed with the existence of the fund on financial grounds, the Socialist paper, The International Socialist, disagreed with the existence of the fund not so much on financial grounds as on ideological grounds.

We have once before called the attention of the workers to the degrading appeals constantly launched through the capitalist press for old clothes and old boots for the ‘Sydney General Poor Relief Fund’ and other similar charities. A really revolting appeal is now being made by a person signing himself Rothwell, asking, among other things, for “donations of left off clothing and boots”; and offering on the lines of the now infamous ”Charity Organisation Society” of London a book of tickets in exchange for £1 subscription — such tickets “to be given to applicants for relief instead of giving money or food.” Mr. Rothwell heads his appeal with the words: “There is something good even in the most depraved.” How do you like it, you workers of the “workman’s paradise?” this idea that because you fall on evil times, and fail to climb the tree of success (up which swarm the politicians, the employers, and the land owners, who live on your labor) therefore you are depraved, and stand in need of soup tickets and tracts? But worse lies behind. On turning over this precious appeal, we find that the Hon. G. S. Beeby, Minister for Instruction, has emphasised the fact that the principles of the Fund were about the only ones that really promised to reach the root of giving charity without pauperising the recipients.[17]

The organizers and attendees of these fundraising activities, which these newspapers had criticized, were led to believe that the primary purpose of the SGPRF was to provide “Xmas” dinners for the poor.[18] At Christmas time, the SGPRF management reported via the newspapers that they had ‘distributed parcels of groceries containing everything necessary for all requirements for the families of the poor for a week.’[19]

Who were these philanthropically minded people who ran this charity?

There were a few names available for those who were involved in the organization of the charity. Three names, in particular, were prominent and in ascending order of responsibility for the charity’s actions were Bertie Elvena Hurburgh, ET Perry and Thomas Lovell Rothwell; they were described respectively as a concert organizer, a Collector, and an Honorary Director for the SGPRF.

Bertie Elvina Hurburgh – Concert Organizer for the SGPRF

Bertie Elvena (often spelt Elvina) Hurburgh was born 11 May 1881 in Hobart, Tasmania, and died 18 December 1961.[20] She was the daughter of William Ringrose Devereux Hurburgh, wood and coal merchant and fruiterer and Emily Elvena, nee Young.[21] Bertie was an accomplished musician, composer and teacher. She came to public attention in 1904, when she organized what was regarded as a successful concert for the SGPRF in Sydney, in which she played and was assisted by other musicians.[22] In 1906, she performed with others in the Balmain Town Hall[23] with the proceeds going to the SGPRF.[24] In 1911, she contributed a musical item at the ‘Sydney annual eisteddfod exhibition and May Fair’ which was held in aid of the SGPRF. The occasion was opened by Lady Cullen and in attendance was the Minister for Education and Mr Rothwell (director).[25] In September 1912, Bertie married Thomas Lovell Rothwell at St Mary’s Church of England, Balmain;[26] for most of her married life she was a teacher and she and Thomas had no children. From about 1921 to 1928, she was the musical directress of the Stratford College at Lawson.[27]

E T Perry – Collector for the SGPRF

The identity of ‘Mr E T Perry’, the articulate collector of the SGPRF from early in 1909 until January 1914, was never clearly revealed. Indeed, when the police showed an interest in the legitimacy of the fund, their efforts to trace the collector in the country failed.[28]

