John Barnett (1837-1905) was born in Stepney, Middlesex, England, on 21 February 1837, the son of John Barnett (Senior) (1810-1858), Grocer and Sugar Refiner and Ann Eliza Winkworth (1807-1842).1 In December 1859, John married Janet Gowanlock Smith (1840-1927) at Waverley, Sydney, and they were to have eight children, four of whom lived to adulthood.

John’s parents, together with his 6-year-old sister Elizabeth and his 3-year-old self, had emigrated from England to Sydney in New South Wales (NSW), arriving on the Ann Gales on 12 July 1840. His mother, Ann Eliza, died not long after they arrived in Sydney, and John Snr married Janet Scot Smith (1826-1872) in 1843. The family had been sponsored by William Knox Child as part of Child’s attempt to set up a sugar refining business in NSW. The Ann Gales had on board the Child family and other sponsored workers in the sugar trade,2 a steam engine, sugar house plant and machinery for the Australian Sugar Company.3 This was a serious attempt at commencing a ‘sugar trade’ business in the Colony of NSW, and Child had invested some £20,000 in this project.

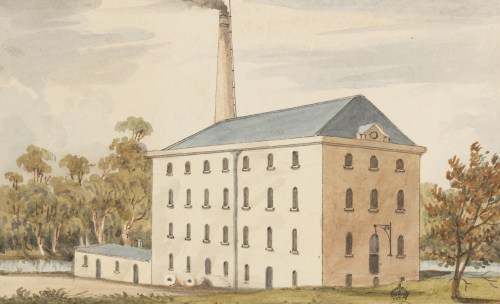

A sixty-acre site was chosen at the Cook’s River on Robert Campbell’s Canterbury Estate, and a mill was constructed there, and a town was built for the workers.4 By late 1842, sugar had been refined and was ready for market. It was reported that ‘this company is now in operation and will be enabled to supply the whole of the Australian Colonies with refined sugar at the following prices … ’.5 A dispute soon broke out among the partners, which threatened the viability of the company. Then, in 1843, Edward Knox took over as manager, and the company prospered, becoming known as the Colonial Sugar Refining Company (CSR) in 1855.6

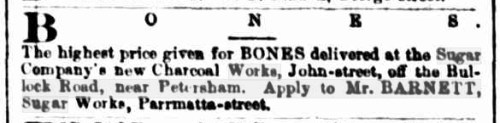

Over time, the Canterbury site was found to be too expensive in terms of cartage, and the works were moved to Parramatta Street West, Sydney,7 and it was here, on 16 January 1851, that John8 began work and where he was to be eventually appointed manager of the works in December 1877.9 Part of John’s role at the Parramatta Street West sugar mill was to organise and oversee the purchase of animal bones.10 These bones, along with some residual and still attached flesh, were stockpiled at the mill before being fired and converted to charcoal from which gas was distilled to light the buildings and refine the sugar. Both the decaying flesh and the derived gas produced a noxious smell to which the local residents understandably complained. This led to council inspections and interviews of management; the sugar mill was required to amend its practices. Barnett was involved in this process and, as part of the solution, the company produced its charcoal at a dedicated Charcoal Works in Petersham.11

| THOSE HORRIBLE SMELLS12 A Sydney Ballad, sung by Mr. Beaumont Read. AIR – Those Beautiful Bells. | |

| Those horrible smells, those horrible smells, Silently, solemnly, tolling our knells; From the Glebe Island and over the flood Wafting the perfumes of slaughter and blood. One single puff of it’s more than enough of it; Only a sniff of it sickens – repels. Nameless corruption, death, and destruction Reign in the breath of those horrible smells. | Perfumes astounding us, ever surrounding us, Causing the most unaccountable gripes; Heartily sick of it, we from the thick of it Fly to the solace of brandy and pipes. Vapours pursuing us, killing, subduing us, Acting alike on the snobs and the swells. Poor aristocracy! Wretched democracy! Victims alike to those horrible smells. |

| Why are they ranging, fearfully changing Peace to dejection, joy to despair? Senses olfactory getting refractory, Noses such nuisances never can bear. Try Parramatta-street – now isn’t that a treat? That’s where the man with the sugar-works dwells; Sugar refining, health undermining, Adding his mite to those horrible smells. | Offal and sediment, free from impediment, Poison the region of Blackwattle Swamp. Vain are the “jaw-breakers” used by our lawmakers Sitting in passive and indolent pomp: While they are tarrying, corpses are carrying! List to the tolling of funeral bells! Widows are crying, while husbands are dying, Slain by the breath of those horrible smells! |

