Catherine (Kate) Gent nee Danne (1835-1899), Teacher and Vocational Philanthropist

A ‘Mr and Miss Danne’ were involved in the Ragged Schools of Sydney as part of a philanthropic attempt to assist the children of the poorest to gain some education and improve their situation in life. They were what might be termed ‘vocational philanthropists’ for they did not give financial support, other than by forgoing more lucrative employment, nor did they serve as committee members overseeing the work. Rather, they were employed by the committee to interface with the poor, assisting the parents and teaching their children, and the level of Miss Danne’s commitment and sacrifice meant that this employment was her vocation. They were both associated with the Ragged School as teachers and Miss Danne was appointed to the paid staff in October 1860[1] to teach the girls and to support Henry B Lee, the one paid male teacher.[2] With Lee’s departure around May 1861, a Mr Danne was appointed to replace him.[3] His salary was 30 shillings per week, while with his appointment, the salary of Miss Danne was increased from 30 shillings to 40 shillings per week.

So who were ‘Mr and Miss Danne’ of the Ragged School? The answer to this question is not immediately apparent as contemporary accounts refer to them simply as ‘Mr and Miss Danne’. The Danne Family, consisting of William Danne (1807-1870) and his wife Agnes nee O’Donnell (1810-1866) along with their four daughters Rebecca (1825-?), Catherine[4] (1835-1899), Margaret (1839-1897) and Agnes Ann (1844-1941), and possibly their son Richard Vallancy (1846-1904), arrived in Sydney aboard the Tudor on August 17, 1860, as immigrants from Ireland. John Thomas (1834-1907), a second son, arrived around 1863.[5]

‘Who was the Mr Danne of the Ragged School?’ Eureka Henrich identifies ‘Mr Danne’ as the father of Miss Danne.[6] Miss Danne’s father was indeed associated with the Ragged School, but her father William was only a charity collector for the Ragged School from 1861 to 1862 and he was not a teacher.[7] When he joined the Post Office in May 1862 as a clerk, William relinquished his post as collector and a Mr Peterson was appointed in his place.[8] The Mr Danne of the Ragged School, however, is clearly identified in a report as Miss Danne’s brother[9] and is noted in the 1865 Sands Directory for the Ragged School as ‘R.V. Danne’. This stands for ‘Richard Vallancy Danne’ who was, when first employed, about 16 years of age.[10] Richard continued his work at the Ragged School until the end of 1865.[11]

‘Who was the ‘Miss Danne’ of the Ragged School?’ This is a more difficult question to answer as she is simply and continually referred to as ‘Miss Danne’. A close examination of the records of the Ragged School, however, leads to the conclusion that Miss Danne had to be Catherine Danne, known as ‘Kate’.

Miss Danne began work in the Ragged School in October 1860, not long after the arrival of the Danne family in the colony. In May 1862, it was reported that a residence had been found for Mr and Miss Danne in the ‘immediate neighbourhood’ of the school.[12] In 1863, Kate Danne is known to be living in 408 Kent Street which was a three minute walk to 183 Sussex Street where the Ragged School was located.[13] In June 1864, Miss Danne was presented with a gold watch in recognition of her work at the Ragged School and later that year Kate Danne gave £3 to a fund to celebrate the Jubilee of the Wesleyan Church ‘as a thank offering for mercies received in a ragged school’.[14] Miss Danne’s last mention in connection with the Ragged School is in the annual report of July 1866, with no mention of her as Miss Danne in 1867 or thereafter.

In 1867, Kate Danne married William Henry Gent.[15] In November 1867, Edward Joy, the secretary of the Ragged School Committee, indicated he could not continue in this role and so he submitted a statement of the finances of the School. This statement indicated that Mrs Gent was owed £6 for work done at the school in the month of November 1867.[16] In June 1882 the Secretary of the Ragged School drew up a table of salaries of employees and their dates of appointment. Mrs Gent was at this time being paid £78 per annum and her date of appointment was listed as 1860.[17] Miss Danne and Mrs Gent are clearly one and the same person which makes the Miss Danne of the Ragged School, Miss Kate Danne.