The collector known as ‘Mr E T Perry’ is most likely Ernest Thyre Perry, the son of the Rev and Mrs Charles Stuart Perry, St Jude’s Carlton. He was born in Melbourne on 27 November 1873 and died in Wollongong on 6 March 1937.[29] He was educated at Melbourne Grammar School[30] and in December 1890, after the death of his father, he went with his family to England, where he studied at St Catherine’s College, Oxford, and became proficient in Greek, Latin and French. He returned to Australia from Britain in March 1896 and worked at Prahran College, commencing in early 1897,[31] and by 1898, he was also seeking work as a private tutor in Moe and Taralgon.[32] In October 1900, Perry took a job as a lay curate at St John’s Mudgee[33], and this position lasted nine months. At the end of this time, he returned to Morwell and sought to establish himself again as a tutor and as the Principal of Morwell Grammar School.[34] In June 1903, he married Elizabeth Holmes of Mudgee [35], and in December 1903, he sold his furniture[36] and moved to NSW to take up a position at Kingswood College, Bondi.[37] In 1904, their son Stuart Ernest Perry was born[38], and while little is heard of Perry at this time, it is known that he was resident at the Kingswood College in Bondi. After 1904, there were few advertisements for Kingswood College, with the last being in 1908, indicating that Ernest T Perry was still the principal at the time.[39] It seems that the College struggled and ceased around 1908; Perry needed another source of income and in June 1908, he took the morning service at Sylvania Church of England.[40]

The next reference to Mr E T Perry is in October 1911, when he had begun collecting funds for the SGPRF,[41] though it is clear he had been working for the SGPRF in Sydney from around January 1911. His practice was to see that the local newspapers knew he was in town collecting on behalf of the SGPRF[42] so that his presence in the district was noted. At the end of his time in a district, he issued a thank you through the newspaper to the local community for their support.[43]

The Burrangong Argus (NSW), 17 Aug 1912, 1

By early 1914, he seems to have ceased collecting for the SGSPF, but later that year, he was involved in a fundraising concert in Mt Keira at which he spoke. It was said of the occasion that “The juvenile portion of the audience, as well as the adults, were very much amused at the account of some of the lecturer’s experiences, particularly with those with the canine animals”.[44] In 1915, he was taking services at Thirroul and Woonona Church of England,[45] on 11 December 1917, he was in Wollongong and was granted a hawker’s license[46] and so supplemented his income by selling goods from door to door.[47] In 1919, he advertised his services as a tutor.[48]

The timetable of Ernest Thyr Perry’s life seems to fit the identification of ET Perry as being: the collector of the SGPRF, the Oxford man, the son of a Melbourne clergyman who sought to be headmaster of two Grammar Schools in Victoria and one in Sydney, NSW, and who ended his days as a Tutor and a Hawker of goods door-to-door. This tentative conclusion is made certain in the following narrative in a Morwell newspaper dated 20 May 1910. In it the writer, a resident of Morwell, describes a trip to Sydney and gives an account of people he met from Morwell who had moved to Sydney. He said …

Another former resident of Morwell I met was Mr E T Perry, who had a private school in Morwell for a short time, and was a lay reader connected with [the] local Church of England. He informed me that he had had his “ups and downs” since he left Morwell, but it was hard to say whether he was up or down at the present time. He had just taken a job of canvassing for an institution to relieve the poor and needy, and his prospects are not too assuring.[49]

The identification of Ernest Thyr Perry with the collector Mr ET Perry is complete. Was Perry involved in the con of making money from fraudulent requests for funds, which he knew were not really for the poor? It seems he took the job in hard times when he was struggling to support himself and his family. He was open about his work as he was about to begin it in 1910, and in writing an account of his work in 1914 when he concluded. There is nothing in his background or his actions that indicates he was anything other than one who needed an income and so diligently collected funds on behalf of what he thought was a legitimate cause. After deducting his salary and expenses, he passed the collected money on to Thomas Rothwell, the most prominent promoter of the fund.

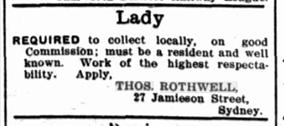

Thomas Lovell Rothwell – Director of the SGPRF and conman

Thomas Lovell Rothwell[50] (pictured below in gaol photo dated 1904) was born in Camden, NSW, in 1885 to William John Rothwell and Susan Jessie Gibson. He had two brothers, William Taylor, born in 1883, and Stanley Gibson, born in 1887. He married Sylvia Clarice Hall (1871-1910) in 1904 and then, in 1912, after Sylvia’s death, he married Bertie Elvena Hurburgh (1881-1961).

