Walter Vincent alias Brown was a member of the opportunistic profession of the sweet-talking donation fraudster. He presented himself as a genuine collector of subscriptions for various charities, but he was not.

Obtaining funding for the work of the various nineteenth-century philanthropic organisations was always a challenge. There was little government financial assistance available, and the various charitable organisations were dependent upon the generosity of the public for financial support. To gain that support, the many charities that wished to collect money from the public engaged in a number of activities and strategies. Prominent among their activities was the public annual meeting, often chaired by a socially important person, where the activities of the organisation were reported and supportive resolutions passed. At the meeting, someone, usually the committee secretary, would read a report detailing what had been achieved in the past year, often giving encouraging examples of success and underlining the difficulty of the task which the charity had undertaken. Such reporting made the committee that ran the charity accountable to the public and to its subscribers. It also showed what had been achieved through public financial support, educated the community on the continuing need for the charity, and gave hope for success in the future, so that there might be continued interest and increased financial support given by individuals. These meetings were often widely reported in detail by the press, which devoted considerable space to them.

During the 1890s through to the first decade of the 1900s, the colonies of Australia experienced a severe economic depression. Businesses reported a slowness in trade, a drop in profits, the need to shed workers and in the case of many, through indebtedness and an inability to service loans, to declare bankruptcy. On the personal front, and as a result of reduced income, this meant less food on the table and less access to medical assistance if needed. There was an increase in unemployment as businesses, both large and small, sought to reduce expenditure in an attempt to survive the times.

The plight of those strongly affected by the depression was difficult to ignore. Those who were comfortable financially were concerned about their businesses and the state of the economy, but many also considered how they might assist the needy in the community. The Christian churches and indiviTdual Christians, who saw offering aid as part of their calling to be disciples of Christ, did what they could through personal giving, fundraising through fetes and bazaars and in this way supported the various organisations which were dedicated to the relief of suffering. In the attempt to cover the large and diverse field of need, niche aid organisations, dedicated to particular needs, were formed. These groups usually asked for public assistance in the form of donations of money (often annual) to help service the needs that their society was formed to address.

How were these donations harvested from the willing public? Some donations were spontaneously given and received by the charity as a result of its publicity. Often, in the period immediately after the formation of the charity, those interested in its aims would approach members of the public, friends, neighbours and family for support. For example, when a Ragged School was formed in Glebe in 1862, interested local women residents collected money for the support of the school.[1]

Money was also raised for charities by prominent individuals approaching known wealthy philanthropists and asking for a donation for a specific cause. The philanthropically inclined Thomas Walker[2] and Mary Roberts[3] were examples of this, being approached to support particular charitable purposes, and they often did so with a sizeable donation. But these ad hoc arrangements were not sufficient to provide the level of funding needed by the charities so that they could continue to function and to meet the increasing need.

In order to improve the flow of funding, charities often employed the services of a ‘collector’. Collectors were a common feature of nineteenth-century business life, collecting rents, newspaper subscriptions,[4] payment for bills, receiving accounts for deceased estates and so on. Charities would designate a person as their collector, and that person was then authorised to solicit and receive funds on behalf of their organisation. An early example of this was The New South Wales Philanthropic Society, formed in 1814 for the ‘Protection and Civilization of such of the Natives of the South Sea Islands who may arrive at Port Jackson’,[5] which appointed Richard Jenkins as its collector of annual subscriptions and donations. The Benevolent Society and the Auxiliary of the Bible Society both used a collector, Edward Quin,[6] and he had replaced Sergeant Harry Parsons.[7] Very early in the life of the Benevolent Society, its collector received a commission of five per cent of subscriptions and donations collected [8], but sometimes a collector worked gratis.[9] At its formation in 1823, the Religious Tract and Book Society had a volunteer collector,[10] and in 1826, the Sydney Dispensary was requesting donations to be forwarded to its treasurer to save the expense of the appointment of a collector.[11] The need for a good supply of donations eventually made the appointment of a paid collector for the Dispensary necessary, as it was observed that

collectors, who, gratuitously for the Benefit of the Society, can only devote a Portion of their Time, from their other Avocations, in personally soliciting the Payment of Subscriptions still due.[12]

The return for a collector from an individual charity, even one as well supported as the Benevolent Society, was not sufficient for a living wage, so collectors would canvass for donations and subscriptions for more than one charity. Over time, this led to a reduction in the number of names of people who appeared as collectors.