In 1868, William Gent, Kate’s husband, applied for a job at the Ragged School and was appointed to work as a teacher.[18] Over the next five years, Kate gave birth to three children but seems to have continued her work at the school without any break.[19] Kate gave birth in 1868 to their first child, Ernest F Gent,[20] in 1870, to a daughter, Mary Agnes[21] and in 1872, to her third child, Henry.[22] There is no indication in the Ragged School minutes up until 1877 of Kate taking any time away from teaching.[23] It would appear that she balanced, or perhaps had to balance, the nineteenth century roles of wife, mother and wage earner. In 1877, William Gent wrote a letter of resignation from his position and in a separate letter Kate also resigned from her position. Curiously, the Ragged School Committee offered to Kate ‘that should she desire to remain for a short period as teacher they would pay her 30/- a week’.[24] While William is replaced as a teacher Kate is not and she appears to have stayed on with her resignation never taking effect. Later that year, she wrote to the committee seeking an increase in salary which was refused due to a shortage of funds.[25] In 1880, she wrote to the Sydney Morning Herald to give thanks to donors for clothing and signed the letter, ‘Yours gratefully Kate Gent, Kent Street Ragged Schools’,[26] and in 1881, she attempted to organize a reunion of Ragged School scholars.[27] By 1887, her daughter Mary became a teaching assistant in the school and continued in this role until 1889.[28] In 1889, the closing of Kent Street Ragged School was reported and it mentioned that Mrs Gent, who had worked for the Ragged School for over 20 years, was moving to the new Ragged School at Brisbane Street.[29] Kate continued to work at this Ragged School until her retirement.[30]

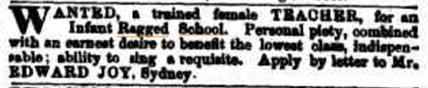

Kate Gent nee Danne was involved with the Ragged School from the time of her arrival in the colony of NSW in 1860, through her period of rearing three children and up until 1891, a few years before her death in 1899. She served and supported successively the Sussex Street, Kent Street and Brisbane Street Schools and was a devout Wesleyan who, in concert with Edward Joy and the philosophy of the Ragged School, believed in the importance of the Bible in educating children. Henrich suggests that single women teachers, such as Miss Danne, ‘were not required to have any teaching qualifications, as the role was seen as primarily missionary rather than educational’.[31] While it is true there was a strong missional emphasis, the case ought not be overstated by making a clear distinction between the Ragged Schools’ missionary and educational function as such a distinction was not clear-cut in the mind of Edward Joy, the founder of the schools and the employer of Kate. We do not know the actual teaching qualifications of the paid female teachers, but we do know of Joy’s aspiration for qualified teachers. When Joy was advertising for a teacher for the Ragged School in the Sydney Morning Herald, June 25, 1862, he advertised as follows:

The advertisement required four things of a female teacher: to be a trained teacher, have personal piety and an earnest desire to benefit the lowest class, and to have the ability to sing. Clearly his aspiration for the teacher was both educational and missional and this aspiration continued in advertisements for teachers at least until the end of the century.[32]

In 1869, the school was visited by J Huffer, Inspector of Schools under the Council for Education, and he reported that

in the Sussex street school I found Mr and Mrs Gent engaged in their work with much earnestness, and from the examination made, I am able to report that their success, under the peculiar circumstances and organisation of the school, is, on the whole, satisfactory. Mrs Gent possesses many excellent qualifications for the work in which she is engaged; and had a proper supply of suitable books and school materials been furnished for the use of the pupils, much higher results would I am convinced, have been shown.[33]

It is clear that whatever formal qualifications Kate did or did not possess, she was doing a good job of teaching the type of students who came to the Ragged School.