Throughout his life, Rothwell was variously self-described as TW Rothwell, TV Rothwell, SW Rothwell,[51] Thos Rothwell, V Rothwell,[52] Thomas Lovell Vickers Rothwell[53] and T Vicars Rothwell, and even as Thomas Lovell.[54] He designated himself variously as a tram driver,[55] clerk, accountant, Business Manager and in connection with the SGPRF as Gen. Director and later as Hon Director, but little other information was given about him and his role. The use of so many variants of Rothwell’s name immediately suggests something very suspect was going on with him.

In fact, in his lifetime, Rothwell managed to amass a significant criminal record for theft and deception, beginning in 1901 when he was sixteen. He was charged with stealing and received 3 months’ hard labour, but the sentence was suspended as it was his first offence. One week later, he was in court again, and when arrested, he gave his profession as a draper. He was charged with theft for he had in his possession ‘44 linen handkerchiefs, five silk handkerchiefs, seven pairs of kid gloves, six pairs of cuffs, sixteen silk ties, and four pairs of socks, reasonably supposed to have been stolen’.[56] He received a sentence of a ‘fine of £5, or, in default, imprisonment for two months with hard labor’; [57] he paid the fine.

Three years later, in 1904, aged 19, he was charged under the name of Thomas Lovell with four counts of false pretences by passing bad cheques to retailers. He was found guilty in three of the cases and was to serve two years with hard labour on each of the three counts, concurrently;[58] he was released from Goulburn Gaol on 29 January 1906.[59] In sentencing him, the judge had said, ‘you appear to have entered upon a career of wholesale swindling.’[60]

1909-1915 Rothwell’s scam

The judge’s words were prescient, as it would appear that Thomas L Rothwell alias ….., alias….. was a con man who managed to persuade people to give money to the SGPRF, the proceeds of which he himself appropriated. After Rothwell completed his gaol sentence in January 1906, nothing was heard of him for several years. This changed when, in November 1909, an advertisement appeared under his name appealing for support for a Christmas lunch run by the Sydney General Poor Relief Fund. It was an appeal for funds to provide for those who would otherwise have a miserable Christmas. After Christmas in 1909, there followed an announcement ‘thanking all those who by their assistance and hearty co-operation …. so largely contributed to the success of the work of the fund’.[61] In May 1910, a May Fair in aid of the SGPRF was held. The hall had stalls supervised by lady helpers, and when Rothwell opened the fair, [62] he expressed the hope that the numerous casual subscribers to the fund would join the permanent ranks.’ At the fair in the following year, which also incorporated an eisteddfod, Rothwell promoted the work of the fund, even talking of its expansion, for he mentioned that as soon as ‘the institution got a building of its own it would be self-supporting’.[63]

This 1913 example of his approach to communication with supporters through the newspapers is as deceptive as it is obsequious:[64]

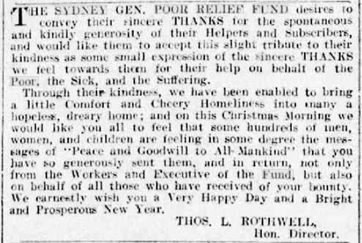

At the same time as the various fundraising events were organized by Rothwell with the assistance of kind-hearted and trusting supporters, he was seeking collectors who would collect funds in country areas on behalf of the SGPRF. E.T. Perry had done this from around 1911 until 1914, but Rothwell intensified his efforts in 1912 to raise funds from the canvassing of country towns. A series of advertisements began to appear in local country newspapers seeking collectors for the following areas: [65] Tamworth, Jerilderie, Urana, Hay and Molong. The collectors he sought were Ladies, residents of and well known in the collection area, a criterion that would probably get a sympathetic response as they knocked on doors, and who would not ask him too many difficult questions about the use of the money.