Across the nineteenth century and until the onset of the depression of the 1890s, a number of names, in turn, dominated the position of collector for public charities as the harvesting of donations and subscriptions became concentrated in the hands of a professional collector. These collectors, and years in which they operated, were Charles Nightingale, 1837 to 1855, Arthur Balbirnie 1855 to 1888, Edward Ramsay 1866 to 1877, and James Druce from 1878 to 1889.[13]

With the onset of difficult financial conditions in the 1890s, the role of collector for public charities became even more challenging. The commissions gained could not have provided sufficient income for anyone, even if they had managed to dominate the charity collection scene. No one assumed the mantle of principal charity collector such as that developed by Nightingale, Ramsay and Druce in their time. Charity collectors still sought donations, but the concentration in the hands of one individual, as had been seen previously, did not take place. A greater emphasis was placed on encouraging volunteers who worked for free, most particularly women, to carry out a larger portion of the work of collection and this began to be seen in organisations such as the Benevolent Society, the Bible Society and the Sydney City Mission. Women were particularly prominent in Hospital Saturday collections, where some 1,200 lady collectors were reported as being active.[14]

There arose two significant challenges to the continued success of collection by a collector on behalf of a charity, and they were donation fatigue and donation fraud. Potentially, both of these issues could erode the public’s charitable support.

Donation Fatigue

With the difficult financial times, there was a call from the charities for more support. In the annual report of the Newcastle Relief Society for 1890, at the early stage of the depression, there is a clear call for more support from its subscribers in the face of increasing need and declining support:

we have had as many cases to relieve as our limited means allowed. We may have greater demands in the coming year, and shall therefore be most grateful for any kind assistance the public or subscribers may afford us. The committee trust that members will be punctual in their payments, in order that relief may be given promptly; and would also be glad to see their present number of subscribers increased, not alone for the object of adding to their finances, but that there may be a larger number of ladies to visit, and relieve each other in their arduous and fatiguing duties. The ladies have continued their regular monthly visits, but owing to decreasing funds so much assistance has not been given as in former years.[15]

Other voices arose, however, that questioned the effectiveness and need for so many charities. The volume of calls upon the charitable purse meant that the most worthy causes often did not get the attention they deserved. One letter to the editor commented on the problem of the bona fides of collectors and the worth of their charities, saying that there was a problem with

the number of collectors who are occupied in calling upon persons with subscription lists for a multitude of objects. A city businessman will probably have as many as 20 callers for charity a week, and the genuine collectors for an institution which may have proved its worth and whose balance sheets are published annually is treated with scant courtesy.[16]

It is evident that donation fatigue had set in, but in addition to donation fatigue there was another problem spawned by the large numbers of those who were collecting on behalf of charities and that problem was donation fraud.

Donation Fraud

The tough economic times, widespread poverty, and a multitude of charities and collectors of donations gave rise to the lucrative field of donation fraud. The opportunistic profession of the sweet-talking donation fraudster appeared amongst the genuine collectors, and they emerged and collected on behalf of their favourite charity – themselves. They presented themselves as genuine collectors of subscriptions for various charities, but they were nothing of the sort.