The committee reported that Kate Danne not only taught classes, but had been indefatigable in visiting the scholars in their own homes and in doing so was endeavoring to reform the parents, for she was aware that the good done in the school could be undone in the home.[34] With Edward Joy’s encouragement Miss Danne, reflecting Bayly’s book[35] which had so influenced Joy in commencing the Ragged School, set up a mother’s group where old clothes were cut up and remade, books read aloud and songs were sung. She also held a Sunday evening meeting at which the bible was read, hymns sung and prayers made. The Dannes became part of the community as the committee found accommodation for them in the neighbourhood. The provision of this accommodation allowed the Dannes to be near their work and to immerse themselves in the community to whom they ministered. They were accessible to parents and their advice was constantly sought, and it was also hoped that Miss Danne might be able to take a few girls to reside with them to prepare and train them for domestic situations.[36]

Kate kept a journal of her daily activities as part of being accountable to the committee for her time.[37] From this journal the committee took extracts to advise its supporters on the progress and the challenges of the work. Karskens notes that such committee reports were often ‘aimed at fascinating and horrifying readers, or persuading them to renew subscriptions’ and that they drew on pre-existing cultural assumptions and literary devices.[38] On the basis of archaeological discoveries at the Rocks, she has argued that in the picture of the families among whom Kate worked, as presented in reports such as those of the Ragged Schools, was a distortion and an exaggeration:

Difference, poverty, poor housing, social and urban problems which did exist, were drawn out, magnified, demonised, while the obvious day-to-day fabric, the homes, families, communities and the things with which most lives were constructed and defined, remain largely invisible, unremarked.[39]

Karskens has made an excellent point worth taking into account when constructing, as she does, an overall picture of the populations of the ‘slums’. While acknowledging this and reading Kate’s journal entries in this light, we must not devalue and dismiss their content.

In deconstructing Kate Danne’s reported comments, the context of the comments needs to be considered. It is certainly true that the picture presented by the excerpts from Kate’s journals are not the full and complete story of the areas in which she worked. Her task was not to visit the whole community, however, but only those who would benefit from the ministry of the Ragged School and this explicitly excluded, as the discussion on the name of the schools indicated,[40] the ‘more affluent’ poor who could afford to pay the fees for schooling their children. Kate would have had little or no control over what appeared in the committee reports, and the excerpts that were chosen from her journal were selected to present a picture that would assist in gaining and maintaining funding. The sympathy of the Christian public, for the work was always presented as a Christian duty, was imperative for without it the work would cease as there was no government funding to carry it out.[41] It should also be noted that the only access we have to Kate’s journal is from the very few excerpts that were selected, probably by Edward Joy. We do not know the full range of Kate’s observations and whether or not she made comments on things such as ‘the obvious day-to-day fabric, the homes, families, communities’ that Karskens sees as missing from contemporary observations.

As a middle class Wesleyan Christian, schooled in the bible and its moral values and precepts, Kate viewed things from that perspective.[42] She would express what she saw in words and images that had a biblical content linked to them like ‘fallen, depraved and drunken’ and ‘den’, which sound extreme to the modern ear that does not share the Christian world view Kate possessed. A number of times she expressed shock at what she had seen and her journaling was probably, in part, cathartic in her coming to terms with what she experienced.

Yes, it is true, I do see sorrowful sights. Had I seen such a couple of years ago they would have killed me, but by degrees my Heavenly Father has gently prepared me for this work. As I walk along I often think of what the Son of God must have felt while journeying here below, when he not only saw the surface but down into the depths – not only saw the sin, but felt it.[43]

Though the citations from Kate’s journal were ‘fascinating and horrifying’, it does not follow that the particular cases she cites were not true, or that her descriptions were not a realistic and truthful representation and a part of the ‘difference, poverty, poor housing, social and urban problems that did exist’.[44] Her depictions have a ring of truth about them, such as the following:

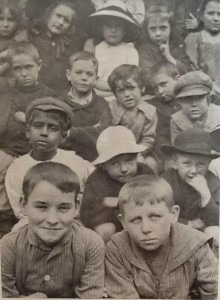

Two boys came to our school, one nine and the other four years of age. They were homeless, they slept in casks or cases, or wherever they could find shelter, and lived upon the charity of the poor.[45] Their mother was in gaol; their father had deserted them. They were wild, untaught, unclad, suspicious, and whimsical.[46]

That the boys were that age, homeless and sleeping rough and dependant on charity, and that their mother was in gaol and their father had deserted them, should be taken as factual statements. That the boys are described by her as ‘wild, untaught, unclad, suspicious, and whimsical’ are perhaps value judgements, but given the situation of the boys they are judgements which are entirely believable. Similarly, apart from suggesting Kate was making it up, it seems difficult to evade the conclusion that she often encountered domestic violence situations related to the abuse of alcohol:

Went to see another poor woman who had come one night to the school with a very black eye and bruised face, so much so she kept her face hidden all the time of the meeting. After it was over she called her husband, and both signed the pledge – their little daughter, who had brought them both to the meeting, standing near with a very pleased face.[47]

Something of Kate’s attitudes to her work and those among whom she laboured may be seen from this excerpt from her journal:

It is only wisdom from on high that can show anyone how to deal with this people. They will not be dictated to. Some ladies, visiting lately, have given offence by doing so. One must try to do them good without even seeming to do it. It is like dealing with insane people who do not know they are so, and they are treated in many instances as if sane. So these people must be spoken to, in many cases, as if they were not fallen, depraved and drunken. By respecting them you teach them to respect themselves. One of them said to me the other day, ‘Everyone laughed at me, mocked me as a drunken character, and told me I never should be anything else. You respected me, and gave me the first words of hope I ever heard from human lips’.[48]

While the analogy of the insane may lack modern sensitivity, it is clear that she sought to come alongside the community to commend her values, which she would have cherished for her own family, rather than seeking to impose them from the position of a social superior. Kate was not an outsider coming into the community, like some of the middle class lady visitors, for she lived there and spent a good proportion of her adult lifetime renting accommodation in Kent and Clarence Streets in the vicinity of her work at the Sussex, Kent and Brisbane Street Schools. She said, ‘My time, from morning to night, has been almost every moment occupied, for scarcely a day passes during which one or more poor men or women do not call to tell me some tale of sorrow.’[49] The Ragged School committee was convinced that in regard to the parents of the children ‘a great advantage exists from her having fixed her residence in their immediate neighbourhood’.[50]

Throughout her life, Kate not only worked for the Ragged School but she was, three years after the birth of her last child, constantly advertising herself as a private teacher. Her advertisements over the years always used her place of residence as the venue,[51] but the sought after clientele changed. She advertised ‘Evening classes for the children of the people’,[52] ‘Music – one shilling a lesson, wax flowers and every branch’,[53] ‘Afternoon Tuition – Piano, Harmonium, Wax Flowers’,[54] ‘Mrs Gent’s Evening Classes. English, French, music, wax flowers, drawing, painting’,[55] ‘Lessons given to LADIES of NEGLECTED EDUCATION in every branch’,[56] ‘A NIGHT SCHOOL for Boys, Reading, writing, arithmetic, also music lessons’.[57] It would seem that the remuneration of the Ragged School needed to be supplemented by other income. “Samaritan” commented on the self-denying nature of the workers at the Ragged School and observed that Mrs Gent, in being a schoolmistress for over 20 years, had done so ‘at great pecuniary loss to herself’.[58]

It appears that Kate’s personal life was also difficult and that she and her husband, sometime after 1883, became estranged. At one point, a magistrate issued an order for William to be arrested for failing to obey a ‘magisterial order for the support of his wife’.[59] In 1903, Kate’s daughter, Mary Agnes Gent, who had become an accomplished music teacher,[60] married and in the report of her wedding she is described only as the daughter of the late Mrs Kate Gent.[61] No mention is made of her father William who was still alive and only died the following year.[62] Though Kate’s personal circumstances may have been difficult, she managed to save enough money to purchase her own home. In 1888, she purchased Roydon Villa, 38 Nowranie Street, Summer Hill, for £495.[63] It was a four-roomed brick cottage with a kitchen, wash house and detached wooden schoolroom.[64] Kate soon advertised her new location where she was conducting, probably in cooperation with her daughter, a Ladies School. Despite her move to the suburbs, Kate continued her work with the Ragged School and was principal of the Brisbane Street School until 1891.[65]

Around the time of her move to Summer Hill, Kate became involved with ‘The Dawn Club’, associated with the newspaper edited by Louisa Lawson.[66] The Dawn Club was a group of ladies who met for ‘mutual development, for mutual aid, and for the consideration and forwarding of various questions of importance to the sex’.[67] Kate spoke at the Club’s meetings and she contributed articles to The Dawn newspaper, both seeking support for and reporting on the work of the Ragged