Rothwell continued his fundraising concerts and the like up to 1914 when someone realized that all was not as it was promoted to be.

1915: REMARKABLE SWINDLING. IMPOSTOR GOES TO GAOL. FATHOMLESS HYPOCRISY.

In April 1915, The Sun newspaper reported on the affairs of the SGPRF when ‘Thomas Lovell Rothwell, aged 30, was charged with having on or about April 14 imposed upon Samuel Nettleton by fraudulent representation. He pleaded guilty.’[66]

Mr Robison, of the Crown Law Department, said that Rothwell was the honorary director of the Sydney General Poor Relief Fund, which had been in existence for years. There was also an “honorary treasurer,” who received £25 or £50 a year. Last April, the attention of the Auditor-General was directed to the Institution, and an officer was deputed to go through the books. Only one book was obtained, and there was practically nothing to check the entries in the book. Everything was in disorder, Mr Robison explained, but it was discovered that a man was in the country who had in two or three years collected £800 for the Institution. About £400 had been kept by the collector for salary, commission, and travelling expenses, and the balance, nearly £200, had been sent to Sydney and applied by Rothwell in payment of a debt incurred. Roth[e]well said[.] in the control of a newspaper run by the society two years before. Rothwell was responsible for that debt. So of the £600 collected, the poor of Sydney received nothing. Efforts to trace the collector in the country failed. Rothwell was advised to give up the organisation, and in a letter to the Auditor-General on July 11, he gave particulars of the committee (well-known Sydney people, Mr Robison explained, who had unfortunately lent their names to the organisation, while knowing little about it), and stated that no balance-sheet of the fund had been published. He said that he had no objection to the fund closing down, as it had caused him annoyance and expense. He added that but for the way in which the police had heckled him it would have ceased long ago. He had had enough police inquiry to rouse the obstinacy of any man, especially as he had done nothing wrong and had tried to help others. The fund’s writing paper was headed,

“There is something good in even the most depraved. We ask your help and sympathy to find and develop this goodness [for] God and man.“

Nothing, Mr Robison continued, was done until recently, when Rothwell told him that all collectors had been given notice to cease. Early in April, Rothwell wrote to Detective Jordan stating that the fund had voluntarily ceased its work. Some days later Roth[e]well wrote to the Crown Solicitor at his present address, pleading for assistance to the fund, pointing out that serious indeed was the position of a large number depending on them, and that unless aid was received they could see no alternative for the terrible sufferings of the poor, helpless, and sick being not only continued but increased. That letter was handed to the Crown Law Office, and information was received about a gentleman having sent a cheque to Rothwell this month.

“Inquiries,” went on Mr Robison, “brought to light the following letter, which had been received by a firm of bookmakers: —

As you will see by the enclosed voucher, £1 was placed on Pedestrian. As he didn’t start, I presume the £1 is returnable; therefore place It as under, together with the £4 enclosed:— City Tatt’s Cup, Saturday. April 17, Necktie, 1, 2. 3 (place), £5.

We then discovered that the cheque referred to had been sent to the book maker, and in view of the facts I have no hesitation in asking that you impose the maximum penalty of six months. When arrested, a cheque for £1 1s from Mr King, S.M., and another cheque for £2 2s were found on Roth[e]well.

The fact that one cheque was sent to a bookmaker to put on a horse is sufficient evidence as to what had become of the other contributions. The police have not been able to trace anybody who has received financial assistance from this institution. Old clothes have been given away and a grocery receipt has been discovered, but what became of the groceries we cannot tell.

Mr Barnett in sentencing Rothwell to six months imprisonment, said ‘that he was extremely fortunate that the case did not go to a higher court. Six months was an extremely light punishment for what was really fathomless hypocrisy‘.[67]

In this sorry history, what assessment is to be made of the three main characters: B E Hurburg, E T Perry and Thomas Lovell Rothwell?