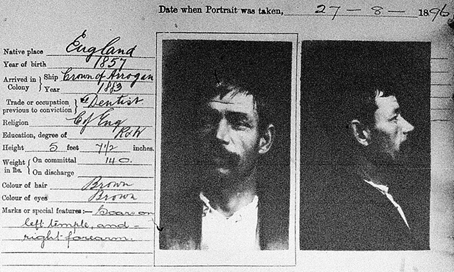

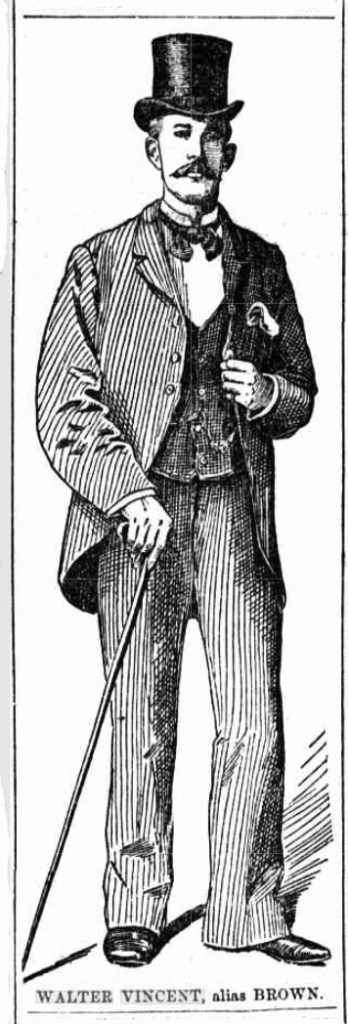

One such fraudster was Walter Vincent alias Brown (which was said to be his actual name), alias King, alias Larkins and alias Lucas.[17] He was an Englishman, born around 1857, who had arrived in the colony of New South Wales in 1883-4 on the ‘Crown of Aragon’, and he was, he said, a dentist. As most of this information comes from Vincent himself, its veracity is unknown, but as far as being a dentist is concerned, the only extraction he did was of other people’s money. He first came to the attention of law enforcement in 1891 when he was arrested while loitering, without apparent reason, in the upstairs corridor of a hotel. Suspected of intending to steal the occupant’s valuables, he was, in October 1891, sentenced to 2 months’ hard labour.[18]

In the next few years, despite this setback to his criminal career, he became very successful at relieving people of their money and was known to police as a ‘monarch among the mendicants’ and dubbed by one of the newspapers as the ‘king of the beggars’. He had managed to convince prominent citizens, business people and lawyers to give money to charities which he said were supporting the unemployed and those in need of financial assistance, but that did not actually exist.[19]

Vincent displayed a good deal of business tact in the way he went about his work, the best evidence for this being that for the three years he carried on his collections, he received upwards of £400.[20] His method was simple. Dressed as a gentleman, he approached people who were well off enough to spare some cash for a charitable cause, a cause that was likely to elicit the sympathy of the potential donor. As he largely targeted the business community, the cause was to assist those who were suffering because of the tough economic situation. He must have had the ‘gift of the gab’, sounding like a genuine representative of the charities for which he was purporting to collect donations. Craftily, and in order to deceive the public, the charities he said he collected for were named by him in such a way as to sound like the names of genuine organisations. He collected, he said, for The Charity Aid Society, an imaginary organisation whose name closely resembled that of the Charity Aid Organisation.[21] He also collected for a bogus City and Suburbs Relief Fund, there having been formerly a genuine City and Suburban Relief Fund.

On receipt of a donation, Vincent would get the donor to record the sum they had given in a book which he kept for this purpose, and he asked them to then initial their record. This was all part of the fraud in that its purpose was to add an atmosphere of accountability to the transaction. It also induced the next prospective victim, upon seeing the book of donation entries all initialled by the donors, to do the same.[22]

His victims included FG Catterhill, manager of the Union Mortgage and Agency Company, from whom he obtained half a crown by false pretences, having stated he was collecting subscriptions for the Charity Aid Society.[23] Using a similar strategy, Vincent obtained £1 from Henry Frederick Chillcott[24] of the Scottish Australian Investment Company.[25] For these and other offences, Vincent was prosecuted and found guilty. That this was the outcome was due to the diligence of Constables JG Brown and AJ Winter, who, at the trial, furnished to the Bench a long and intricate account of his devious ways.[26]