It would seem that the promotion was not a sufficient incentive for John to remain at the sugar works, and in January 1878, he left the sugar works and joined in a partnership with ‘Walter Smith & Co’ to form a business that was known as the Albion Tailoring Company.13 The move from managing a sugar refining mill to taking up a partnership working with those who were tailors seems like a significant change and deserves comment.14

The Albion Tailoring Company was the trading name of ‘W. Smith and Co’ and this company had passed through many iterations. Originally, this tailoring business was commenced by Henry Isler, but on his retirement, the business became successively ‘Jones and Smith’, ‘Jones, Smith and Curtiss’, ‘Smith and Curtiss’, then ‘W. Smith and Co’.15 In 1866, James Boyd was admitted to the partnership in W. Smith & Co without a change of name, and this partnership continued until 1875, after which it was dissolved. 16 Walter Smith continued in business as a sole partner trading as ‘W. Smith & Co’ (Albion Tailoring Company) until 1 January 1878, when John Barnett became a partner.17 In July 1883, William McKenzie became a partner18 and on 30 March 1884, Smith retired. The Albion Tailoring Company was carried on by the partnership of John Barnett and William McKenzie.19 In 1892, Walter Smith repurchased the business, and John Barnett retired.20

This complicated business history is matched by the complications of the Smith and Barnett family history. Walter Smith, of W. Smith & Co, was father-in-law to John Barnett, and Janet Scott Smith was both Walter Smith’s sister and John Barnett Senior’s second wife. Thus, Janet Scott Smith, now Janet Scott Barnett, was also John Barnett’s stepmother, while John Barnett’s wife, Janet Gowenlock Smith, was the niece of Janet Scott Barnett (nee Smith)! So, the explanation for John Barnett’s move from a sugar refinery to a company concerned with tailoring is, in a word, ‘family’. He had become a partner in a family business which had enjoyed and would enjoy commercial success for many years to come.

Outside of Barnett’s working life, he was involved in several organisations and causes and in those, he was usually a worker rather than a leader. As a worker, he was involved in the Penny Bank and the Labour Home as well as with the Temperance issue. As a leader, his preeminent commitment and leadership were seen in his involvement with the commencement and growth of St Barnabas Anglican Church, Parramatta Street, Sydney.

Penny Bank

An account of Barnett’s life says that he, with “Messrs, JH Goodlet, JS Harrison, and JP Croft, started a penny savings bank in connection with St Barnabas Church, and that he took an active part in its management until it was closed…”.21 This statement is a mixture of fact and fiction. The Penny Bank referred to is the Glebe and Parramatta Road Penny Bank, which was commenced and run from the St Barnabas Church building, beginning in 1862 and closing in 1900.22 JH Goodlet was a founding secretary, but there is no record of JS Harrison (probably a mistake for GR Harrison), nor of JP Croft being a committee member. 23 While no evidence has been found for the involvement of John Barnett, GR Harrison or JP Croft in the Penny Bank, all these men were actively involved at St Barnabas, so it is likely that they were involved with the Penny Bank associated with St Barnabas. In fact, in 1871, Barnett was the auditor of the accounts of the Bank.24

Labour Home

The 1890s proved challenging times in NSW with difficult business conditions, high unemployment and low wages, which together led to a significant humanitarian crisis. The commencement of the Church Labour Home in 1891 by the Rev JD Langley, a prominent Anglican clergyman, sought to provide employment and shelter for unemployed men.25 Barnett’s obituary said of him that ‘he was a great worker for the Labour Home, Pyrmont’.26 It has not been possible to establish the accuracy of this claim; however, given that the Labour Home was commenced through the work of Langley, an Anglican, as was Barnett, and as it utilised the support of volunteer workers, such a claim is likely to be true.