My impression is that Bertie Hurburg was genuinely seeking to help the poor. She got caught up with a conman who misled both the community and herself; she was deceived about the man she was to marry.

Ernst Thyre Perry took on the job of collecting funds for the SGPRF in hard times when he was struggling to support himself and his family. There is nothing to suggest anything other than he genuinely believed he was collecting funds on behalf of what he thought was a legitimate cause.

Thomas Lovell Rothwell was a fraudster who deceived his own wife, his charity collector and those who contributed to the SGPRF. When apprehended and put on trial for fraud, he was given a chance to change his life’s direction, with the magistrate giving, in the circumstances, a light sentence. At the end of six months, his prison sentence served, Rothwell was released from prison.[68] Would Rothwell now change and leave his dishonest ways, or would he revert to making a living by dishonest means? The answer to this question is rather complex and tricky, which is no real surprise for a conman, and it deserves a post of its own.

Paul F Cooper

Research Fellow, Christ College, Sydney

Paul F Cooper, Thomas Rothwell and the Sydney General Poor Relief Fund, Philanthropy and Philanthropists in Australian Colonial History 25/10/2025 available at Colonialgivers.com/2025/10/25/ Thomas-rothwell-and-the-sydney-general-poor-relief-fund/

[1] SMH, 22 November 1909, 1.

[2] SMH, 23 Nov 1909, 2.

[3] SMH, 24 Nov 1909, 7.

[4] SMH, 7 December 1911, 10; The Daily Telegraph (Sydney, NSW), 21 Nov 1914, 2.

[5] SMH, 18 Dec 1909, 17.

[6] The Daily Telegraph (Sydney, NSW), 30 Apr 1910, 11.

[7] The Ulladulla and Milton Times (NSW), 30 Dec 1911, 8.

[8] Their marriage took place on 23 July 1912. SMH, 14 Sept 1912, 7; The Berrigan Advocate (Cobram, NSW), 27 Sept 1912, 5.

[9] The Sydney Morning Herald (NSW), 28 Dec 1909, 2.

[10] Queanbeyan Age (NSW), 25 Feb 1913, 4.

[11] Queanbeyan Age (NSW), 25 Feb 1913, 4.

[12] Queanbeyan Age (NSW), 25 Feb 1913, 4.

[13] A Psalm of Life by Henry Wadsworth Longfellow

[14]The Latin saying means ‘never despair’. Queanbeyan Age (NSW), 25 Feb 1913, 4.

[15] The Sun (Sydney, NSW), 25 Apr 1915, 4.

[16] The Worker (Wagga, NSW), 8 September 1910, 22.

[17] The International Socialist (Sydney, NSW), 12 Aug 1911, 1. Sir George Stephenson BEEBY (1869 – 1942).

[18] SMH, 24 November 1909, 7.

[19] SMH, 24 Dec 1910, 9.

[20] New South Wales BDM 4428/1962; Find a Grave, database and images (https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/174292555/bertie_ellvena-rothwell: accessed February 27, 2025), memorial page for Bertie Elvena Rothwell (unknown–18 Dec 1961), Find a Grave Memorial ID 174292555, citing Eastern Suburbs Memorial Park, Matraville, Randwick City, New South Wales, Australia.

[21] Baptismal Record, Hobart 2615; SMH, 11 Nov 1927, 12.

[22] SMH, 15 Dec 1904, 5.

[23] Balmain Observer and Western Suburbs Advertiser (NSW),19 May 1906, 3.

[24] SMH, 28 December 1907, 2; 8 February 1908, 5; 12 March 1910, 2.

[25] SMH, Fri 26 May 1911, 10.

[26] SMH, Sat 7 Sept 1912, 14.

[27] Sunday Times (Sydney, NSW), 1 July 1928, 19.

[28] Sun (Sydney, NSW), 24 April 1915, 5.