School. She showed something of her Christian motivation for the work when reminding the editor and her readers that, ‘We can only show our love to the Father, by being kind to His children, and this we will do.’[68] After over 30 years of work with the Ragged Schools, she was still affected by the sights she saw. Describing the living conditions of several large families in a leaking condemned house she said,

Think of human beings living thus; think of children being born and reared in places like this, without even a thought of privacy, decency, or purity and then you can have an idea of our trials in this work. Really, dear friend, it is an awfully trying life, to see and feel all this and much more. But I must not complain. The boys and girls frequently turn out well, and this makes up to us for all our troubles.[69]

Her comments on other difficulties which the work of the Ragged School encountered reflected her belief, espoused throughout her life, that the abuse of alcohol was a major problem:

Generally speaking, the children are healthy and happy, so a little goes a long way with them. Xmas is not a good time for them, because the elders spend all the available money on drink and the ‘wee ones’ are ill-used, or neglected in consequence.[70]

One of the boys sells papers in the streets, and his father (a drunken loafer) goes around after him and takes the money from him, spends it in the public house, and then goes ‘home’ at night to beat his children. This is a common case.[71]

Kate’s solution was to encourage her readers to support the ‘Temperance and Social Purity’ movements as much as they could.[72] In her advocacy of temperance she appealed to women first, ‘because they are the greatest sufferers through the drunkenness of the men’. She asked what pleasure women got from the drinking of men? Her sardonic answer, no doubt coloured by her extensive experience in conversing with women who suffered from the effects of their husband’s alcohol abuse, was:

Does she enjoy sitting over the fire waiting to let in a drunken brute. Does she enjoy weeping her sight and her heart away, when she sees all her dreams of happiness in her married life, cruelly dispelled.

Well, please tell me what part of it brings pleasure to her- perhaps her black eyes. Does she take pleasure in her children? She cannot, because the unspoken dread is for ever there – “They may live to be like their father.”[73]

Temperance and total abstinence advocates, such as Kate, saw alcohol as the problem. Such a diagnosis to modern ears is facile, for the root cause lay much deeper with those issues that led men and women to begin drinking in order to make their lives more bearable. Nevertheless, excessive alcohol consumption did cause enormous problems within the society in which she worked. In her limited way, she did what she could to assist the children of that society so they could have a better future.

On one occasion, Kate also spoke at a meeting of The Dawn Club on the ‘mission of thinking and progressive women’, and a report of her address said she

quoted Carlyle’s adjuration, “if you have any work to do in God’s name, do it!” and pointed out that the mission of those who perceive the sorrows of the world and hope to effect some mitigation is to act at once and not be content with talking, to find out what can be done to lighten the burdens of all sorrowing of suffering sisters.[74]

In her life time, Kate had done as she advocated, seeking to assist children and their families to have a better life and a better future. In her address she also remarked, perhaps with some reflection on her own life, that

women who live in comfort, with good husbands to take care of them have not even a remote idea of the sufferings numbers of their own sex are undergoing, but that those who work alone in less easy circumstances see so much pain and wretchedness on all sides that all creation seems to be groaning.[75]

At the conclusion of her statement, as she often did, Kate was alluding to biblical teaching. The verse she was paraphrasing is from Romans chapter 8 verse 22, and the context exhorts readers that the sufferings of this present time are not worthy to be compared with the glory which shall in the future be revealed. It is a statement of hope and faith in God that he will in the end deliver his people from the present corruption and grant them the glorious liberty of the children of God. It was such a Christian hope and faith that sustained Kate in her work.

Kate Gent was one of a number of dedicated women who gave a lifetime of service to the work of the Ragged Schools.[76] In doing so they gave hope and opportunity to numerous children who otherwise would not have received an education. Kate and her fellow teachers deserve to be remembered and their contribution to society acknowledged.

Dr Paul F Cooper, Research Fellow, Christ College, Sydney.