Early in 1896, in a change of approach, Vincent had linked up with a genuine charity known as the Unemployed Organisation of the Destitute Relief Committee, and he was appointed president ‘pro tem’. Shortly afterwards, he was accused of wearing clothes that he had collected on behalf of the Committee. The misappropriated goods were two suits of men’s clothing and two pairs of trousers to the value of £3 18s. Vincent’s explanation was that he had received the clothes and taken them to his home only because the office of the Committee in Albion Street, where they should have been deposited, was closed. He was found not guilty and discharged, not because he was innocent, but due to the fact that the evidence against him was insufficient for a conviction.[27]

Having been convicted of two instances of collecting funds on false pretences, Vincent was sentenced to two periods of 6 months’ hard labour to be served cumulatively at the Darlinghurst Goal, Sydney.[28] After serving his time in gaol, Vincent seems to have disappeared from view. He possibly went interstate, where he was unknown, or perhaps he stayed in New South Wales, assumed a new name (he’d had a lot of practice at that) and continued undetected in his fraudulent ways or perhaps, having learnt that the police were alert to his skills and deception, he amended his ways. Whatever may be the case surrounding the events of his life, hopefully, the persistence of the police in Vincent’s arrest and prosecution restored some measure of public confidence in giving to charitable organisations and causes.

Paul F Cooper

Research Fellow

Christ College, Burwood

The appropriate way to cite this article is as follows: Paul F Cooper. Walter Vincent: Funds, Fatigue and Fraud – an aspect of charity in nineteenth-century NSW Philanthropy and Philanthropists in Australian Colonial History 26/07/2025 available at https://wp.me/p4YcFE-BL

[1] Fourth Annual Report of the Sussex Street Ragged and Industrial School, 1864.

[2] Paul F Cooper Thomas Walker (1804-1886) Businessman, Banker and Philanthropist 21 May 2016. Available at https://phinaucohi.wordpress.com/2016/05/21/thomas-walker-1804-1886-businessman-banker-and-philanthropist

[3] Paul F CooperMary Roberts nee Muckle (1804-1885), Property holder, Philanthropist and Publican. Philanthropy and Philanthropists in Australian Colonial History, August 27, 2014. Available at https://phinaucohi.wordpress.com/2014/08/27/mary-roberts-nee-muckle-1804-1885/

[4] The Sydney Gazette and New South Wales Advertiser, June 26, 1813. Hereafter the SGNSWA.

[5] SGNSWA, January 22, 1814.

[6] SGNSWA, May 8, 1819.

[7] SGNSWA, June 28, 1817.

[8] SGNSWA, June 6, 1818.

[9] Messrs Jaques and Scott did so in 1819. SGNSWA, December 18, 1819.

[10] SGNSWA, October 9, 1823.

[11] SGNSWA, September 27, 1826.

[12] SGNSWA, February 3, 1821.

[13] Paul F Cooper. Charles Nightingale (1795-1860), Edward Ramsay (1818-1894), Arthur Balbirnie (1815-1891) and James Druce (1829-1891) Charity Collectors. Philanthropy and Philanthropists in Australian Colonial History, June 9, 2016. Available at https://phinaucohi.wordpress.com/2015/07/12/charles-nightingale-1795-1860-edward-ramsay-1818-1894-arthur-balbirnie-1815-1891-and-james-druce-1829-1891/

[14] SMH, May 3, 1897, 6.

[15] Newcastle Morning Herald and Miners’ Advocate (NSW), 15 March 1890, 2.

[16] SMH, December 12, 1896, 15.

[17] The Australian Star (Sydney), 26 August 1896, 5.

[18] The Australian Star (Sydney), 23 October 1891, 5.

[19] The Australian Star (Sydney), 20 August 1896, 2.

[20] The Australian Star (Sydney), 26 August 1896, 5.

[21] The Australian Star (Sydney), 5 September 1896, 7.

[22] The Australian Star (Sydney), 26 August 1896, 5.

[23] The Australian Star (Sydney), 5 September 1896, 7.

[24] Daily Telegraph, (Sydney), 27 August 1896, 2.

[25] SMH, 27 August 1896, 3.

[26] The Australian Star (Sydney), 5 September 1896, 7.

[27] SMH, 20 August 1896, 3.

[28] SMH, 27 August 1896, 3.