[29] Wollongong Cemetery inscription – though date given in Obituary in Sunday 7 March 1937, South Coast Times and Wollongong Argus (Wollongong NSW), 12 March 1937, 15.

[30] South Coast Times and Wollongong Argus (NSW), 20 Apr 1934, 12.

[31] Prahran Chronicle (Vic.), 30 Jan 1897, 4.

[32]The Narracan Shire Advocate (Vic.), 4 June 1898, 2.

[33] Morwell Advertiser (Morwell, Vic), 12 Oct 1900, 3.

[34] Mudgee Guardian and North-Western Representative (NSW), 9 May 1901, 12; Traralgon Record (Traralgon, Vic), 28 May 1901, 2; The Argus (Melbourne, Vic), 18 July 1903, 9.

[35] Morwell Advertiser (Morwell, Vic), 19 June 1903, 2.

[36] Morwell Advertiser (Morwell, Vic), 18 Dec 1903, 2.

[37] Mudgee Guardian and North-Western Representative (NSW), 3 Mar 1904, 11.

[38] The Daily Telegraph (Sydney, NSW), 30 July 1904, 5.

[39] The Daily Telegraph (Sydney, NSW), 18 Jan 1908, 7.

[40] Evening News (Sydney, NSW), 13 June 1908, 16.

[41] The Shoalhaven Telegraph (NSW), 4 Oct 1911, 6.

[42] The Burrangong Argus (NSW), 3 Aug 1912, 2.

[43] The Burrangong Argus (NSW), 17 Aug 1912, 1.

[44] Illawarra Mercury (Wollongong, NSW), 2 Oct 1914, 2.

[45] South Coast Times and Wollongong Argus (NSW), 8 Oct 1915, 10.

[46] Illawarra Mercury (Wollongong, NSW), 14 Dec 1917, 7. His profession on his death certificate is “Hawker”.

[47] Illawarra Mercury (Wollongong, NSW), 12 Mar 1937, 7.

[48] South Coast Times and Wollongong Argus (NSW), 31 Jan 1919, 10.

[49] Morwell Advertiser (Morwell, Vic), 20 May 1910, 3.

[50] Lovell is sometimes spelt Lovel.

[51] SMH, 26 May 1910, 10.

[52] The Gundagai Independent and Pastoral, Agricultural and Mining Advocate (NSW), 7 Sept 1912, 3.

[53] Australian Electoral Rolls 1903-1950, 1913 Balkan

[54] The Ulladulla and Milton Times (NSW), 30 Dec 1911

[55] Co-operator (Sydney, NSW ), 19 Dec 1912, 8.

[56] The Daily Telegraph (Sydney, NSW), 19 July 1901, 8.

[57] The Daily Telegraph (Sydney, NSW, 19 July 1901, 8; https://search.records.nsw.gov.au/permalink/f/1e5kcq1/INDEX2088207

[58] NSW Police Gazette, 24 August 1904, 341.

[59] New South Wales Police Gazette and Weekly Record of Crime (Sydney), 7 Feb 1906 [Issue No.6], 53.

[60] The Australian Star (Sydney, NSW) 17 June 1904, 3.

[61] SMH, 28 Dec 1909, 2.

[62] SMH, 26 May 1910, 10.

[63] SMH, 26 May 1911, 10.

[64] The Daily Telegraph (Sydney), 25 Dec 1913, 10.

[65] The Tamworth Daily Observer (NSW), 16 May 1912, 3; Jerilderie Herald and Urana Advertiser (NSW), 17 May 1912, 2; The Riverine Grazier (Hay, NSW), 17 May 1912, 3; Molong Express and Western District Advertiser (NSW), 18 May 1912, 11.

[66] The Sun (Sydney, NSW), 25 Apr 1915, 4.

[67] The Sun (Sydney, NSW), 25 Apr 1915, 4.

[68] The Sun (Sydney, NSW), 25 Apr 1915, 4.