The appropriate way to cite this article is as follows:

Paul F Cooper. Catherine (Kate) Gent nee Danne (1835-1899), Teacher and Vocational Philanthropist. Philanthropy and Philanthropists in Australian Colonial History, September 1, 2015. Available at https://phinaucohi.wordpress.com/2015/09/01/catherine-kate-gent-nee-danne-1835-1899-2/

[1] Empire, May 14, 1861, SMH, May 14, 1861.

[2] Lee was the editor of the The Australian Home Companion and Band of Hope Journal.

[3] Empire, May 14, 1861, SMH, May 14, 1861. Danne was appointed at a meeting of the Ragged School Committee in May 1861. Ragged School Minutes, May 27, 1861.

[4] Recorded and spelt variously: Catherine or Kathleen, Katherine and shortened to Kate.

[5] John Thomas Danne Death Certificate 11039 NSW Registry Births Deaths and Marriages would give a date around 1866 but he was in the colony by June 1863, Empire, June 13, 1863. RV Danne is not listed with his sisters and parents on arrival in 1860 but it is assumed that for some reason his name was omitted as he is in the colony by 1861.

[6] Eureka Henrich, ‘Ragged Schools in Sydney’, Sydney Journal, Vol 4, No 1 (2013), 55.

[7] The Collector is identified as Wm Danne in a list of payments. Ragged School Minutes, July 1, 1861.

[8] SMH, June 1861; June 26, 1862 and New South Wales Government Gazette, May 2, 1862. Ragged School Minutes, July 28, 1862.

[9] SMH, April 11, 1862, Goulburn Herald, March 23, 1864.

[10] Sands Directories for 1865 and 1866. Miss Danne’s other bother John Thomas Danne, a grocer, was a Sunday school teacher at the York Street Wesleyan church. Empire, 13 June 13, 1863.

[11] SMH, December 6, 1865 advertised for a Master for Sussex Street School. Richard would in 1866 become a Wesleyan preacher and later a minister and later still he went to the United States to complete his studies to become a doctor.

[12] SMH, May 31, 1862.

[13] City of Sydney Assessment Book for 1863 Brisbane Ward, Sands Directory for 1863.

[14] SMH, November 21, 1864.

[15] NSW Births, Deaths and Marriages. Marriage Certificate 434/1867.

[16] Ragged School Minutes, November 15, 1867.

[17] Ragged School Minutes, June 17, 1882.

[18] Ragged School Minutes, March 30, 1868; July 10, 1868. As part of the austerity measures the Industrial school was closed and the teacher in charge of the Industrial school discharged. Mr Gent was employed as a teacher at this time and was employed at a much lower salary than the previous teacher. SMH, July 30, 1868.

[19] Requests for leave from teaching duties required permission and were usually recorded in the minutes. There is no mention of Kate every having time away from her duties until 1877 when she and her husband submit their resignations from the school. Ragged School Minutes, February 23, 1887.

[20] NSW Births, Deaths and Marriages. Birth Certificate 770/1868.

[21] NSW Births, Deaths and Marriages. Birth Certificate 1149/1870.

[22] NSW Births, Deaths and Marriages. Birth Certificate 541/1872.

[23] Kate is mentioned in the annual report of 1871, indicating she is still involved with the Ragged School.

[24] Ragged School Minutes, February 23, 1877.

[25] Ragged School Minutes, August 20, 1877.

[26] SMH, October 30, 1880.

[27] SMH, June 7, 1881.

[28] Ragged School Minutes, May 31, 1887; March 18, 1889.

[29] The Dawn (Sydney, NSW), November 5, 1890. The notice said the new work was in Bourke Street which was in error as the school had been moved to Brisbane Street.

[30] Sands Directory, 1892. Her letter of resignation was received at the December 1891 meeting of the Ragged School Committee. Ragged School Minutes, December 16, 1891.

[31] Eureka Henrich, ‘Ragged Schools’, 56.

[32] Isabella Brown who was appointed in charge of the Waterloo School in 1886 and had worked at Glebe as an assistant prior to that was an English-trained teacher. Evening News, January 12, 1886, SMH, February 13, 1932. In 1892 when a teacher was again required for the Waterloo School the advertisement stipulated ‘must have had some training as a teacher. SMH, January 18, 1892. Again in 1898 ‘a thoroughly competent teacher’ was required. SMH, February 11, 1898.