Temperance

It was also claimed in Barnett’s obituary that Barnett was ‘also [a great worker] for all temperance movements’.27 The most conspicuous example of this commitment was his involvement in The Dawn of Freedom Lodge No 104, I.O.G.T (Independent Order of Good Templars), which was formed in October 1878,28 and met at St Barnabas.29 By 1881, Barnett was the D.G.W.C.T (Deputy Grand Worthy Chief Templar) of the chapter of the Good Templars of the Dawn of Freedom Lodge.30 Through the Good Templars, Barnett supported his minister, Rev Joseph Barnier, in his temperance and local option views. Barnier, who was also a Good Templar, had delivered a sermon at St Andrews Cathedral before the Church of England Temperance Society; Barnett organised for him to also deliver this sermon at St Barnabas’ Church.31

St Barnabas

John Barnett “took great interest in church matters”.

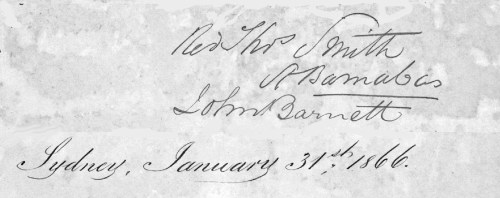

He, with the late Canon Smith, held the first service in connection with St Barnabas‘ Church in a small room in the hotel at the corner of Parramatta Street and Hay Street ‘…. ‘They afterwards took a larger room at the University Hotel, Glebe. They then arranged the building of the present church in 1858.”32

In 1860, a few years after the opening of the church building, it was found that a gallery was needed to cope with the increased number of those attending the church services. Barnett was elected to the committee to which this task was delegated.33 He was both the contact for and was involved in the following matters for the church: 1863, inserted a notice in the newspaper seeking to employ a Sexton for St Barnabas Church;34 1883, was Vice President of the Singing Class;35 1889, the Young Men’s Literary Society;36 the Sunday School Festival;37 Treasurer of the Barnier Memorial Fund;38 1897, he was a founding committee member of the St Barnabas’ Old Boys Union whose aim was to have an association of gentlemen who belonged to the school.39 Barnett served as a Church Warden from at least 1865 to 189040 and then as the church’s auditor in 1902 and 1903.41 He also served as a member of the Synod of the Diocese where he represented St Barnabas from 1866-189242 and he was also a Committee member of the St Barnabas Church Society 1866-1887and 1887 as Treasurer.43

In his life, John Barnett was not a prominent leader or extensive contributor to the development of the colony of NSW. In many respects, his life was unremarkable yet important. He represents the great number of citizens of the colony who lived, worked, raised families and in doing so contributed to the building of the colony. The investment of his time and dedication to the development of St Barnabas Anglican Church is today, along with the investment of many others since its formation, still bearing fruit in Christ’s service.

Paul F Cooper, Christ College, Burwood, NSW

The appropriate way to cite this article is as follows: Paul F Cooper, John Barnett (1837-1905) an unremarkable but important life, Philanthropy and Philanthropists in Australian Colonial History, available at https://colonialgivers.com/2025/09/07/john-barnett-1837-1905-an-unremarkable-but-important-life/

- John Barnett in the London, England, Church of England Births and Baptisms, 1813-1924. ↩︎

- New South Wales, Australia, Assisted Immigrant Passenger Lists, 1828-1896, July 1840, Ann Gales; The Sydney Gazette and New South Wales Advertiser (NSW), 14 July 1840, 2. ↩︎

- The Sydney Gazette and New South Wales Advertiser (NSW), 14 July 1840, 2. ↩︎

- SMH, 12 Aug 1933, 9. ↩︎

- SMH, 12 Aug 1933, 9. ↩︎

- The Daily Telegraph (Sydney, NSW), 19 Jan 1924, 17. ↩︎

- SMH, 12 Aug 1933, 9. ↩︎

- SMH, 3 Jan 1878, 9. ↩︎

- The Sydney Mail and New South Wales Advertiser (NSW), 22 November 1905, 1310; The last notice in the newspapers that he was at the sugar works is the SMH, 26 June 1877, 12. ↩︎