[33] Empire, August 17, 1869.

[34] SMH, May 31, 1862.

[35] This book was Mary Bayly, Ragged Homes and how to mend them. (London, Nisbet & Co, 1860) and it was dedicated to Lord Shaftesbury. It must have been around late 1859 that Joy read the newspaper account. The publication date of the book is 1860 but it was available in Melbourne at least from October 1859. Argus, October 15, 1859.

[36] SMH, May 31, 1862.

[37] It was a common practice of such charities to require this. Another example of this was the requirement of the Sydney City Mission for its missionaries to keep journals.

[38] Grace Karskens, Small things, big pictures: new perspectives from the archaeology of Sydney’s Rocks neighbourhood. http://faculty.washington.edu/plape/citiesaut11/readings/Karskens_2001_Small_things_big_pictures.pdf , 81 [accessed 30/11/2014]

[39] Grace Karskens, Small things, big pictures, 81.

[40] See Edward Joy (1816-1898) Pastoralist and Ragged School Philanthropist (add link)

[41] At various times such funding was considered but the Ragged Schools were resistant to the idea in order to preserve their independence and ability to maintain a Christian ministry aspect to the work.

[42] This is not to say that Kate did not also have a set of values that reflected her middle class background rather than any specific biblical precept or injunction.

[43] SMH, July 2, 1863.

[44] Grace Karskens, Small things, big pictures, 81.

[45] Is the ‘charity of the poor’ an objective or a subjective genitive? Is it the “charity given to the poor” (objective genitive) or the “charity given by the poor” (subjective genitive)? If the latter, it confirms evidence from other sources of the generosity of the poor towards their own and shows that Kate observed this feature of the life of the poor.

[46] SMH, May 14, 1861.

[47] SMH, July 2, 1863.

[48] Empire, July 2, 1863.

[49] SMH, July 2, 1863.

[50] Empire, July 2, 1863.

[51] Variously 280 Kent Street, 280 Clarence Street, 339 Harris Street Ultimo, ‘Roydon’ Nowramie Street Summer Hill.

[52] SMH, September 28, 1875.

[53] Evening News, May 26, 1876.

[54] SMH, September 11, 1879.

[55] SMH, May 30, 1879.

[56] Evening News, May 16, 1877.

[57] Evening News, February 1, 1884.

[58] SMH, September, 1880.

[59] NSW Police Gazette No 22 Wed June 2, 1886, 165.

[60] SMH, January 9, 1904.

[61] SMH, March 14, 1903.

[62] The Scone Advocate, September 9, 1904.

[63] SMH, March 17, 1888.

[64] SMH, February 19, 1887.

[65] 1892 Sands Directory. Ragged School Minutes, December 16, 1891.

[66] Louise Lawson (1848-1920), poet, writer, publisher, suffragist and feminist. She was the mother of the Australian poet and author Henry Lawson.

[67] The Dawn (Sydney, NSW), July 1, 1889.

[68] The Dawn (Sydney, NSW), June 1, 1891.

[69] The Dawn (Sydney, NSW), June 1, 1891.

[70] The Dawn (Sydney, NSW), January 5, 1891.

[71] The Dawn (Sydney, NSW), January 5, 1891.

[72] The Dawn (Sydney, NSW), January 5, 1891.

[73] The Dawn (Sydney, NSW), February 5, 1890.

[74] The Dawn (Sydney, NSW), July 1, 1889.

[75] The Dawn (Sydney, NSW), July 1, 1889.

[76] Others included the Bowie sisters; Louisa (1834-1884), Jessie (1836-1906), Kate (1838-1918) and Elizabeth (1840-1922) and Isabella Brown.

[…] The committee decided that a paid teacher was needed for the girls so, in October 1860, Miss Danne was appointed and just before the annual meeting in May 1861, a new master was required to replace […]

LikeLike

[…] female teachers at the Ragged School. Four other women who served for long periods were Kate Gent nee Danne (see article dedicated to her), Isabella Brown, Fanny Owen-Smith and Violet […]

LikeLike