- Sydney Mail (NSW), 19 Nov 1870, 4; SMH, 8 Aug 1871, 8. ↩︎

- Sydney Mail (NSW), 19 Nov 1870, 4. ↩︎

- Sydney Punch (NSW), 17 Sept 1875, 2. ↩︎

- SMH, 3 Jan 1878, 9. ↩︎

- SMH, 3 Jan 1878, 9. ↩︎

- SMH, 1 July 1864, 7. ↩︎

- SMH, 15 Oct 1875, 1. ↩︎

- SMH, 3 Jan 1878, 9. ↩︎

- The Sydney Daily Telegraph (NSW), 6 Sept 1883, 1. ↩︎

- The Daily Telegraph (Sydney, NSW), 21 Apr 1884, 7. ↩︎

- The Daily Telegraph (Sydney, NSW), 20 Oct 1892, 1; 12 Apr 1893, 6. ↩︎

- Sydney Mail and New South Wales Advertiser 22 November 1905, 1310. ↩︎

- Paul F Cooper. Penny Banks in Colonial NSW: banking that sought to serve. Philanthropy and Philanthropists in Australian Colonial History, June 25, 2018. Available at https:/colonialgivers.com/2018/06/25/penny- banks- in- colonial- nsw-banking- that- sought- to- serve ↩︎

- Paul F Cooper. More Valuable than Gold, (Eider Books, The Ponds, 2015), 75. ↩︎

- SMH, 10 Aug 1871, 5. ↩︎

- Paul F Cooper. Church Labour Home Philanthropy and Philanthropists in Australian Colonial History, February 20, 2017. Available at https://phinaucohi.wordpress.com/2017/02/20/the-church-labour-home/ ↩︎

- Sydney Mail and New South Wales Advertiser, 22 November 1905, 1310. ↩︎

- Sydney Mail and New South Wales Advertiser, 22 November 1905, 1310. ↩︎

- SMH, 22 July 1880, 6. ↩︎

- SMH, 30 May 1879, 5. ↩︎

- Evening News (Sydney, NSW), 23 Nov 1881, 3. ↩︎

- SMH, 4 Feb 1882. ↩︎

- Sydney Mail and New South Wales Advertiser, 22 November 1905, 1310. ↩︎

- Empire (Sydney, NSW), 11 July 1860. 8. ↩︎

- SMH, 7 Jan 1863, 8. ↩︎

- The Daily Telegraph (Sydney, NSW), 26 Jan 1883, 2. ↩︎

- The Daily Telegraph (Sydney, NSW), 28 Nov 1889, 6. ↩︎

- SMH, 16 Nov 1889, 2. ↩︎

- SMH, 14 Nov 1889, 4. ↩︎

- SMH, 1 June 1897, 3. ↩︎

- Illustrated Sydney News (NSW), 16 May 1865, 7; Empire (Sydney, NSW), 29 Apr 1867, 5; SMH, 20 Apr 1868, 2; 9 Apr 1869, 2; 6 April 1880, 6; 7 Apr 1888, 12; 31 Oct 1889, 4; 11 Apr 1890, 3. ↩︎

- SMH, 25 Jan 1892, 5; 11 Apr 1890, 3; Watchman (Sydney, NSW), 2 May 1903, 7. ↩︎

- SMH, 14 Dec 1866, 3; Empire (Sydney, NSW), 22 Aug 1867, 5; Sydney Mail (NSW), 24 Apr 1869, 11; SMH, 17 July 1872, 3; 5 February 1874, 3; 21 Apr 1875, 4; SMH, 14 June 1876, 8; 25 June 1879, 6; 22 June 1881, 3; Evening News (Sydney, NSW), 12 Dec 1882, 3; The Sydney Mail and New South Wales Advertiser (NSW), 12 July 1884, 78; SMH, 19 Dec 1885, 11;12 November 1890, 8; 5 Aug 1891, 4; 25 Jan 1892, 5. ↩︎

- Sydney Mail (NSW), 8 Sept 1866, 7; SMH, 24 Jan 1877, 5; The Daily Telegraph (Sydney, NSW), 19 Jan 1887, 4. ↩︎